With an illustrious lineup of ninety artworks by the likes of Raphael, Titian, Jacopo da Pontorno, Benvenuto Cellini, Agnolo Bronzino, and Francesco Salviati, Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1512–1570 examines how portraiture became a propaganda tool wielded by the ducal family to project power and cultural refinement.

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano), Italian, Monticelli 1503–1572, detail of Florence Laura Battiferri, ca. 1560. Oil on panel. 34 1/2 × 27 5/8 in. (87.5 × 70 cm).

When we think of visages that defined Renaissance art between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, we're drawn to depictions of mythological and biblical figures and unnamed dames. Yet these subjects were only part of the artists' exploration of the human form—there was also the thriving art form of portraiture, which sought to express universality through the depiction of specific individuals.

Domenico Compagni (called Domenico de’ Cammei), Cameo of Cosimo de’ Medici and Eleonora di Toledo, ca. 1574. Agate and gold. Diameter 1 1/2 in. (3.7 cm). Museo degli Argenti, Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

The main focus of the exhibition is the rule of Cosimo I, who reigned from 1537 to 1569. Thanks to his 1539 marriage to Eleonora di Toledo, daughter of a Spanish Viceroy, the Medici family developed a strong arts patronage program.

Portrait artists under Cosimo's rule and patronage worked within the principles of imitation and portrayal. The former concept is preoccupied with the reproduction of nature, while portrayal conveys intimate aspects of the sitter's identity through allegory and symbols.

Bronzino is a standout portraitist, celebrated for the way he combined likeness with allegory. His portraits were pictorial renditions of classical statues of mythological figures. In a 1537-39 portrait, Cosimo I appears as Orpheus, his pose and torso reminiscent of an ancient statue.

Likening Cosimo to Orpheus was a well-pondered choice. Just as Orpheus's music was able to appease even the most ferocious animal in the underworld, Cosimo's rule could both appease the Florentines that were hostile to the previous Medici rulers—ensuring the continuation of the Medici dynasty—and position Florence as a player that was now under the protection of the Hapsburgs.

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano), Italian, Monticelli 1503–1572 Florence, Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus, 1537–39. Oil on panel. 367/8 × 301/8 in. (93.7 × 76.4 cm).

Similarly, Bronzino's portrait of maritime hero Andrea Doria presents him as Neptune to celebrate his seafaring prowess against the Ottomans and Barbary corsairs.

Allegorical portraits, however, were not solely limited to rulers and their dynasties. Laura Battiferri, a celebrated female poet and friend of Bronzino, was depicted by the artist holding an open book displaying two sonnets by Petrarch and with a profile overtly echoing Dante's trademark aquiline nose.

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano), Italian, Monticelli 1503–1572, Florence Laura Battiferri, ca. 1560. Oil on panel. 34 1/2 × 27 5/8 in. (87.5 × 70 cm).

