They are perhaps best known for their peculiar artistic style and iconography—one that depicts amalgamations of humans, plants, and animals in tortuous, exceedingly intricate, and stylized forms that are at once both an intentional puzzle for the viewer and a complex, detailed map of their cosmological and spiritual ideologies.

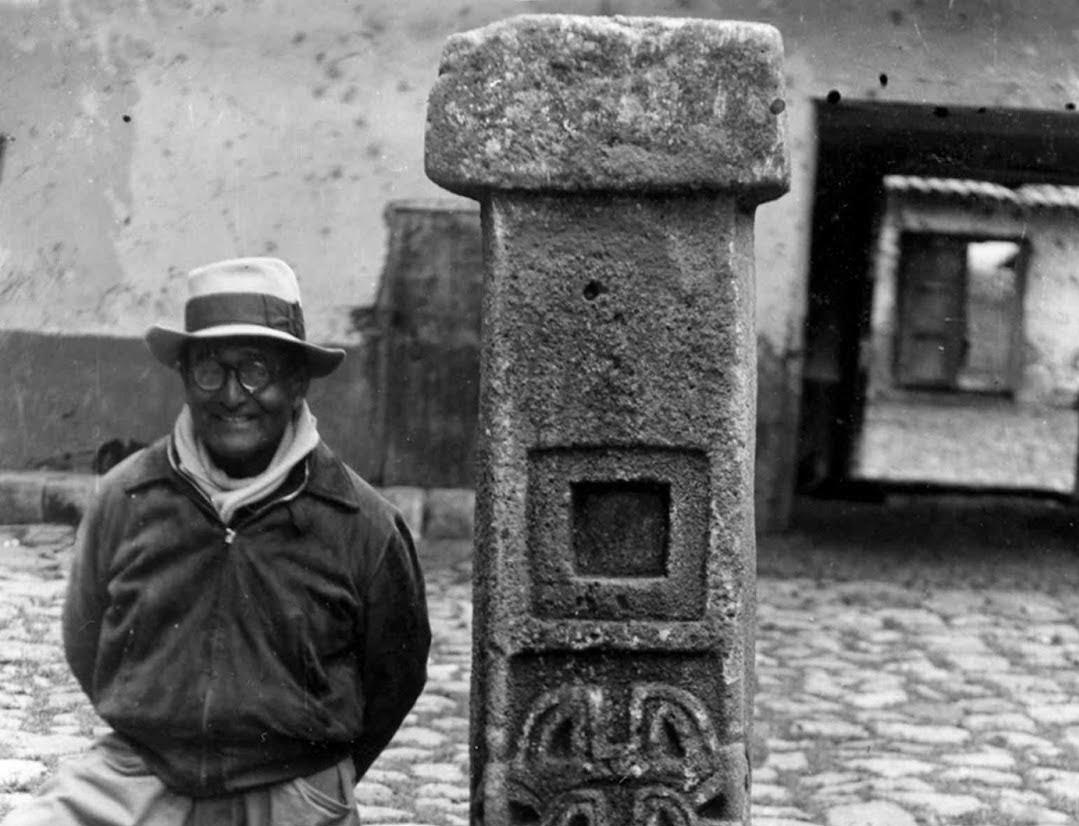

Detail of Peruvian archaeologist Julian C. Tello photographed standing next to the Tello Obelisk, named for his discovery.

The ancient temple complex of Chavín de Huantár sits at the intersection of two turbulent rivers, the Huachecsa and the Mosna, overshadowed by the towering Cordillera Blanca. The site once belonged to a civilization that archeologists call the Chavín, although their true name is unknown.

The Chavín lived in what is now the Ancash region of North-Western Peru during the Middle Formative Period, or the Early Horizon in pre-Columbian South America, a period lasting roughly from 1200-800 BCE. The influence of the Chavín was widespread, and though little is known about their society, evidence of their visual culture can be seen as early as the fifteenth century BCE.

Exterior view of the ancient temple complex of Chavín de Huántar. Photographed in 2014 by Peter Hess.

