Indeed, up until recently, Europe’s wealthy patrons commissioned still life paintings of exotic foods to boast of their ability to both buy these foods and afford these works. In an age where all foods are available year-round to many and an excess of it has caused an obesity epidemic in the United States, it is easy to forget that Raphaelle Peale’s 1814 A Dessert portrays expensive and rare oranges, served as dessert at a time when most Americans could not afford the course. Peale, who was based in the northeast, would have struggled to source the fruit for this work, on display in Washington D.C.’s National Gallery of Art.

Raphaelle Peale, A Dessert, 1814.

The November 2021 Focus for Reframed is Feasts and Famine.

Museum-goers, this author included, are often guilty of walking past still life paintings of food, dismissing them as dull and anodyne. Yet, taking in the context of when they were created, these works of feasts and even ordinary fare are often as political as they are historical.

Perhaps the most famous feast in art history is Rembrandt’s circa 1638 painting Belshazzar’s Feast in London’s National Gallery. The Old Testament tale of Belshazzar holding a feast using golden cups looted from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem is memorialized in the work, as God’s writing on the wall tells Belshazzar that his days are numbered. In addition to its religious meaning, the work is a criticism by the Dutch artist of excess and gluttony among the wealthy of his day.

Rembrandt, Belshazzar's Feast, c. 1638.

Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Dog Guarding Dead Game, 1753.

Hunting is a theme that has fallen out of favor in the twenty-first century, when most Americans who are not even vegetarians bristle at being reminded that animals must be killed for us to eat meat; this is particularly evident in supermarkets, where the word 'meat counter' has replaced 'butcher' and signs refer to meat being 'harvested.' Yet throughout most of art history, the depiction of a bountiful hunt was to be celebrated and depictions of dead game acted as a reminder of how precious these feasts were. Dog Guarding Dead Game, Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s 1753 work, depicts specially trained canines who watch over hunted animals so they will not be stolen by vultures.

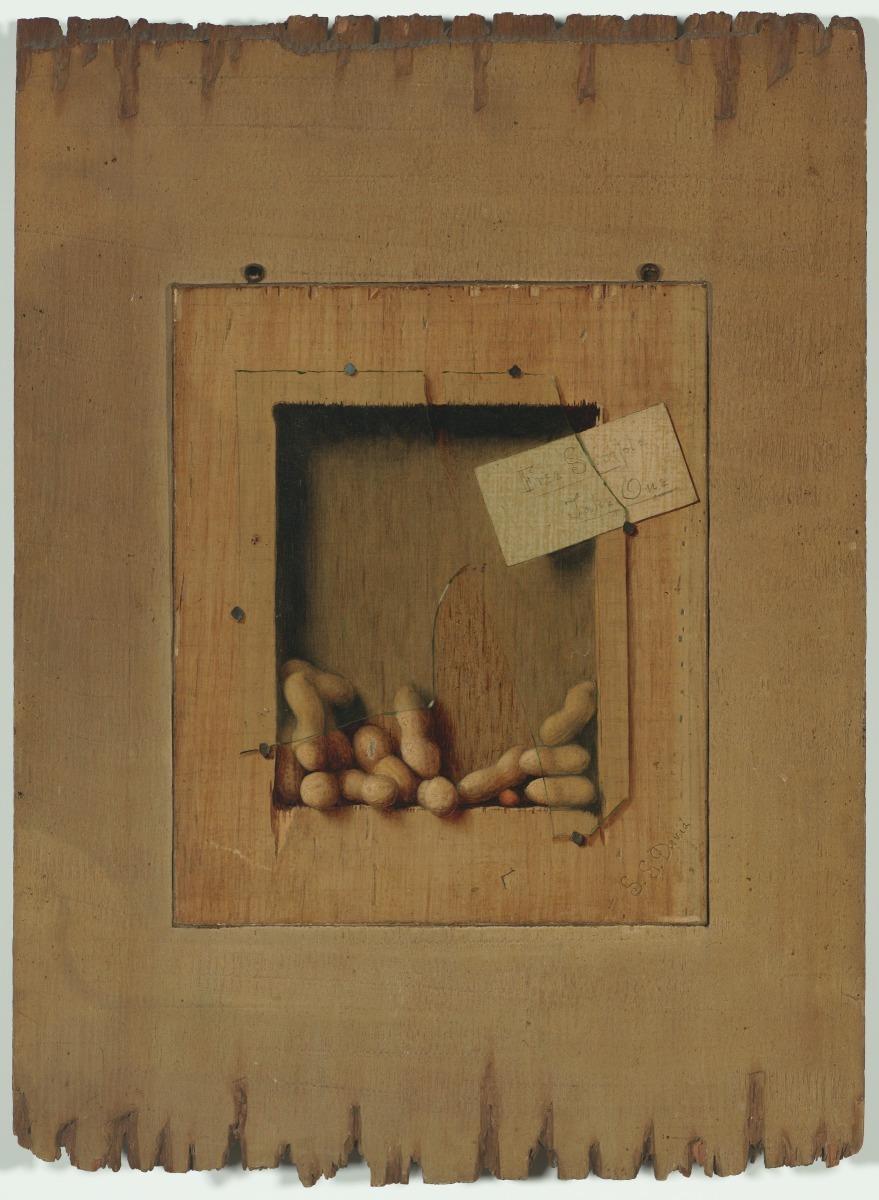

De Scott Evans, Free Sample, Take One, 1890.

The abundance of food can also be political, something nineteenth century American artist De Scott Evans repeatedly confronted in his work. In his circa 1890 trompe-l’oeil 'deception piece,' the artist shows peanuts behind a jagged piece of broken glass. At the time, peanuts were a politically charged food. Grown primarily in the south, peanuts in Evans’ time were largely harvested by freed slaves still living in poverty as sharecroppers. The legume itself was seen as a working man’s food, and the upper classes shunned it, protesting how pedestrians in cities would litter the sidewalks with their shells.

The creation of depictions of food and feasts in art has largely faded today. Yet its most prominent creator, the American artist Will Cotton, depicts sensual women cavorting with cotton candy, ice cream, and macarons. Instead of warning against these excesses as Rembrandt did, however, Cotton revels in them as do the wealthy collectors in the contemporary, billionaire-dollar art world.