Roman ruins are not normally found in the buildings of insurance companies. Yet in the Rome headquarters of Enpam—the National Insurance and Assistance Body for Doctors and Dentists—visitors descend below ground to the remains of an ancient luxury garden complex.

Opened to the public in November 2021 and located on Piazza Vittorio just south of Rome’s main railway station, the archaeological site and new museum, ‘Museo Ninfeo’, is the result of almost twenty years of work, the complexities of which involved constructing a carpark below the excavation and a multi-story building above it. It is an excellent example of how the sensitive preservation of archaeological remains in their original location and modern urban development are not mutually exclusive.

The displays of the Museo Ninfeo are incorporated into the archaeological area, meaning that visitors view objects found at the site as they walk over and through the ancient structures. The museum tells the history of this specific part of Rome from the fourth century BC, when it was still located outside of the Republican-era city, through to the ninth century AD, when it was largely abandoned after the end of antiquity.

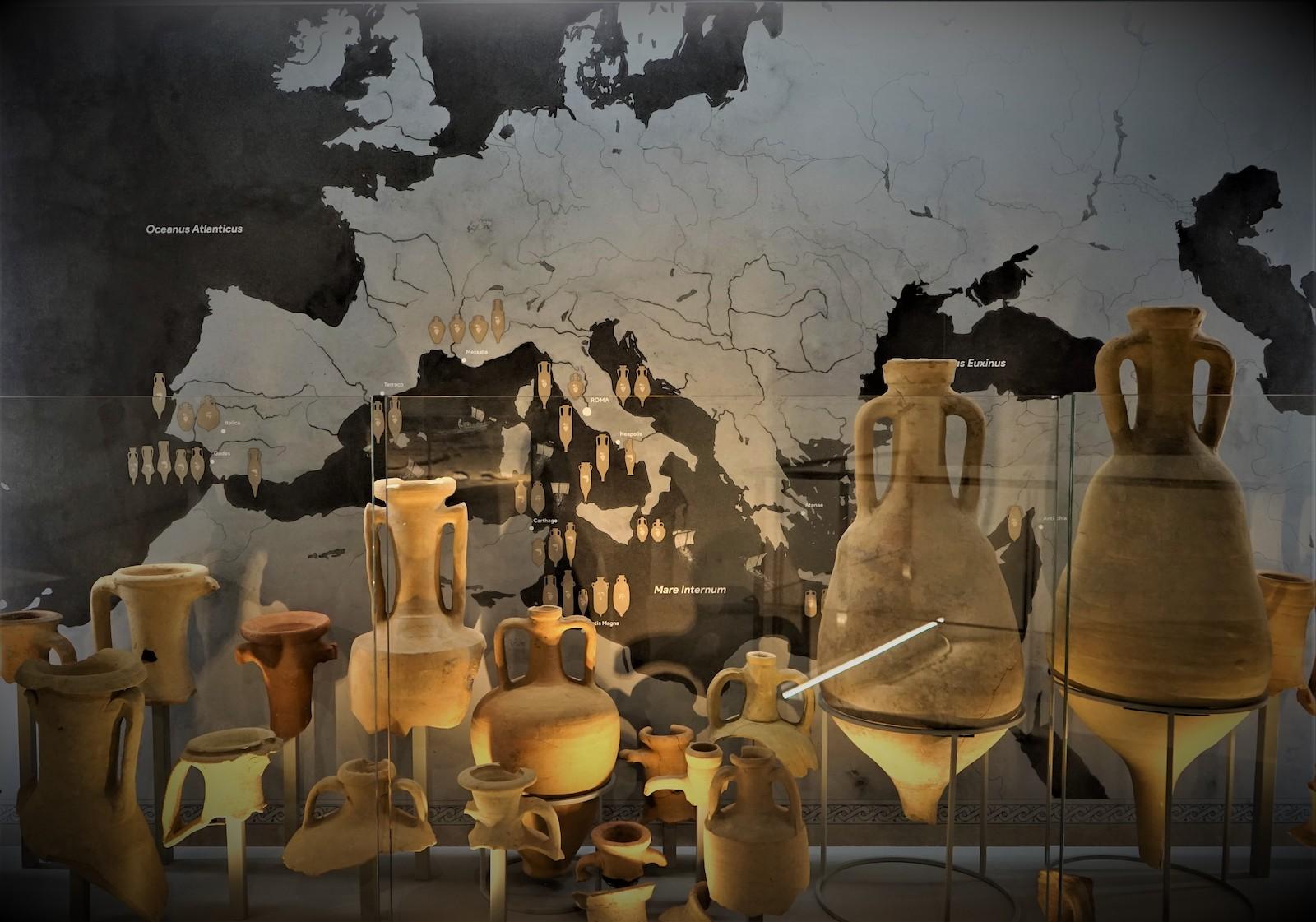

In its earliest historical phase, traces of plowing and planting show that the area was given over to agriculture. Then, in the second century BC, the ground was quarried for pozzolana, a type of volcanic sand which was used for producing concrete and was instrumental in the construction of Roman buildings.

Between the final years of the first century BC and the first decades of the first century AD, the senator Lucius Aelius Lamia transformed the terrain by covering over the quarries and laying out an expansive garden, subsequently known at the horti Lamiani. Although the Latin word ‘hortus’ is often translated as ‘garden’, these large estates were more akin to luxurious, private parks. Artfully landscaped and adorned with pavilions, water features, works of art, flowers, trees, and animals, horti were places for the wealthy of Rome to withdraw to and relax, away from the densely populated center. Lamia was not alone in creating such a space, and the gardens of other Roman aristocrats girdled the ancient city with artificial countryside.