Tina Freeman, a photographer based in New Orleans and a curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art, has been documenting Louisiana’s wetlands for almost a decade. Rather than focusing solely on the effects of climate change—the rising sea levels in Louisiana, for example—Freeman looks at causes as well. Starting in 2011, Freeman took a series of trips to Antarctica to photograph the continent’s glaciers. A few years later, she made her first visit to Avoca Island, a small island in the Louisiana wetlands. During that trip, she noticed that the photographs she had taken in Antarctica eerily mirrored what she was seeing in Louisiana, at least on a formal level. “I noticed similarities between what I was seeing on Avoca and one of the icebergs I photographed in Antarctica,” Freeman says. “There was this horizontality that just made it click, and I realized what was going on.”

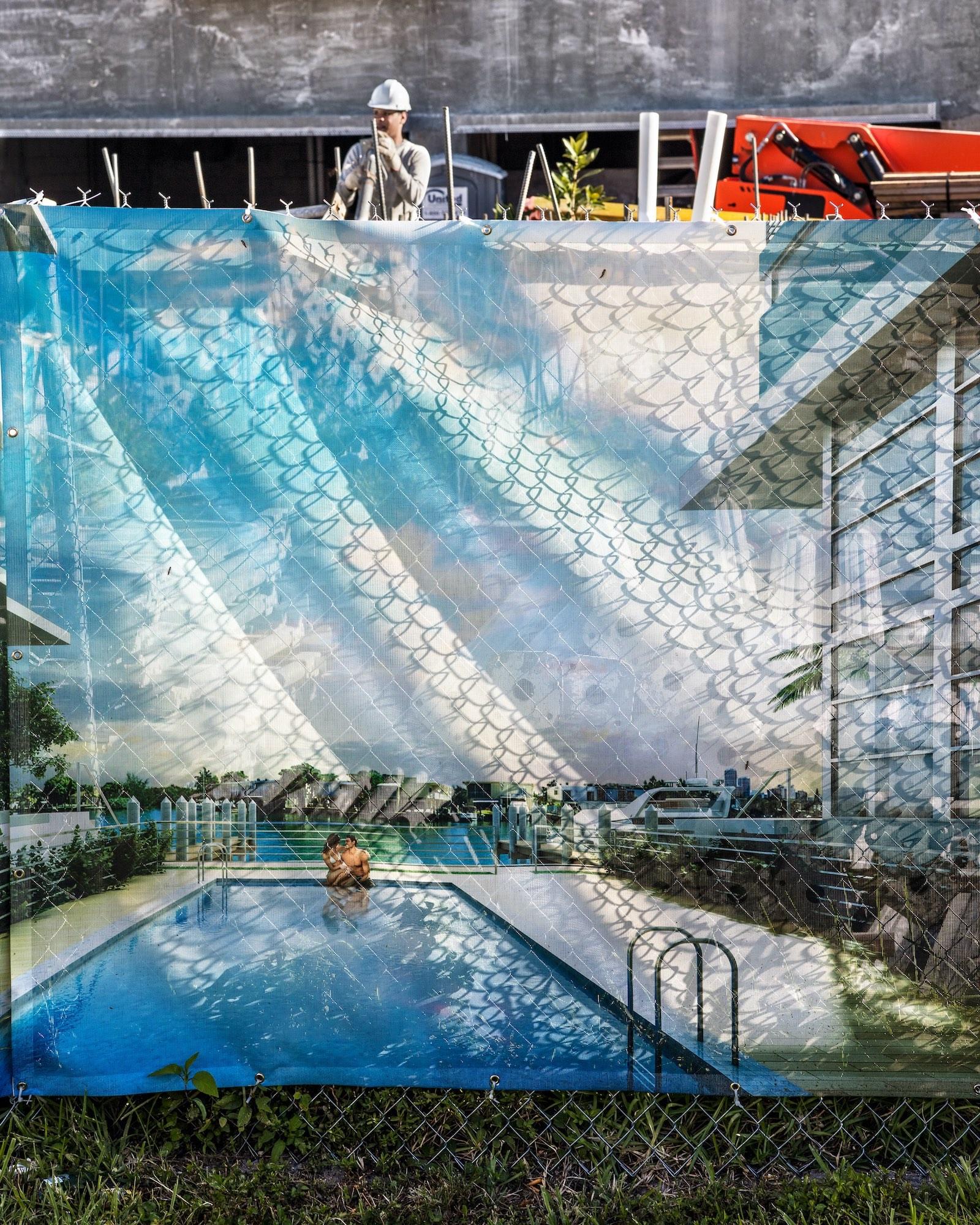

Anastasia Samoylova, Construction in South Beach I, 2018.

