His relationship with materials is, to say the least, “unpremeditated.” He engages many media, many genres, and just about anything he can lay claim to—from lumber to glass to performance art to photography. His early work concerned itself with Land and Conceptual projects.

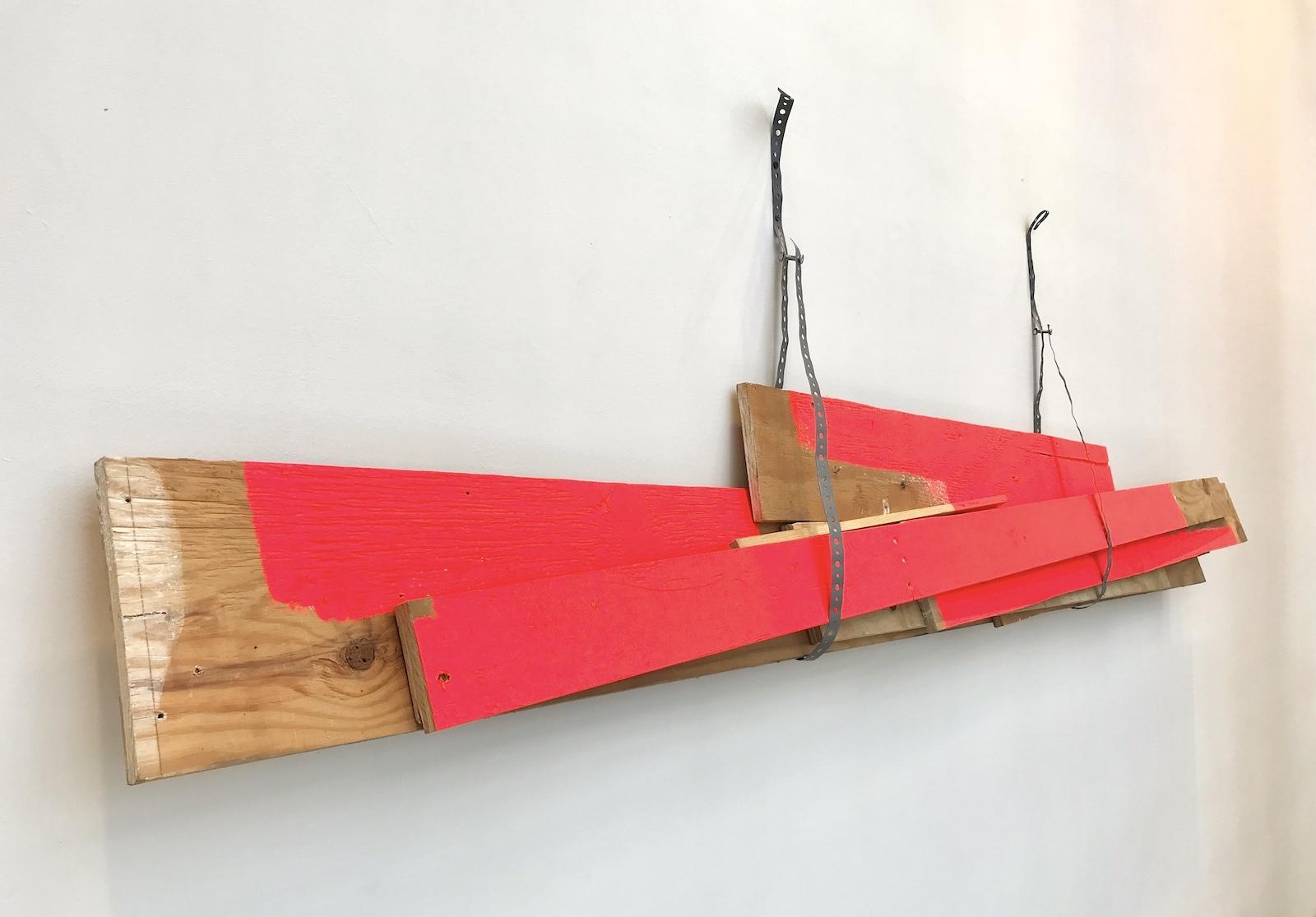

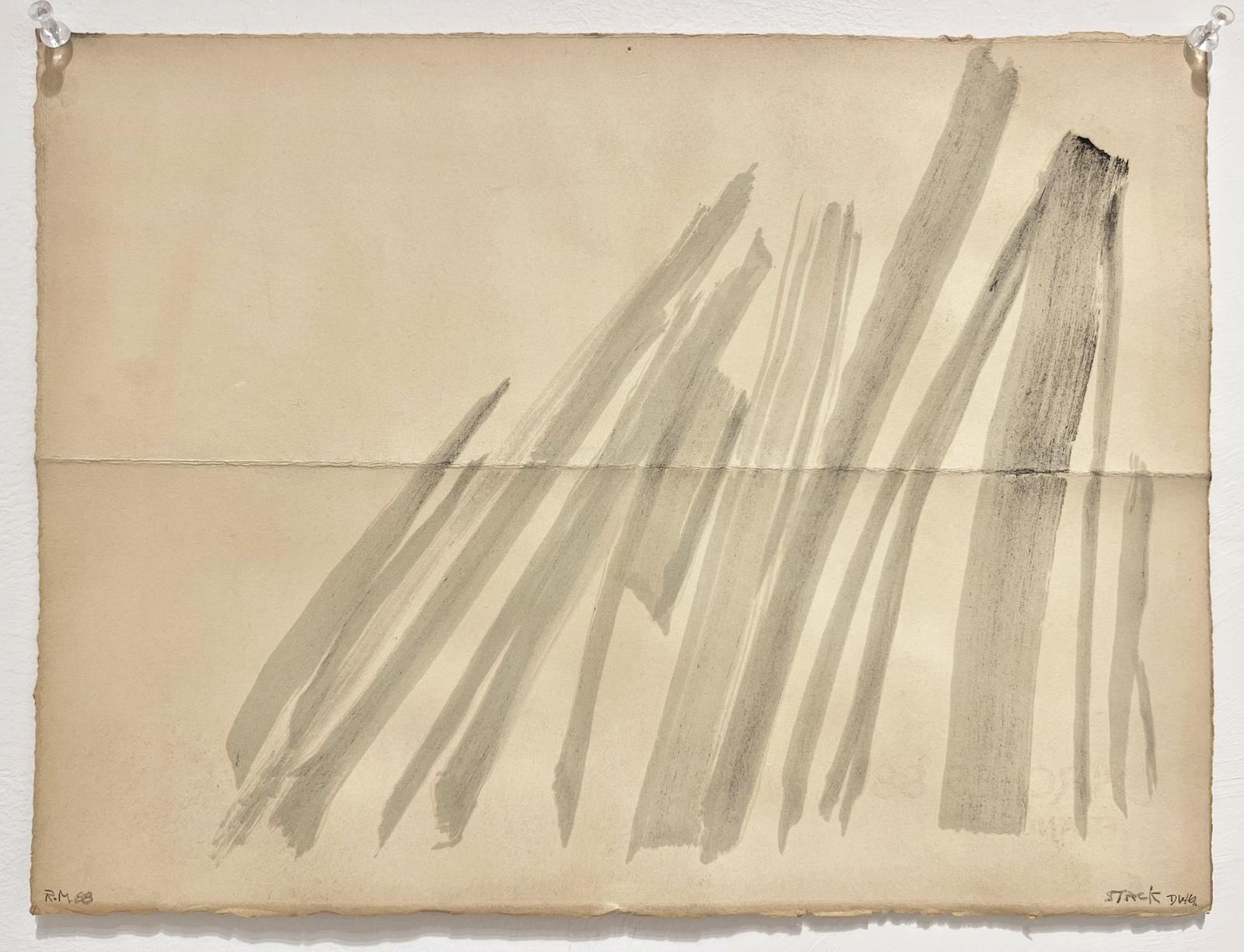

In other words, Maltz accommodates what comes to hand, what the universe offers, wherever he is, and then lets it assemble and shape itself, with components often appearing self-framed in their painted or raw edges. He explores what is there and what is around it. This is clear in his geometric “Ball Park” Series (1977-2012) and an installation from an 2012 international group show in an Oaxaca, Mexico warehouse, where the materials he was to use hadn’t arrived in time for the exhibition so he had to substitute with what the warehouse offered: cinder blocks, which he stacked and painted in Day-Glo colors. Miraculously, it worked, demonstrating Wittgenstein’s precept that the world is made up of facts, not things, taking facts to be what the creator does with the found universe.

In most of his art, light is the primary ingredient, for the simple reason that it’s either there (or not there) and beyond his control. “It’s natural, not premeditated,” Maltz says. “You don’t have to get the lighting just right,” he adds, “The lighting is always different from when I make the work.”

Incidentally, it turns out, Maltz’s father, Scottie Maltz, was teaching a course in lighting design at Ringling College of Art and Design in 2006 when Maltz was making a project and lecturing there. All of which compounds the artist’s affinity for the coincidental and elaborates the associability of his life and work.