Many of the mosaics in the Capitoline collection (Montemartini Centrale is part of the Capitoline Museums) come from excavations carried out between the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. This was a period of dramatic urban transformation in Rome. Following the incorporation of Rome into the newly unified Italian nation in 1870 and the decision to make it the capital, the population swelled within five decades from around 200,000 to over a million people. The accompanying property boom required the clearing and building over of vast areas of the ancient city, which had remained largely uninhabited since the end of antiquity.

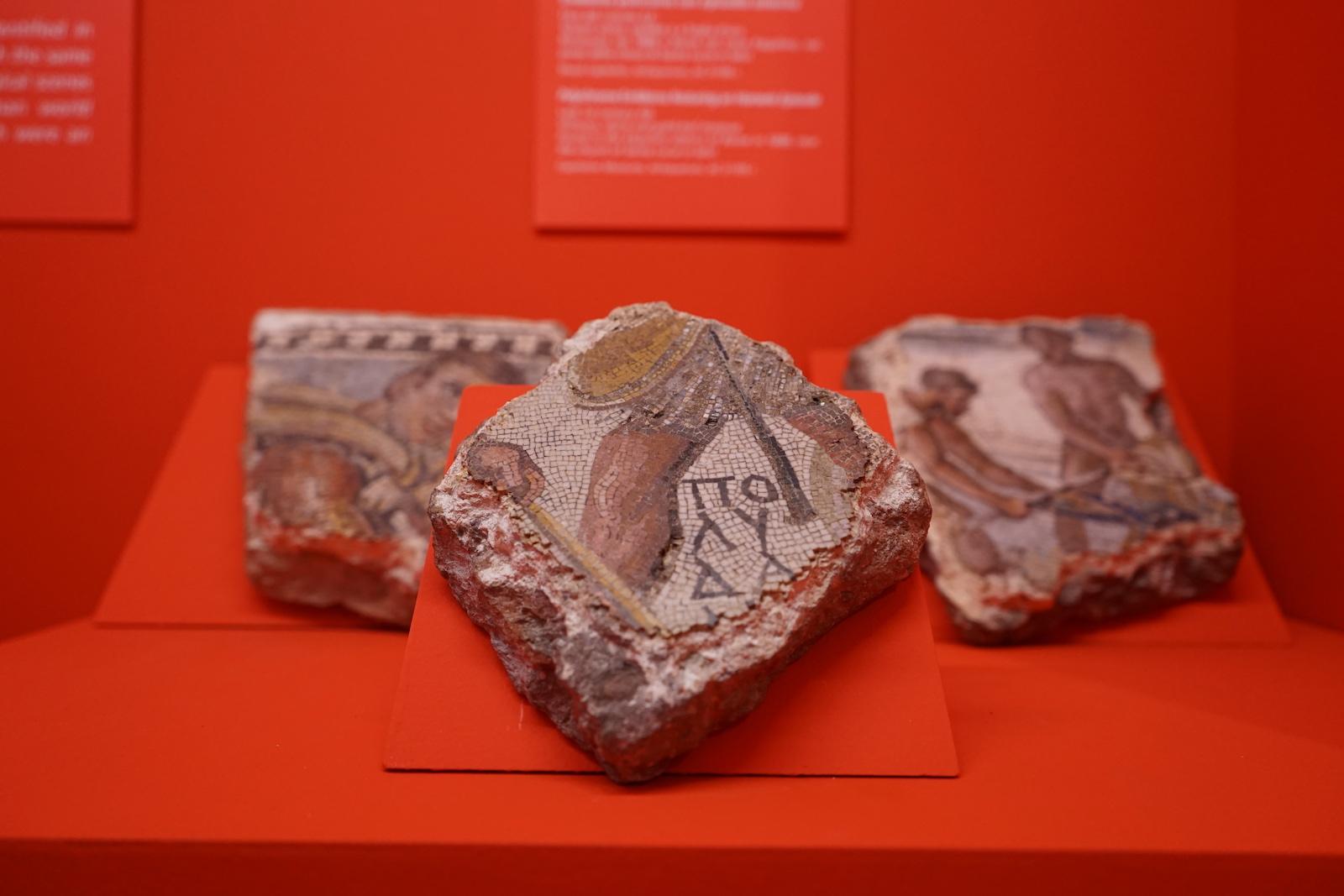

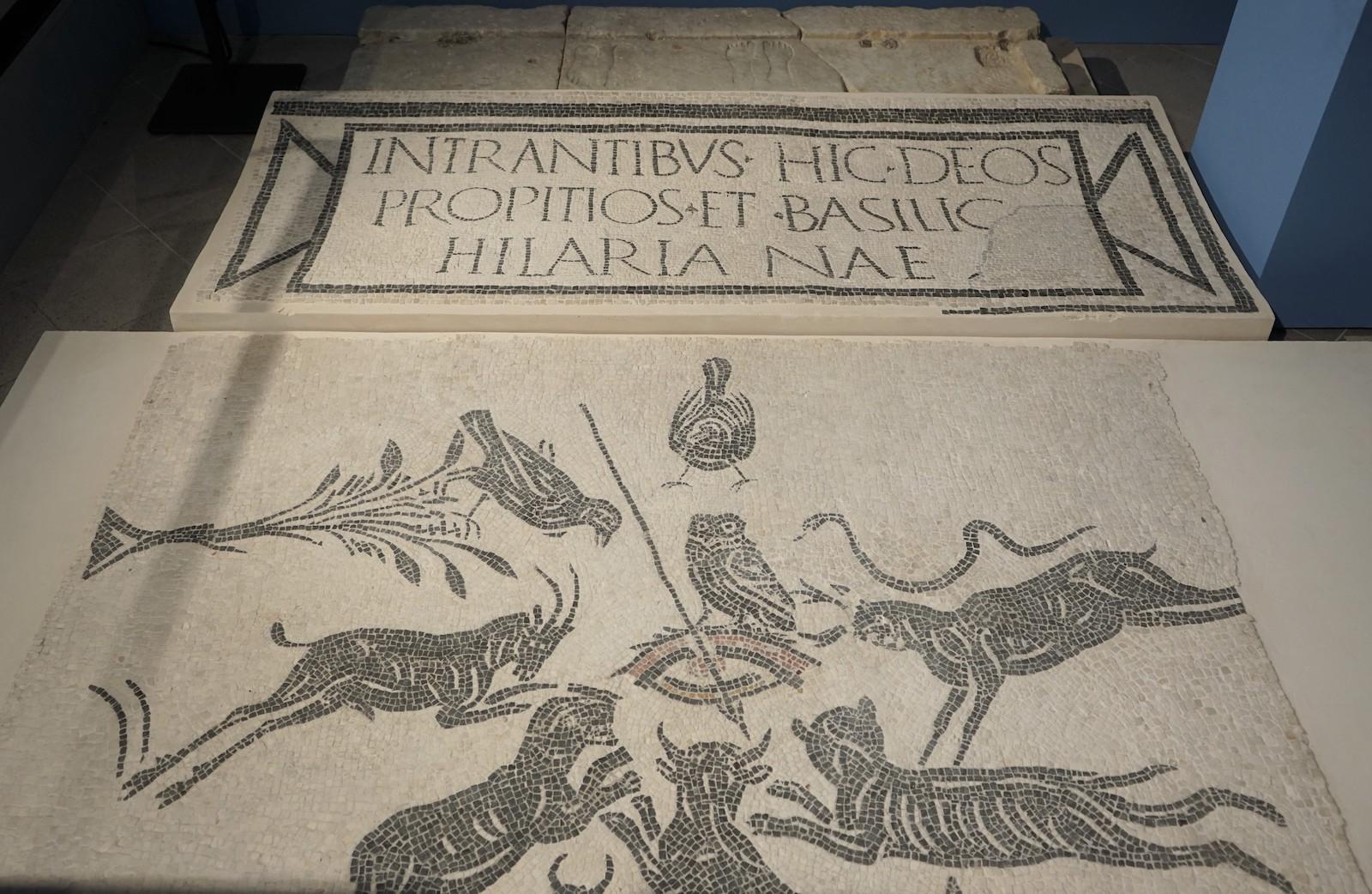

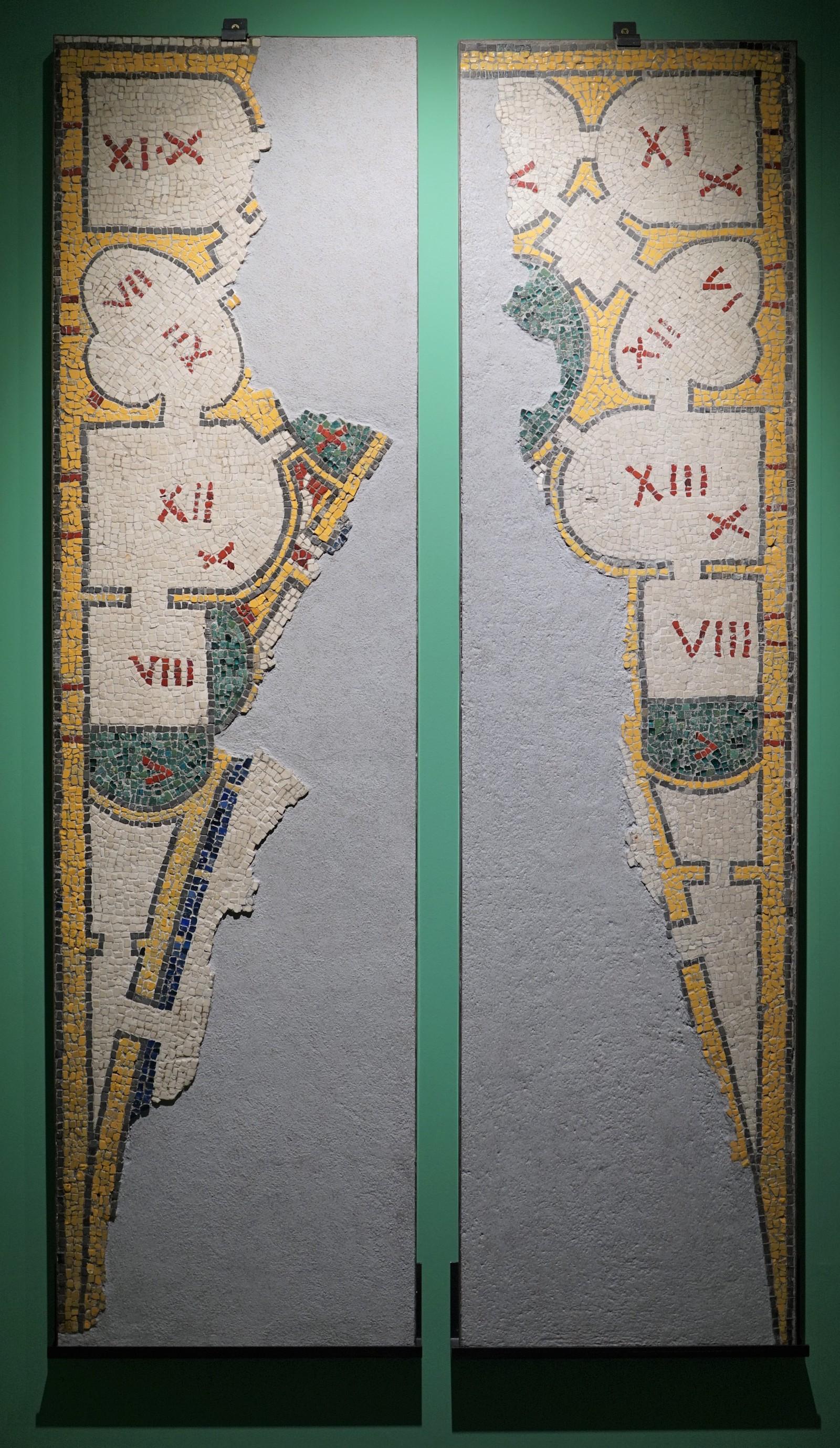

Archaeology was no barrier to development and a huge amount of historical data was destroyed. While many objects were rescued, these were placed in storage, displayed briefly in a museum which opened in 1929 only to close a mere ten years later, and then put back into storage, only emerging on occasion for special exhibits.

The mosaics in this exhibition form part of this remarkable collection and presents the public with an opportunity to see the rich material that is not normally on display and, in some cases, has not been seen in decades.