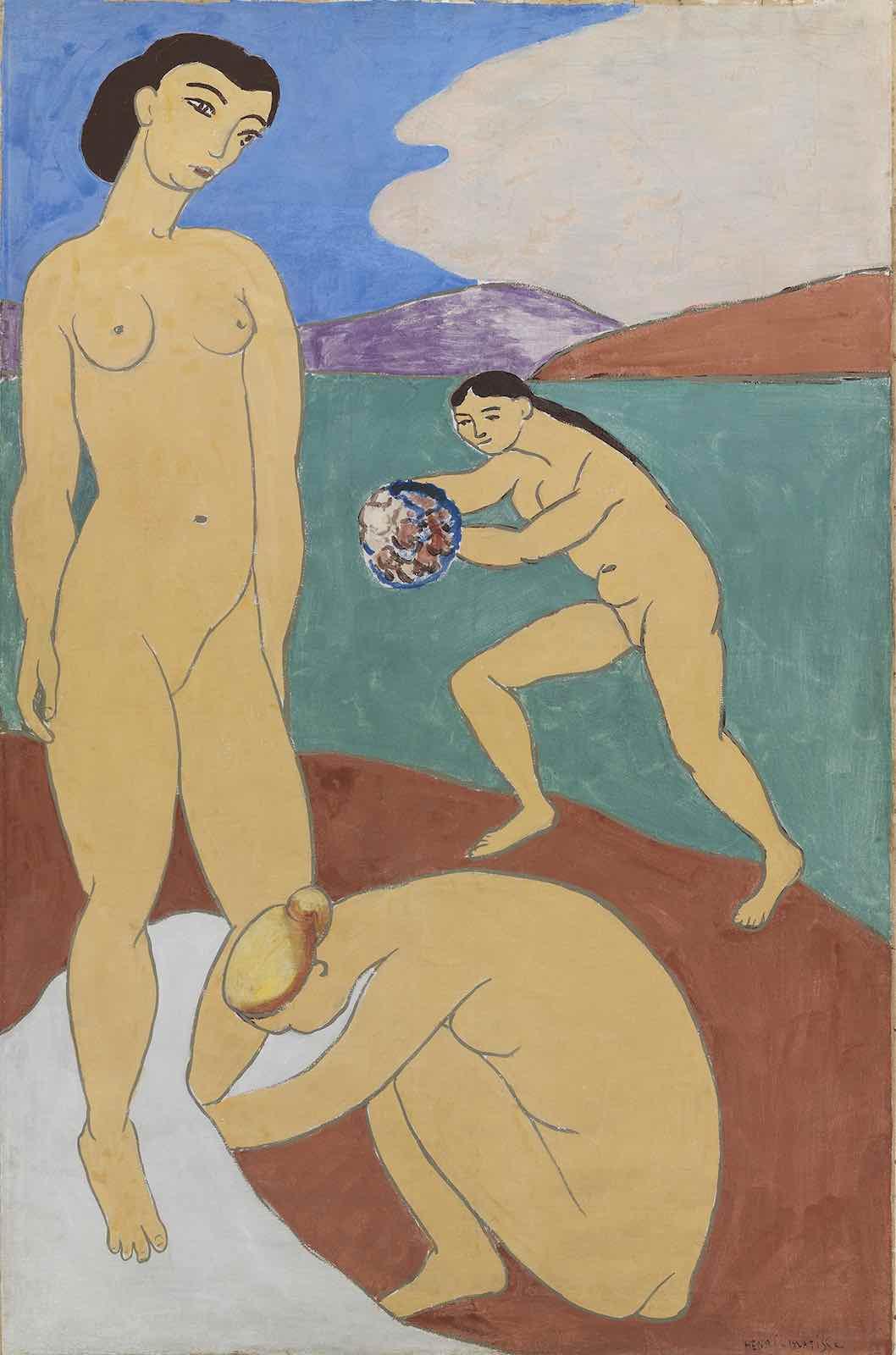

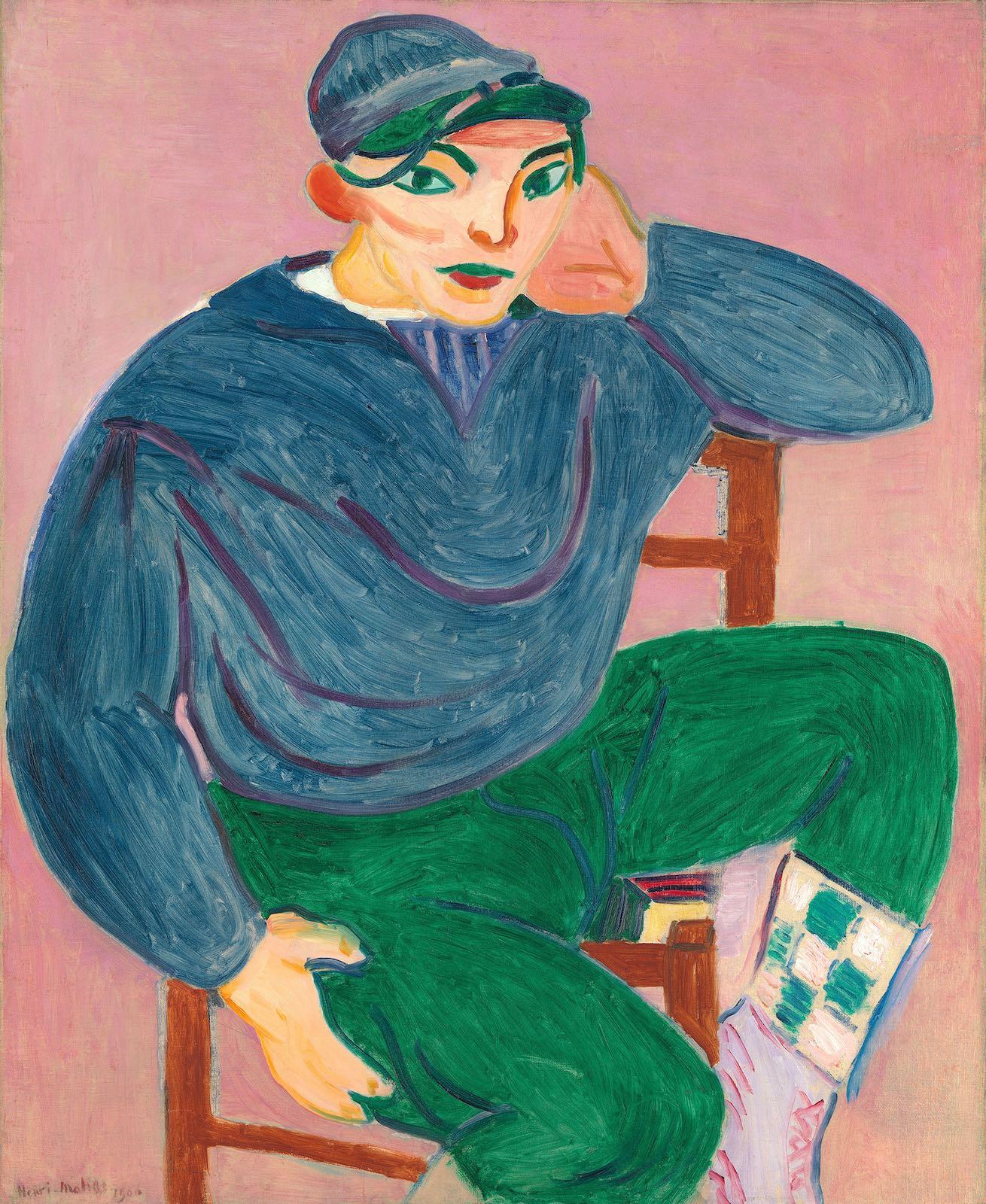

More pertinently, the exhibition displays the actual objects pictured within—career landmarks such as Young Sailor II (1906) and Le luxe (II) (1907). The show also reveals the unusual circumstances surrounding the canvas, which include its rejection by the patron who originally commissioned it (the Russian textile magnate Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin), the bewildered reaction to its public debut, and its tenure as the unlikely property of a British nightclub owner.

