Milan Ingegneria’s motto ‘complex problems need simple solutions’ is evident in the elegance of the appearance of their design, but belies the sophistication of its construction. The floor is to be built using slats of sustainably-sourced Accoya wood, the arrangement of which matches the corridors and spaces underneath. These slats are rotational, allowing light and air into the substructures, controlling the humidity, and preventing damage to the archaeology. Parts of the floor will also retract, revealing the structures below and allowing for the surface to be used in creative ways. The danger of the accumulation of moisture is to be countered by the installation of a system for collecting rainwater, which then recycles it for use in the toilets.

The Colosseum today.

The Colosseum is to have a floor once more. In December 2020, a competition was announced to design a new surface for the famous ancient arena. The winning entry, announced in May 2021, is by a team comprising the Italian engineering practice Milan Ingegneria, the architect Fabio Fumagalli, and the architectural practice Labics.

The task is not straightforward. The floor needs to cover and protect the subterranean warren of rooms, service corridors, and lift shafts that were central to the functioning of the amphitheater and allowed gladiators, animals, and scenery to appear on stage through trapdoors.

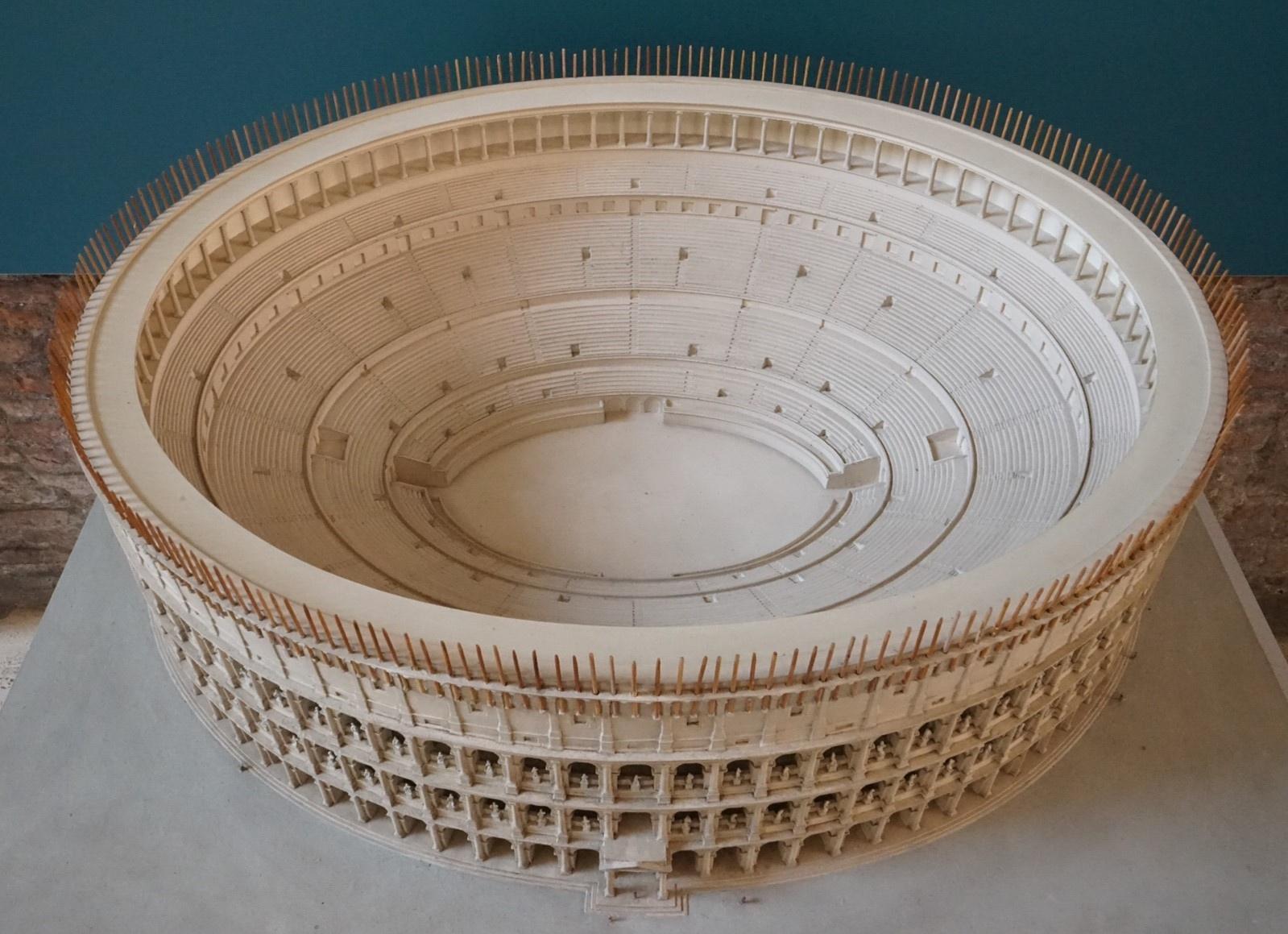

Model reconstruction of the Colosseum.

That the scheme has provoked criticism is no surprise. Any major alteration to the most recognizable monument from the Classical World is going to be controversial. The projected cost of the project is currently 18.5 million euros, and questions, understandably, have been asked about whether spending such a sum on the Colosseum is a