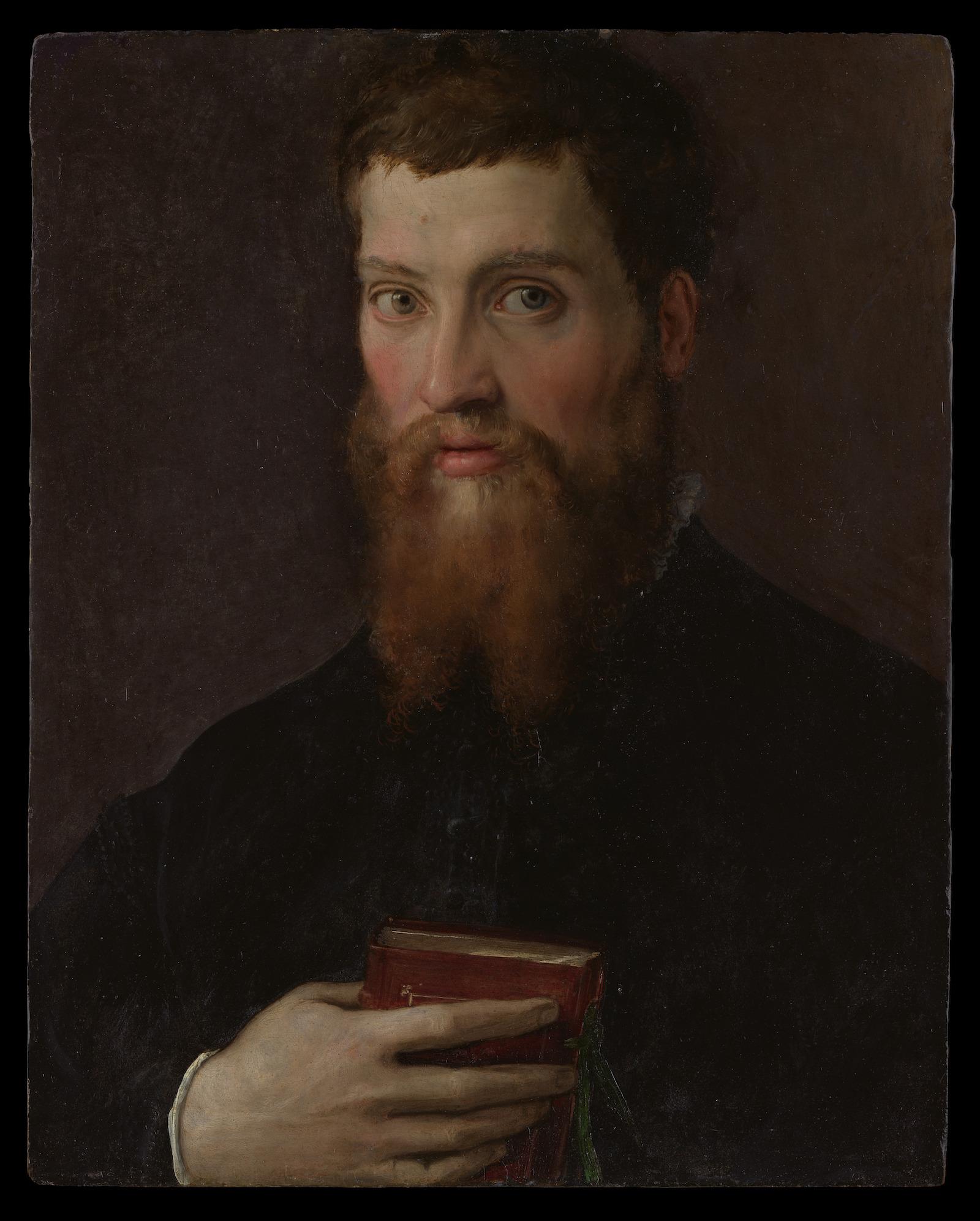

In contrast, the other painter who is amply featured in the exhibition, Francesco Salviati, had a more cosmopolitan style that drew from the influence of Rome and Venice. While less theatrical than Bronzino, Salviati’s style drew from Rome’s emphasis on fabric and texture, and from a Venetian taste for naturalism.

Salviati’s portrait of Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi (ca. 1541) combines an accurate rendition of textiles and flesh tones with psychological intensity. Meanwhile, the artist’s Portrait of a Man (1544–45) combines the pose from a Michelangelo sculpture of an idealized Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino with allegorical background elements such as the personification of the river Arno and the morning glory, which alludes to love poetry. The way Lorenzo de Medici holds his gloves, by contrast, is indicative of a courtly context.

In all, this exhibition demonstrates the artistic possibilities of portraiture. By going beyond the mere preoccupation with the imitation, figurative artists in the sixteenth century toy with erudition, allegory, and symbols to create artworks that lend themselves to several modes of interpretation.

Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1512–1570 will be on view at The Met until October 11, 2021.