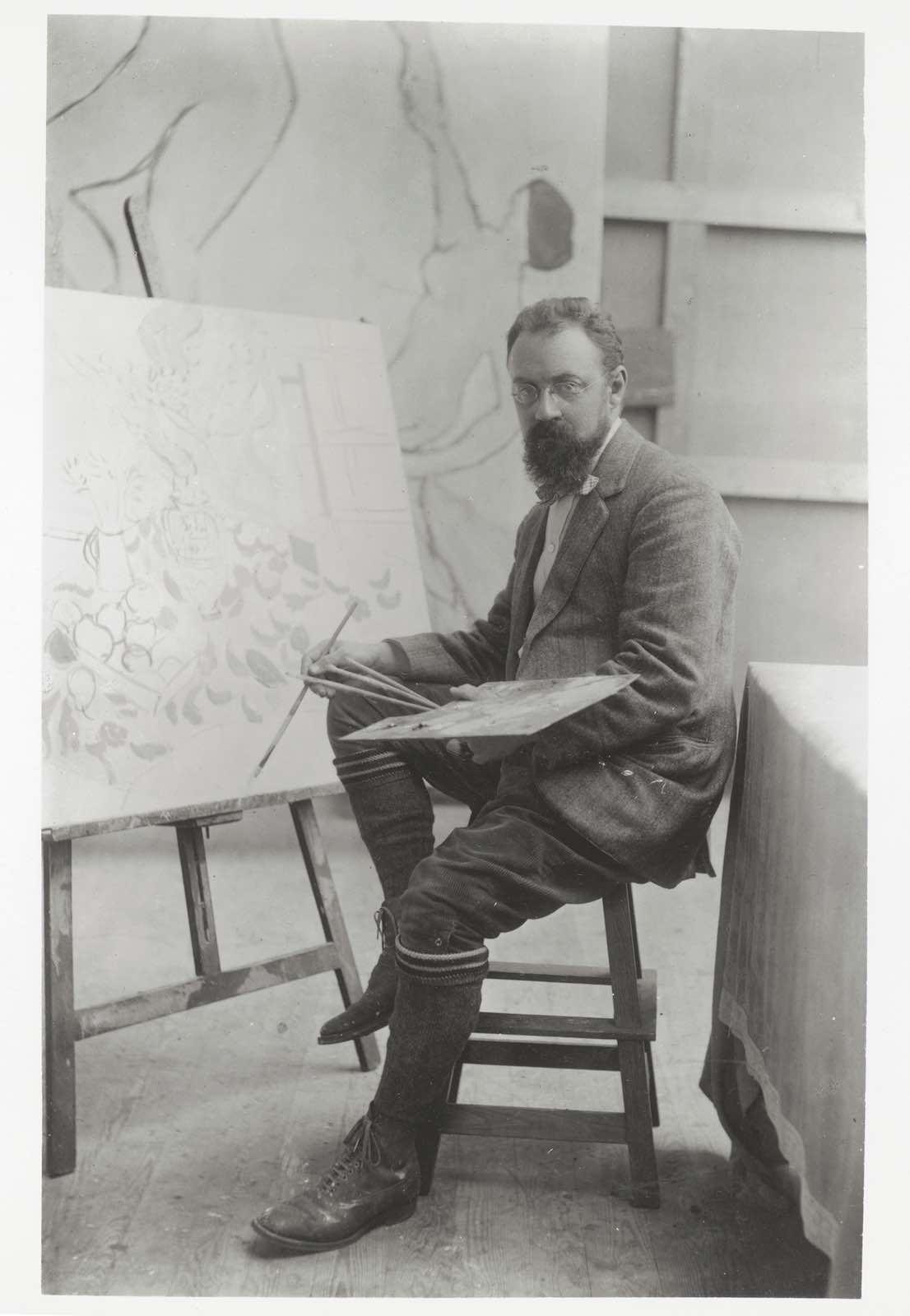

True to its title, the painting suffuses its subject in a field of deep carnelian while falling into the time-worn tradition of artists picturing their places of work. Such efforts offered a look into their art-making process and were effectively surrogate self-portraits. This takes on added significance for Matisse since he rarely portrayed himself, though he did depict his various studios throughout his practice.

Unlike similar paintings, however, The Red Studio presents little sense of the artist at work: Aside from an open box of blue crayons, there is no easel, palette, or brushes. Instead, there are completed works hanging on, or leaning against, the walls, along with objects and furnishings such as tables, stools, chairs, and a centrally located grandfather clock mysteriously devoid of hands.