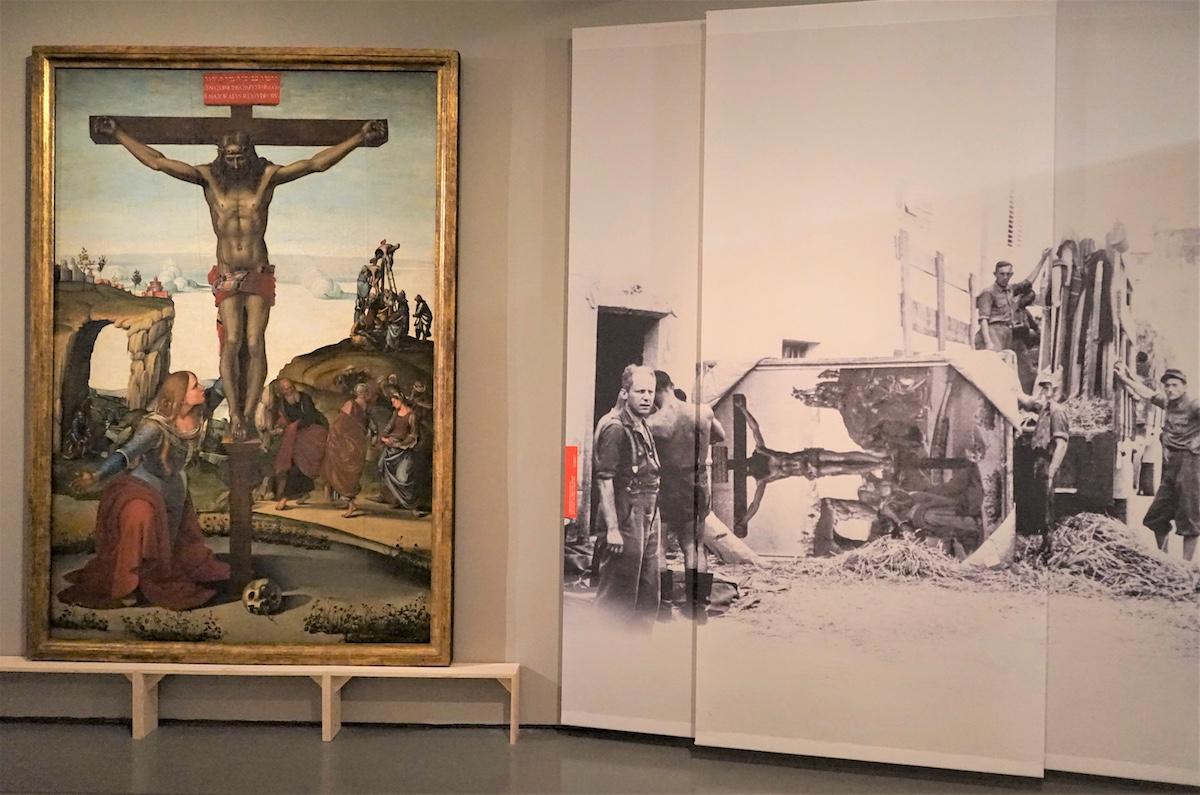

At the Quirinal Palace in Rome, the exhibition ‘Arte Liberata 1937-1947’ focuses on the Italian museum curators and civic officials who acted to save works of art across the country during the war. Giuseppe Bottai, minister of national education at the time, laid out plans a year before war broke out to identify and prepare for storage of the pieces most at risk and of the greatest artistic interest. Likewise, Luigi De Gregori was instrumental in organizing the protection of rare books and manuscripts from collections across Italy. More dramatic are the accounts of Francesco Arcangeli cycling between the shelters where works of art were stored, despite Allied bombing, and Italo Vannutelli’s rescuing paintings from the town of Viterbo while avoiding columns of German soldiers.

