Increasingly, there is a move towards making the archaeology found during construction accessible to the public. For example, the gym of a new hotel shares its space with an ancient porticus; arches of an aqueduct, built by Marcus Agrippa in 19 BC, can be found amid the lines of designer goods in a high-end department store.

Where opportunity (and money) allow, particular sites are even turned into small museums. Beneath the headquarters of a healthcare insurance organization, Museo Ninfeo showcases an ancient, luxury garden complex, belonging at one time to the emperor Caligula.

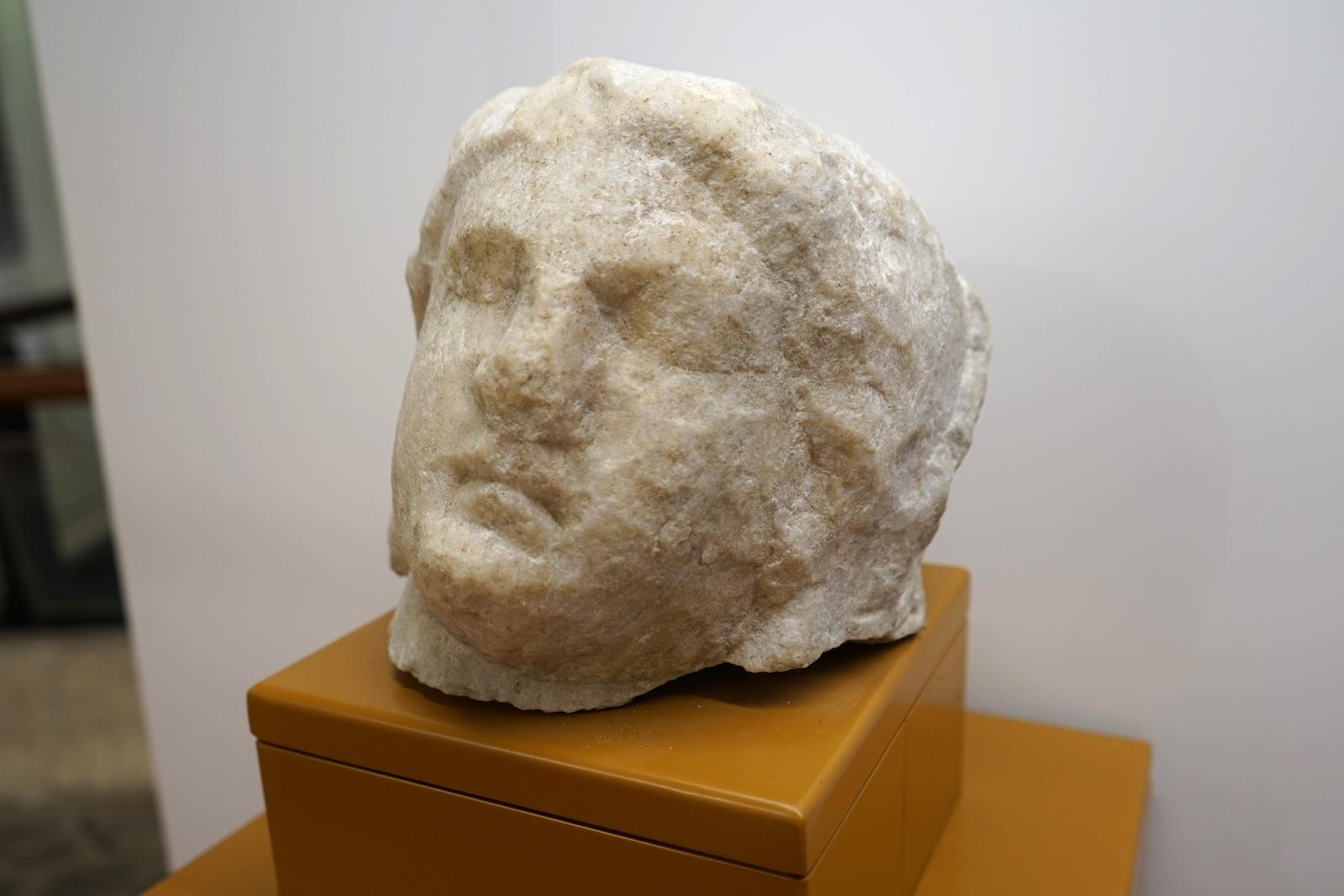

A similar opening, out in the suburbs and much less publicized, was “The Drugstore Museum” in Rome’s Portuense neighborhood, on the far bank of the River Tiber.