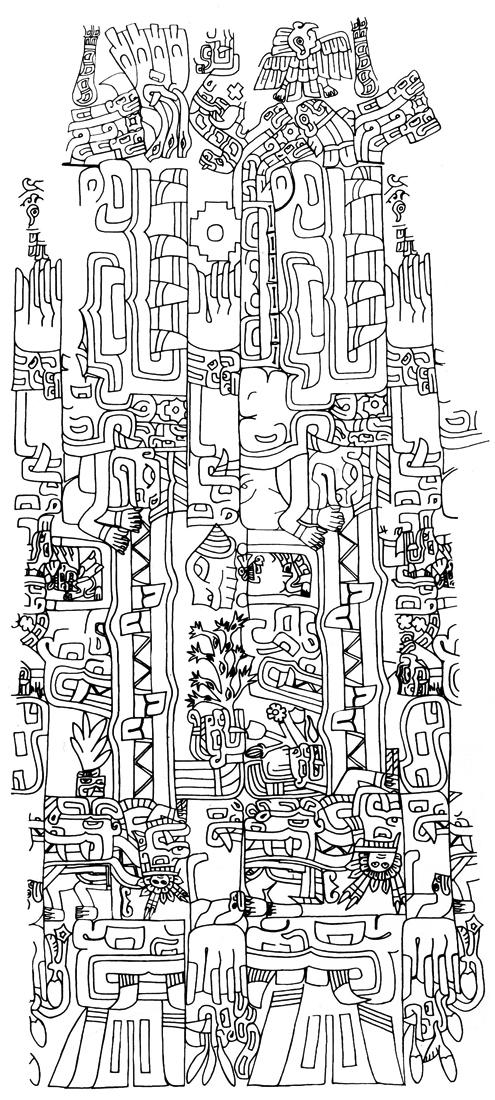

Drawing of both sides of the Tello Obelisk.

They were a powerful presence and one of the earliest complex societies of the Central Andean region. Instances of distinctly Chavín iconography throughout Peru confirm they had a vast and productive trade network, and successfully developed an agriculture-based economy. Certain plant imagery and the discovery of snuff tools also indicates the use of psychoactive drugs.

The site for which they are named, Chavín de Huántar, is most closely associated with the culture and was most likely a political and religious ceremonial center. The flat-top pyramid complex was built in stages, with earliest evidence of construction starting around 1200 BCE. A labyrinth of windowless tunnels and galleries twists through the interior of the main building. It is filled with carvings on large stone slabs, or stelas, that feature designs just as intricate and winding.

Animal and plant depictions are a recurring theme throughout Chavín iconography, both in this temple and beyond. Frequently featured animals include jaguars, caimans, and raptors—representatives of the three earthly realms of earth, water, and sky. They are most often rendered in chimeric forms with semi-human features.

These chimeras are always shown in a semi-composite view—as though flayed and laid out flat. This allows the viewer to see every part of the creature from their most recognizable angle. These complex illustrations often contain hidden elements, such as a jaguar face within the joint of a reptilian leg, or plants and teeth sprouting from orifices. These “images within images” compound until the overall composition is busy with lines, symbols, and figures that are indistinguishable unless broken down and scrutinized.

The phenomenon of the body is immensely important in Chavín iconography and may be representative of the cosmology and spirituality of the culture. Emphasis was placed not only on detailed depictions of the body but also on the processes of the body—the transference and interaction between man and nature. Orifices in particular seem very important as the means by which the body interacts with nature. The ingestion of sustenance and the expulsion of waste symbolize an endless cycle of exchange between an organism and its environment, embodying the unbreakable connection between people and nature.

