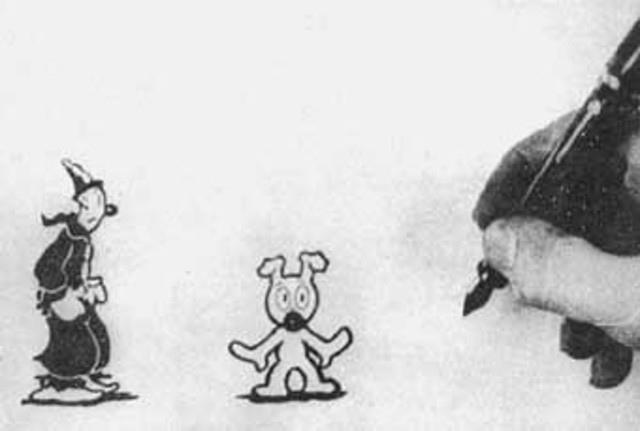

Out of the Inkwell (1918-29), a series starring Koko the Clown, was notable for its early, seamless melding of live-action and animation. Each animated episode began with a live-action shot of creator Max Fleischer drawing or opening an inkwell to 'release' his characters into reality. Sometimes, Fleischer would hand his animations a note or they would leap from the page and run across his desk.

In many ways, the pioneering Willis O’Brien set a decades-long standard for live-action animated movies. The creative worked on the land-mark films The Lost World (1925) and King Kong (1933), creating stop-motion animated sequences while devising and improving many of the systems used to combine them with shots of actors.

For example, The Lost World was the first feature film to use back projection or the rear projection effect. This technique involves filming a full scene of either actors or animated (often stop-motion) characters, projecting that onto a translucent screen from behind, and filming the rest of the scene in front of the projection.