The exhibition is expansive, including approximately 160 objects dating from the early nineteenth century through the present. While painting is at its core, drawings, sketchbooks and journals, prints, photographs, furniture, clothing and textiles, video, and other objects (scientific instruments and mediumistic/occult paraphernalia, including Ouija boards and planchettes) provide a context for doubters to understand ideas that, at first glance, are incomprehensible. Cozzolino explains, “The exhibition delves into how these works relate to both personal and collective narratives of the haunted, the spiritual, and the cosmic.”

John Jota Leaños, American (Xicano-Mestizo), still from Destinies Manifest, 2017. Digital animation, installation, 7 minutes. Commissioned by the Denver Art Museum.

America is haunted. That is the premise of Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art, the first major museum exhibition to take a comprehensive look at the relationship between American artists and the unseen forces that lurk in our cultural history.

Organized by Robert Cozzolino, the Patrick and Aimee Butler Curator of Paintings at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), the exhibition digs into the part of the American identity that, as Cozzolino so aptly states, “is about the imaginative capacity of humanity to consider what lies beyond tangible existence, and how this is reflected in visual culture.”

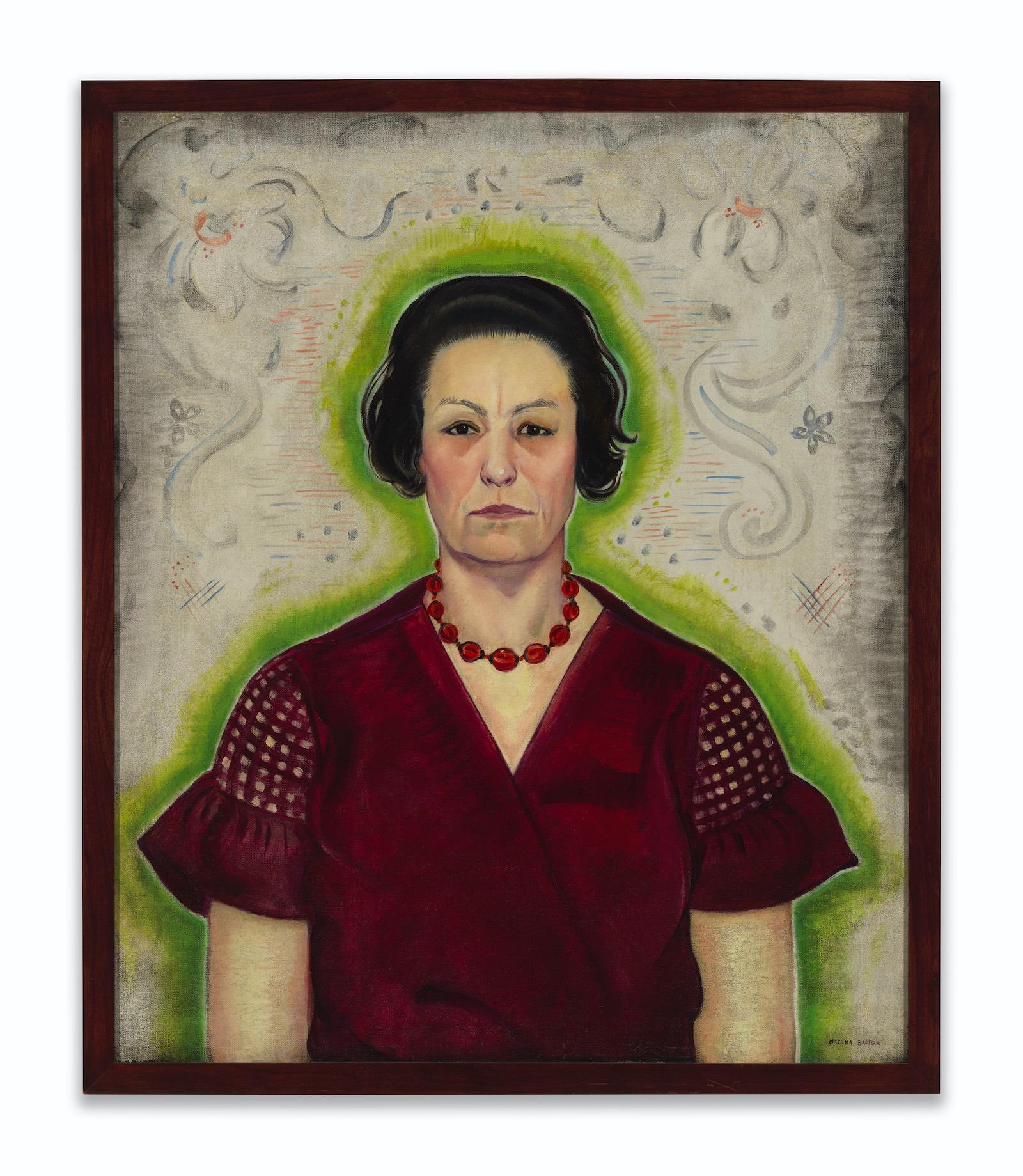

Macena Barton, (American, 1901–1986), Untitled (Portrait of Mother), 1933. Oil on canvas. 311/4 × 261/2 in.

Rather than further exoticizing this unexamined aspect of American art history, this curator’s approach to the artist’s lived experience features empathy and seems guided by a desire to provide context to work that has been marginalized, often regarded as weird, or categorized as “Outsider Art.” The show is organized around four primary themes. The first, America as a Haunted Place, deals with the lingering effects on the environment of the ghosts from our past. Next, Apparitions demonstrates how artists visualized spirits from literature and first-hand experience and then Channeling Spirits/Ritual engages people from the spiritualist community. Lastly, Plural Universes presents artists who bridge the overlapping worlds of science, technology, and speculation including UFOs and extraterrestrial sightings.