priority when many other historic monuments in Rome are in obvious need of investment to carry out fundamental restoration and conservation. Of course, it is possible that the funds have only been made available in the first place because it is the Colosseum, and—as the most visited site in Rome—perhaps it deserves special attention.

Other objections concern what is sometimes labeled the ‘commercialization’ and ‘Disneyfication’ of cultural heritage. This unease arises from the statement by the Parco Archeologico del Colosseo (the body responsible for the monument) that the floor will allow the site to host ‘cultural events of the highest standard.’ The worry appears to be that using the Colosseum for performances—which will presumably generate income—is, in some way, selling out history and affects the dignity of the ruins.

Yet the Roman amphitheaters at Verona in Northern Italy and at Arles and Nimes in Southern France are regularly used for performances; notably, Pink Floyd have twice played in the arena at Pompeii. Across the Mediterranean, plays and concerts are held in ancient theatres, and in Rome itself, the Baths of Caracalla present an annual summer opera series. Such events are both popular and allow a different experience of the structures, giving them further relevance to the modern city and different audiences.

As the Colosseum was originally designed to host spectacles, it does not seem unreasonable that it might fulfill this function again. The idea of preserving historic monuments as unalterable and untouchable ruins is a modern one. There is nothing intrinsic to appreciating and engaging with heritage that prohibits finding new uses for old buildings in a way that is non-destructive (the new floor will be entirely removable without leaving permanent damage).