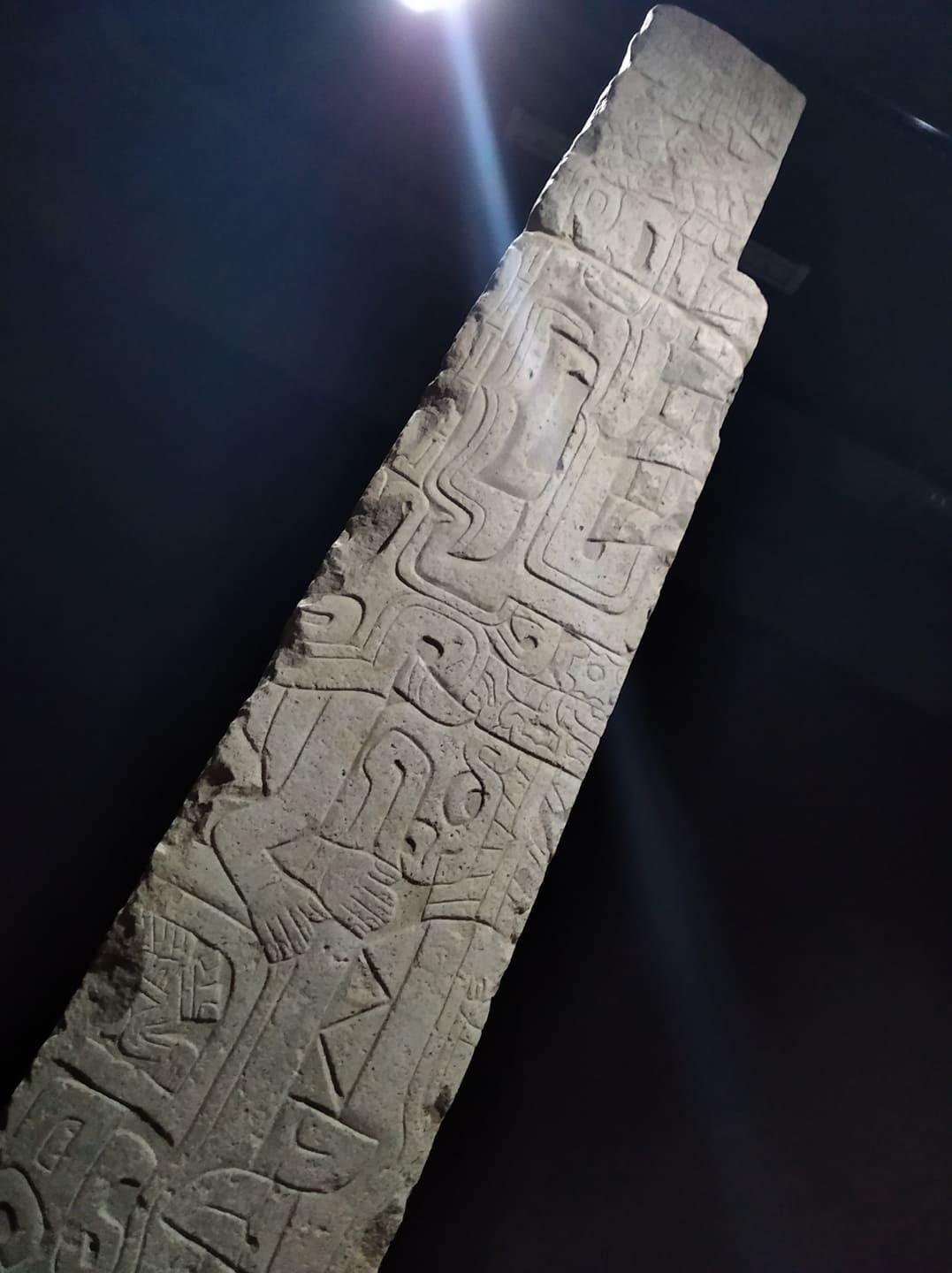

The Tello Obelisk, found at Chavín de Huántar, exemplifies these motifs. Contained within the intricate carving are the fanged jaws of a caiman here, the splayed wings of a bird of prey there—and each element considered separately leads into a dizzying array of embellishments that become another image. It is believed to depict an important deity to the Chavín, and is carved from white granite, a tough igneous rock (notoriously difficult to carve) able to weather the elements and the years with little destruction.

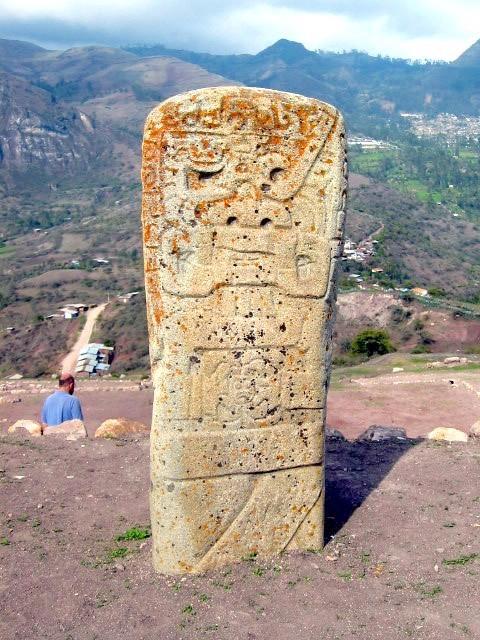

Similar imagery can be found at the religious complex site of Kuntur Wasi in the Jequetepeque Valley of Peru. Occupied from about 1200-50 BCE, the site contains rock sculptures with feline and serpentine motifs in the style of the Chavín. Thus, it is likely that the inhabitants had a close link with the Chavín. The site also seems to have had a similar civic-ceremonial function to Chavín de Huántar.

Though not in its original location, the Yauya Stela, named for the small town in the Ancash region where it was found, bears remarkable similarity to the stelas at Chavín de Huántar. Studies of this stela have been seminal to the understanding of Chavín iconography. It contains reptilian, avian, and feline elements, in addition to a few fish-like motifs. As in other iconography, orifices are emphasized, wreathed with jagged teeth and the faces of animals are hidden within points of articulation such as joints.

Photo of a stela carved in the style of the Chavín at the site of Kuntur Wasi in the Jequetepeque Valley of Peru.

Archeological work continues at Chavín de Huántar, now classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In 2018, burials were discovered at the site by a team of Stanford archeologists; oddly, the graves don’t seem to belong to high-status individuals and may have been from sacrifices.

Though the site has weathered time and natural forces such as earthquakes, floods, and landslides; major environmental change is the largest threat to its preservation. In 1945, the site was partially buried by a flood. Today, flooding from glacial melt caused by climate change increasingly threatens the integrity of the complex.

Chavín de Huántar is far from the only cultural site threatened by climate change. One can only hope its remarkable iconography and monumental architecture continue to withstand the test of time.