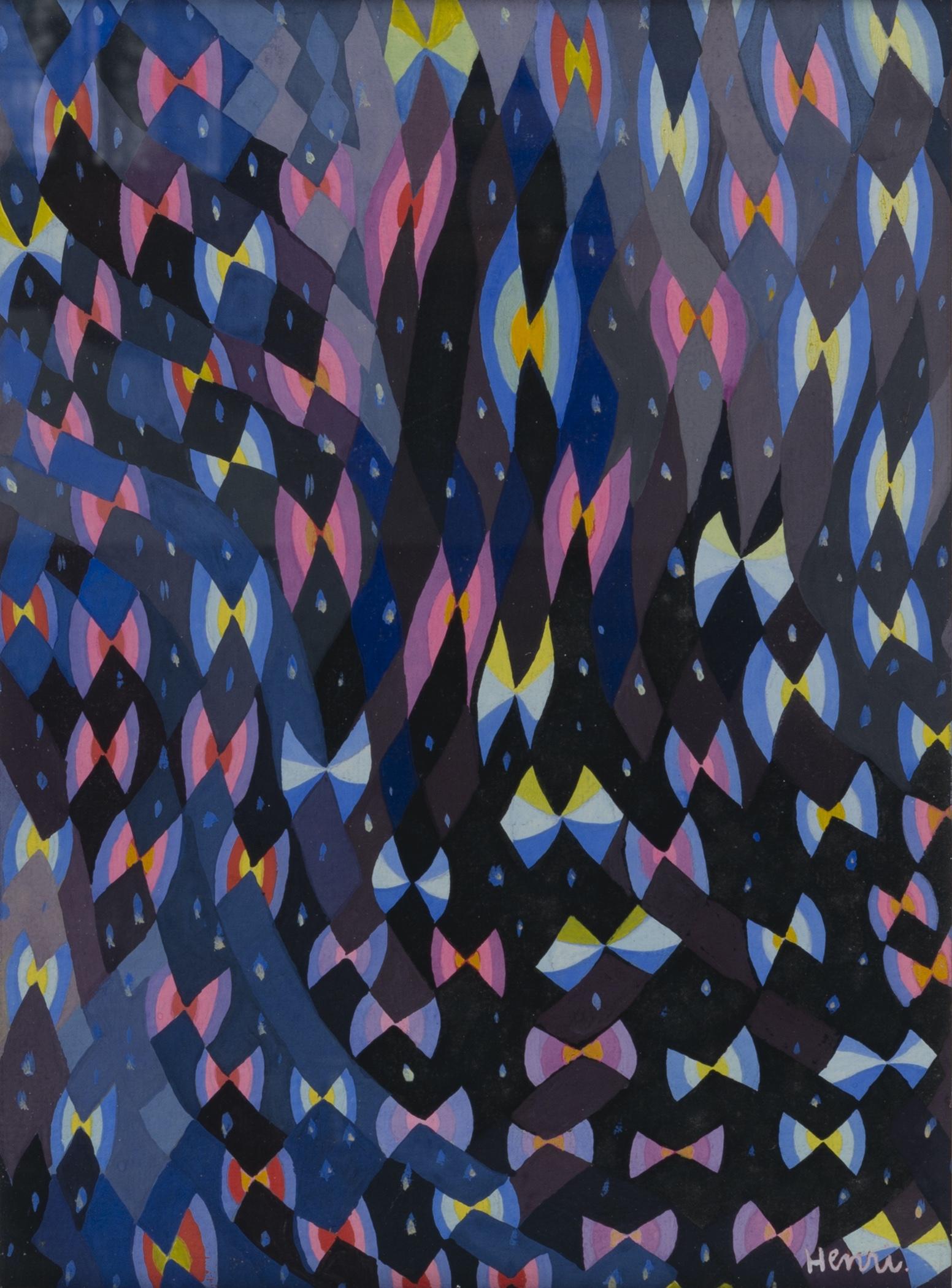

Henriette Reiss (American, born England, 1889–1992)

Frederic Chopin Impromptu A Flat Major, ‘Carefree,’ before 1939. Tempera on paper, mounted on backing, 11 3/4 × 8 5/8 in.

Recognizable names like the Magic Realist painter Ivan Albright (1897-1983) from the past and multi-media installation artist Tony Oursler (1957-) from the present mingle with artworld unknowns. Albright’s obsessive rendering of decomposing flesh in his self-portraits, some of which took years to complete, hover somewhere on the journey between life and death and earned him the title of “master of the macabre.” Oursler took a very active role in the exhibition along with fellow artists Renee Stout (1958-) channeling her alter ego Fatima Mayfield, and the Mestizo (Xicano/Italian/Chumash) new media artist/activist/filmmaker John Jota Leaños (1969-). They participated in a free-wheeling discussion for the press hosted by Cozzolino, prior to the exhibition opening.

The legendary artist Betye Saar (1926-) whose work in assemblage pays homage to the African American experience, was inspirational for Stout. During the press briefing, Stout explained, “I started to understand the different roots of African alternative spirituality. As I gradually grew into this character…the door to my ancestors was opened.” Stout went through a process of self-actualization. She felt the spirits were always around her and we feel them too in her installation, The Rootworkers Table.

Renée Stout (American, born 1958), The Rootworker’s Worktable, 2011. Altered and reconstructed table, blown and hot-formed glass, found and constructed objects, oil stick on panel, found carpet. 78 x 50 x 30 in.

John Jota Leaños explores the imagery and the myths surrounding white settler colonialism in his work. He states, “Americans are great at denial... but they are haunted by their genocidal past.” Contemporary Indigenous iconography invades the pastoral landscapes in Leaños’ Destinies Manifest. This work harkens back to the famous 1872 John Gast painting American Progress that visualizes Manifest Destiny. An essay by Leaños further elucidates his perspective and is included in the extensive catalog.