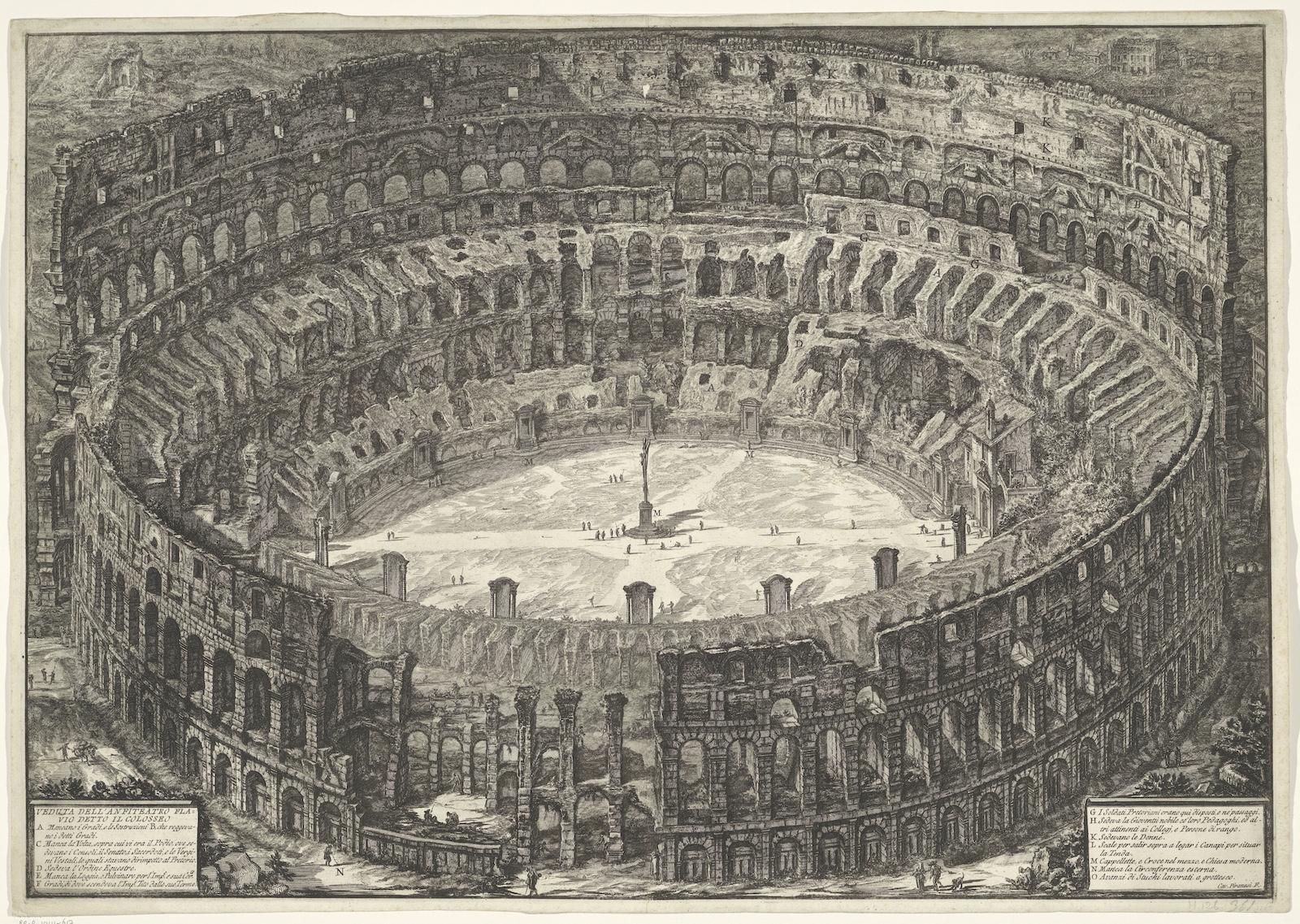

Photograph of the Colosseum by Lorenzo Suscipi from between 1850-1880 showing the earth floor. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The Colosseum, as we see it today, is not ‘how the Romans left it’ and reconstructing the floor does not make it less ‘authentic.’ The brick piers that hold up the outer walls are nineteenth-century additions, much of the south-western side has been rebuilt, the internal staircases that visitors ascend are twentieth-century creations, as is the limited patch of reconstructed seating.

The manner in which we see the Colosseum today is largely a construct of the last two centuries. The ancient wooden floor (itself periodically replaced) disappeared after the amphitheater went out of use in the sixth century AD (although traces were found during the nineteenth-century excavations). Declining into a ruinous state of abandonment, the substructures became filled with an accumulation of silt, waste, and debris, which created the earth floor visible in old drawings and paintings.

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that archaeologists began to clear out this material and expose the ancient underground spaces, with the task only being completed in the 1930s. In the 1990s a section of the wooden floor was reconstructed at one end of the arena, which is how it exists today. The substructures being visible is neither an ancient Roman vision nor a carefully curated presentation of the monument; rather, like many archaeological sites, it is how it has been left after it was excavated.

Photograph of the Colosseum, anonymous, from between 1860-1900, showing partial excavation of the floor. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Reinstalling the floor will create new experiences. Visitors will be able to walk both under the arena and out into its center. This will facilitate a totally different sense of space in the Colosseum, not to recreate ‘what it was like’ but to appreciate the building in a different way.