Through a hole in the floor of a dining pavilion built by the later emperor Domitian, you descend an ancient marble staircase into a subterranean space where a series of rooms are arranged around what was once an open-air court. Along one wall runs the partial remains of an elaborate water feature designed in imitation of the stage backdrop of a Roman theatre, with regular niches flanked by miniature marble columns, in front of which fountains squirted water into the air. The floor of the court is paved in geometric patterns of colored marble brought from across the empire, while the walls and ceilings of the adjacent rooms still preserve frescos of figural scenes surrounded by elaborate borders and spiraling floral designs.

Painted ceiling in the Domus Aurea

For an emperor whose legacy was condemned after his death, Nero is surprisingly present in Rome today, especially now that his two palaces are again open to the public. Nero’s first residence was known as the Domus Transitoria (the House of the Passage), presumably because it connected existing imperial properties across the city. While most of this palace was either destroyed or now lies inaccessible beneath other structures, a decade-long restoration means that it is possible to visit part of it on the Palatine Hill for the first time in seventy years.

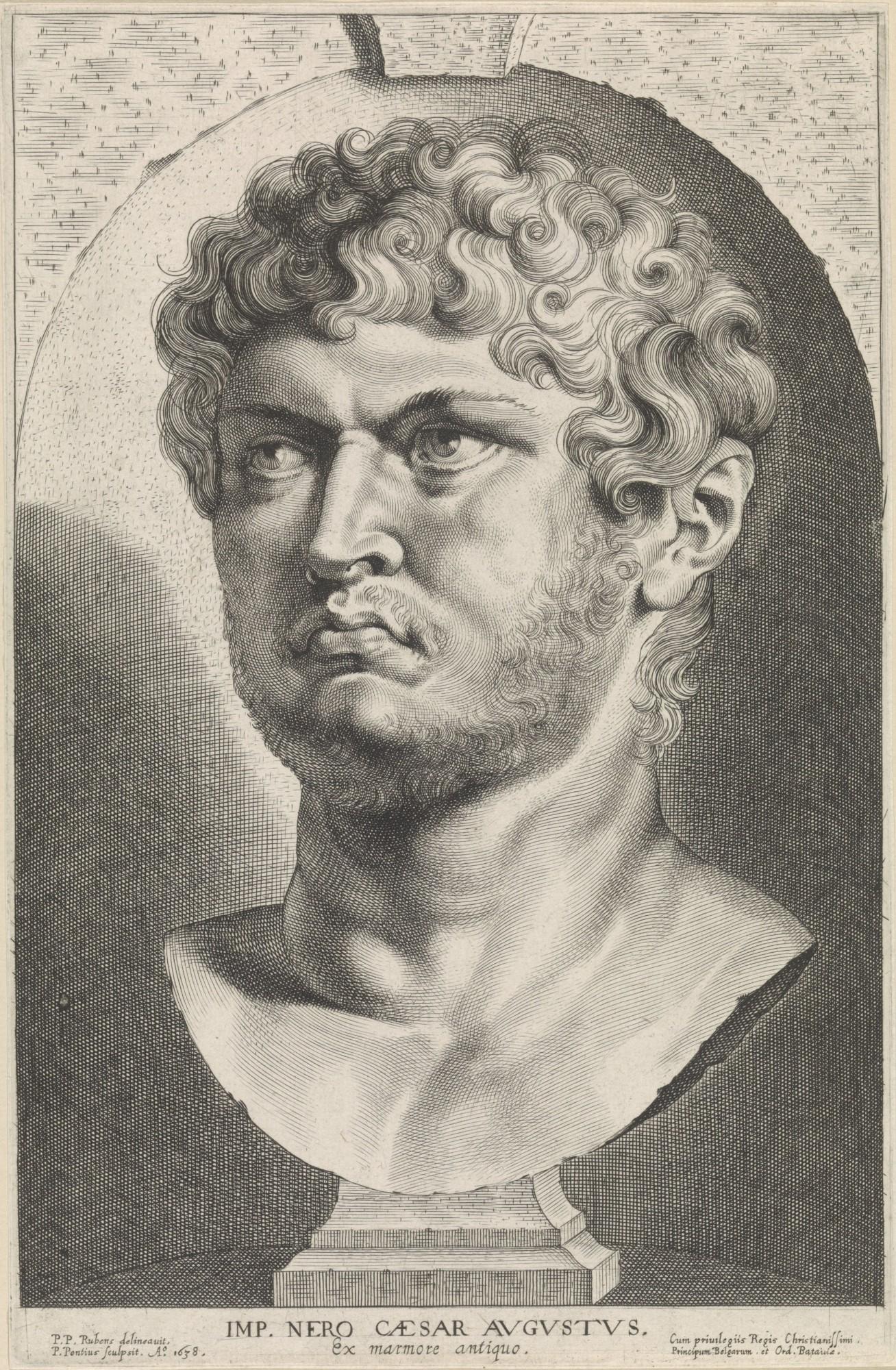

Paulus Pontius after Rubens, Bust of Nero, 1638.