“Cosmic interconnections through the medium of technology,” are integral to Dust, a difficult to describe unless you’ve seen it piece by Tony Oursler. The artist elaborates, “Dust came about through using amorphous materials and reminds us of what we are all made of.” Oursler explains that his work enthusiastically supports “the way technology extends the psyche,” and he uses techno-devises that eerily seem to connect the viewer to other realms.

It seems that, for many artists, the paranormal is normal. This exhibition provides an introduction to this world via artworks that were new to this writer. For example, the strange dreamlike paintings by Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-1977) are illuminated by an otherworldly, moonglow light. Perhaps being raised in a religious household as a Christian Scientist played a role in her development as did her discovery of the surrealist Magritte.

Columbia Industries, Mystic Answer Board, ca. 1940s. Wood, pigments. 12 x 18 in.

Modern art criticism has been predominantly secular. Cozzolino, having actively engaged the spiritualist community in the planning of the exhibition, emphasized the collaborative aspects of much of the art seen here. Some of the artists worked directly with spirit mediums. All the artists have had some form of supernatural experience and Cozzolino addressed those experiences with seriousness and a desire to reach a greater level of understanding. He expressed hope that the exhibition will shed light on the fact that “the spectral imagination and so-called anomalous experiences have been central to American art and the lives of innumerable artists.”

The Mia’s director and president Katherine C. Luber has promised to host a séance in the museum during the course of the exhibition.