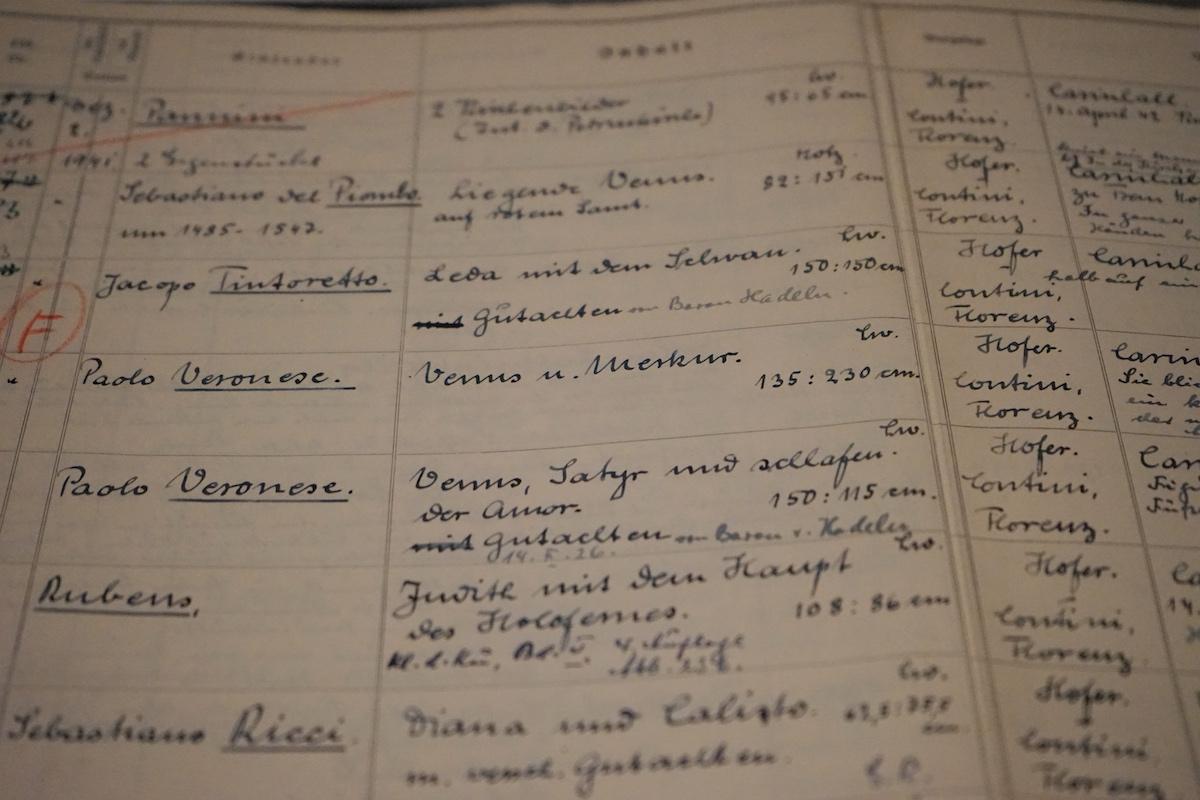

On display in the exhibition are one hundred works of art connected to these stories. The eclectic assemblage includes paintings by Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, and El Greco, Roman-era bronze statues from Herculaneum, musical scores by Rossini, and illustrated manuscripts.

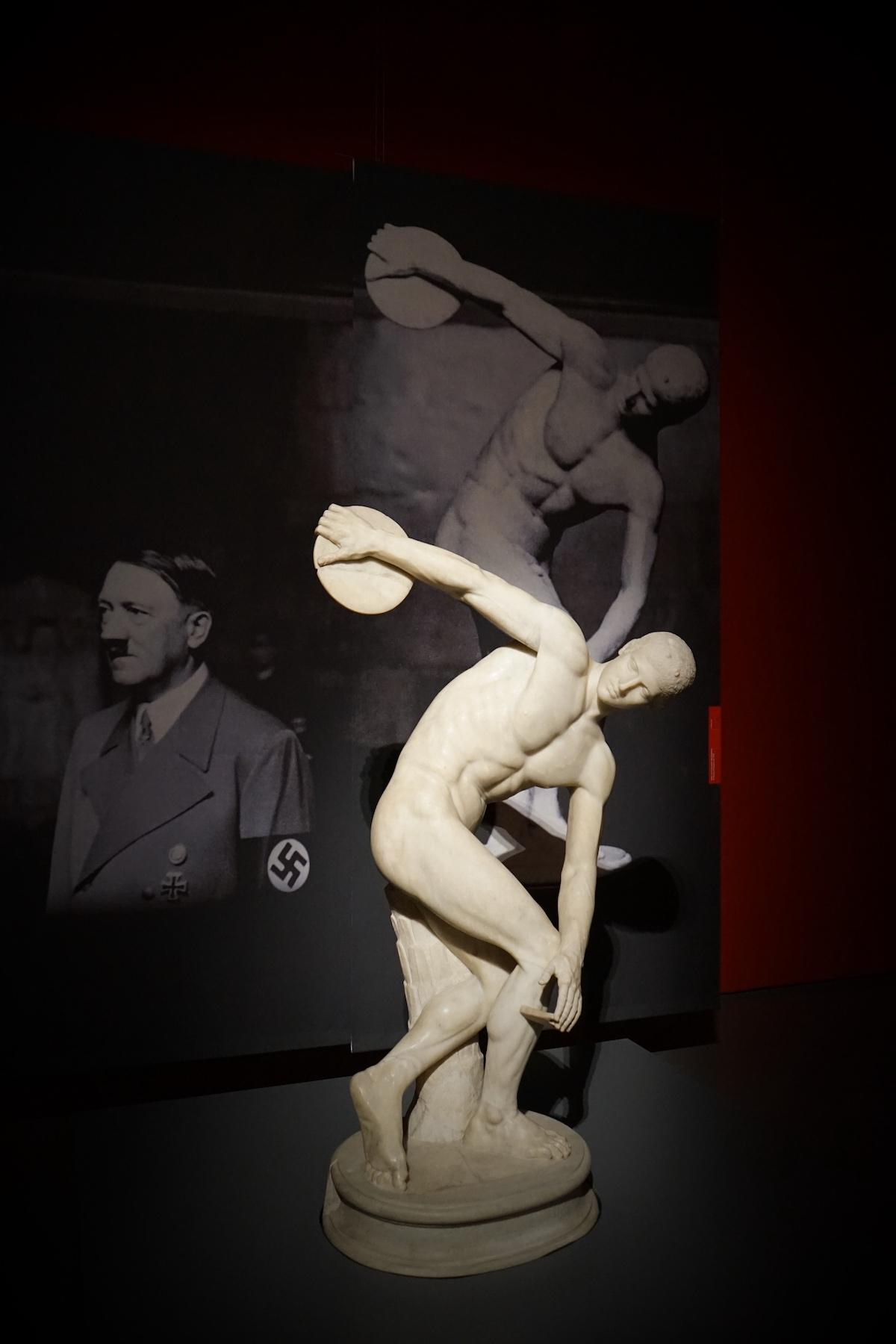

The exhibition opens with an ancient marble statue of a discus thrower (discobolos). Discovered in Rome in the eighteenth century, the piece was exported to Germany before the war in 1938 and displayed at the Munich Glytothek Museum, having been acquired by Hitler and gifted to the German people. Perceived as representing the ideal man, the statue was meant to be placed in the never-realized ‘Führer Museum,’ in Hitler’s hometown of Linz in Austria.