Entrance to the Domus Transitoria

Away from the fountain court, is a less ornate space where the frescos on the wall are simple and in place of a marble floor are local stone slabs. Running around the outside is a drain that would have been covered by a series of fifty stone seats, each with a keyhole shape cut into them. This is an ancient latrine. Possibly one of several connected to the palace, its scale attests to the thousands of people who attended to the Imperial family.

Much of the Domus Transitoria burned in the Great Fire of AD 64, which Nero used as an opportunity to plan an even grander palace: the Domus Aurea (Golden House). Sprawling over nearly 200 acres, it was not a single building but a complex of pavilions interspersed between fields, vineyards, woods, and a vast artificial lake meant to imitate the sea.

Marble floor in the Domus Transitoria

After Nero’s death, his successors sought to distance themselves from such opulence. The lake was filled in and the Colosseum constructed in its place: a venue for public entertainment replacing a palace of private pleasures. Yet not all elements of the Domus Aurea were destroyed at once, and a substantial wing on the Esquiline Hill existed for another four decades until the Emperor Trajan chose it as the site of a huge public bath complex. Rather than demolish the Neronian buildings, Trajan constructed his baths on top of them. The concrete substructures of the baths were sunk through the rooms of the palace, which were then filled up with soil and forgotten for nearly 1400 years.

The rediscovery of the Domus Aurea under the ruins of the Baths of Trajan in the late 15th century was a key moment in the history of Western art. Artists including Filippino Lippi and Raphael, who left their names written on the ancient plaster, were lowered through holes in the ceilings. By torchlight they studied the frescos, brilliantly preserved by the dark, airless conditions. Inspired by this unprecedented insight into Roman painting, artists replicated and adapted the patterns in the churches and palaces of Renaissance Italy. This new style was labeled ‘grotesque’ after the grotto-like spaces in which its ancient models were found.

Fresco ceiling in the Domus Aurea

Today, the Golden House is again open to visitors, although the experience is quite different from that of those early artists. Underground, the spaces are difficult to comprehend and made more so by a number of the rooms of Nero’s palace being diagonally bisected by the enormous foundations of Trajan’s Baths above.

Octagonal room in the Domus Aurea

Yet the inventiveness of the architecture is still apparent. Most spectacular, although stripped bare of any decoration, is a suite of dining rooms arranged around an octagonal court. This central space is covered by an expansive concrete dome with a twenty-foot-wide circular opening (oculus) in the middle, allowing natural light to flood in. It has been suggested that this was the famous room known from the Roman biographer Suetonius, who describes a dining hall with a ceiling decorated to resemble the heavens and which constantly rotated day and night; although this identification is also disputed and it is unclear how such a contraption could have worked in the space.

The Domus Aurea presents serious conservation issues and the recent reopening comes in the wake of a partial collapse in 2010. In response, a new planting scheme has been introduced in the park that sits on top of the archaeology in order to lessen the weight of the topsoil. The damp conditions coupled with exposure to the air has also damaged or destroyed the frescos and the rich vibrancy of colors experienced by those who first entered the palace has long-since faded.

To make up for this, here and in the Domus Transitoria visitors can get a glimpse at the restored palaces through Virtual Reality. Donning the VR headsets, the visitor is immersed in the computer-generated world of Nero’s Rome. The technology recreates much of the lost decoration of the palaces (some of it necessarily conjectural) and helpfully strips away the substructure walls of the later buildings above the two palaces, making it possible to appreciate the size and appearance of the spaces as they originally were.

Last year the discovery of another room of the Domus Aurea was announced. Still filled almost entirely with soil, photographs show a vaulted ceiling decorated with frescos. Weighing conservation against archaeological interest, a decision will have to be made whether to excavate the rest of the room–whatever the outcome, the legacy of Nero looks set to stay in the public eye.