At a time when women were vastly underpaid and discriminated against through regulations enforced by the government, Major Armisted used his governmental powers to employ Pickersgill, paying her $404.90 for the larger flag and $168.54 for the smaller flag, no small sum at the time. Pickersgill was a widow earning a meager income as a seamstress, yet the opportunity to craft the Star-Spangled Banner afforded her the opportunity to purchase the very home she was renting and to expand her female-dominated business.

Pickersgill’s Star-Spangled Banner famously inspired Francis Scott Key’s poem that has become America’s National Anthem. Unknown to many Americans, Pickersgill’s flag and Key’s poem rose in tandem to become famous in the United States only after the Civil War was over.

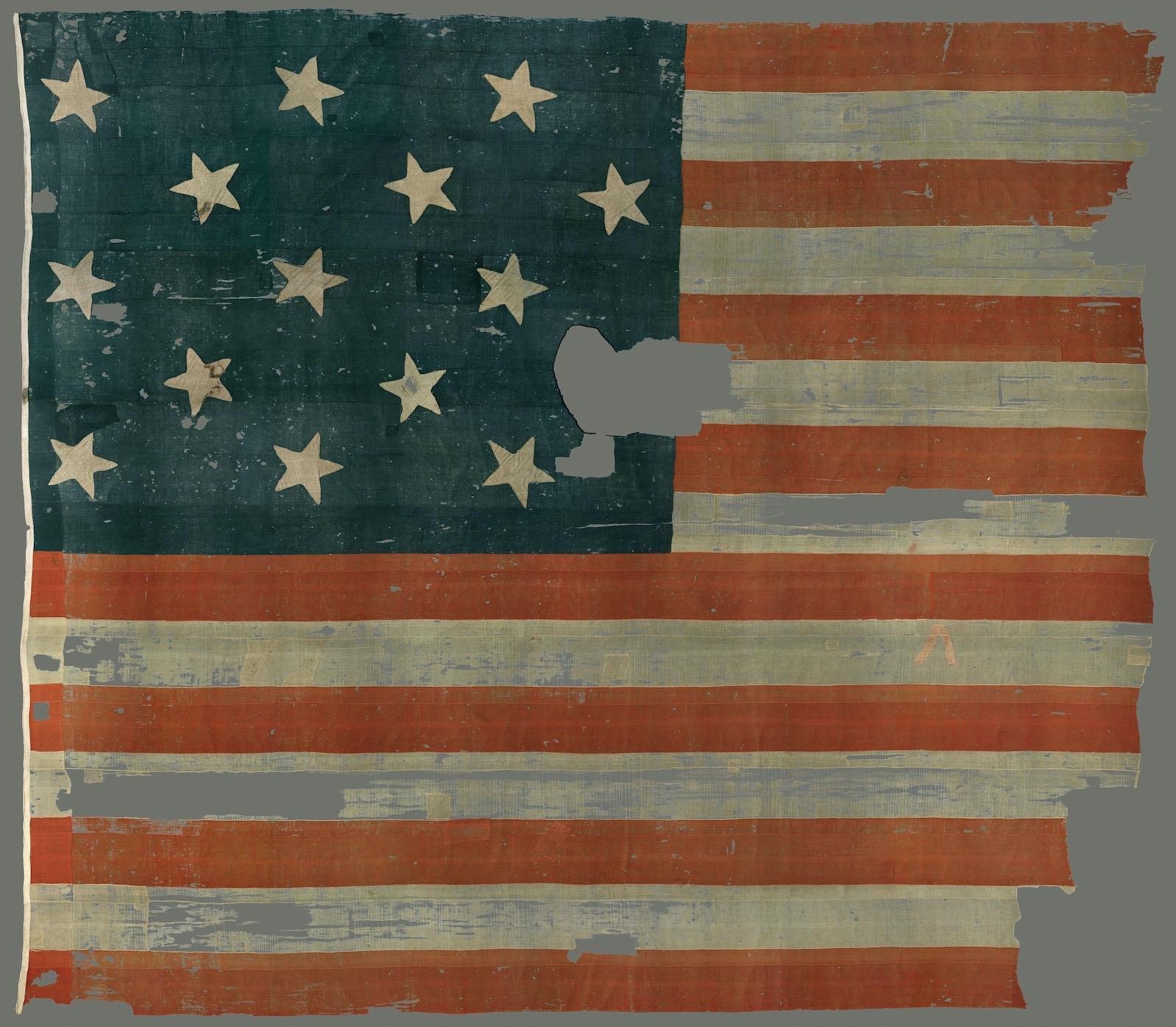

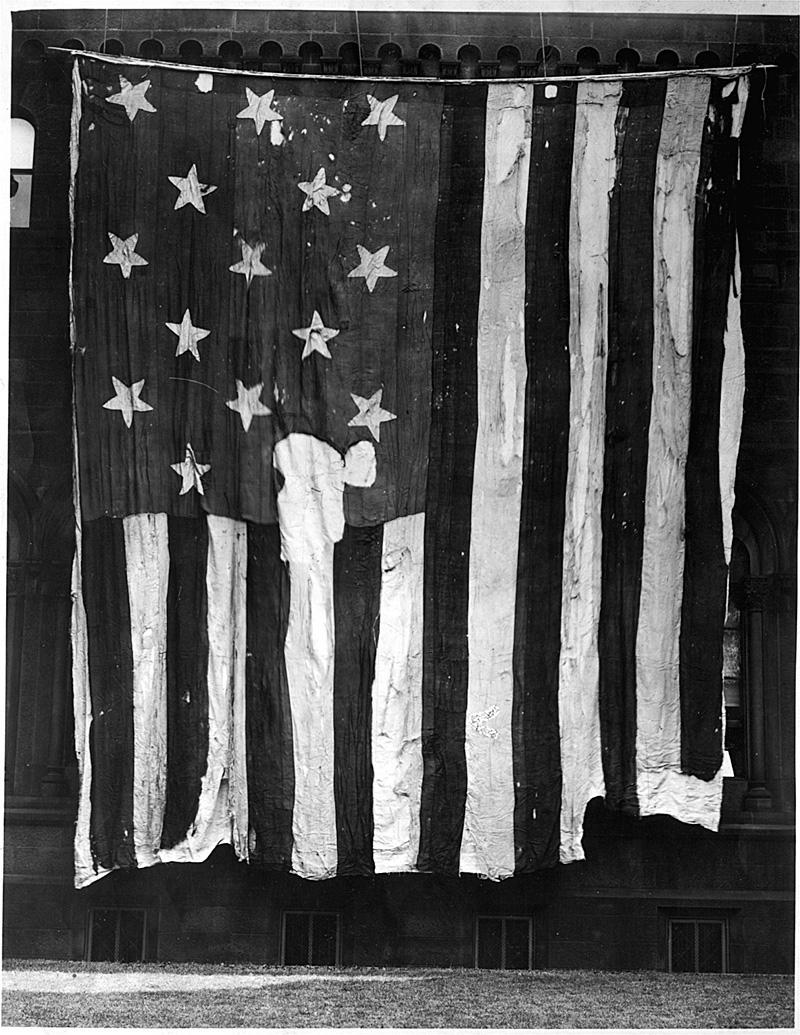

In a bipartisan effort, Hillary Rodham Clinton, (then a first lady), included the flag in the 1998 “Save America’s Treasures” project that Mrs. Clinton spearheaded. Her work saved the flag’s fibers from further decay and was also a bipartisan effort between Republicans and Democrats to preserve U.S. history.

The opinion that the original Star-Spangled Banner is now a work of art is the tried and true view of this Art & Object columnist. Throughout history, no one has agreed on what the definition of “art” is. Yet a common view is that a work of “art” is an “object” that has no practical function, but instead serves as a vehicle through which a viewer can experience emotions, recall memories, and process historical events.

When this columnist looks at this flag, she thinks of the sexism Pickersgill overcame to create the original Star-Spangled Banner. She remembers that Pickersgill did so with the help of a traditionally masculine member of the military, who was not accustomed to working with women but treated her without fear or favor. She thinks of the use of the flag during the Civil War to tear down slavery. She thinks of the use of the flag to reunite a divided country after said Civil War. She thinks of the women marching in the early 1900s for the right to vote. She thinks of all the times that the flag has been waived—in celebrations and in protests—to advance the rights of Americans via patriotism and the waving of the Star-Spangled Banner.