On a map of the United States, Louisiana appears to splinter off into the ocean, breaking apart into thousands of tiny, marshy pieces. And with every year, those pieces of wetland grow smaller and farther apart. Since the 1930s, more than 2,000 square miles of land have disappeared into the sea. That land serves an important purpose: it’s a buffer against storm surges and rising sea levels. Without it, most of Southern Louisiana is at risk of catastrophic flooding.

The most severe impacts of climate change on the Gulf South—the coastal states surrounding the Gulf of Mexico—have been thoroughly documented by photojournalists. After every hurricane, a slew of photographers capture the devastation and sorrow wrought by the recent storm. For an artist documenting the region’s changing environment, the question becomes: how do you push past the noise and produce something greater than an archive of someplace soon to disappear? Southern photographers often find themselves moving beyond photojournalism, using the photographic language to contextualize the scale and impact of a changing climate.

Left: Tina Freeman, The Ilulissat Cemetery, Greenland.

Right: Tina Freeman, Cemetery at Leeville, Louisiana.

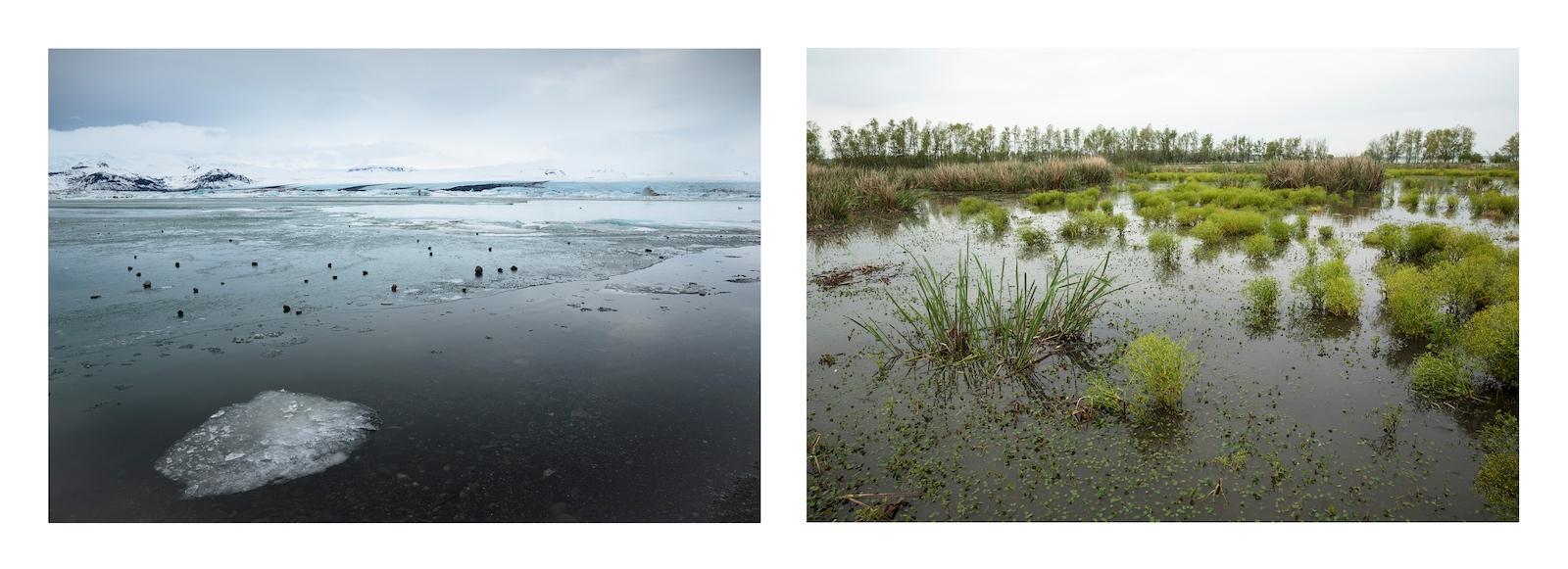

Freeman began to pair photographs of the wetlands in Louisiana with similar compositions taken in Antarctica. The result is deceptively simple and visceral, a reminder of the give and take of climate change. Melting glaciers and coastal erosion are not separate effects of a warming planet, but deeply interconnected events. As the Antarctic ice melts, it raises sea levels and floods out wetlands. In one particularly striking parallel, the shape of a small pond in the Atchafalaya Basin near Lafayette, Louisiana is paralleled with a similarly shaped piece of ice floating off the coast of Svalbard. It’s disorienting — as if the wetland was a parallel world wherein global warming had melted the ice and allowed foliage to spring up in the tundra.

A similar spread in Anastasia Samoylova’s Flood Zones draws a parallel between the outer edges of the wetlands on Key Biscayne, an island off the coast of Miami, and an encroaching housing development. But whereas Freeman examines the global impacts of climate change, Samoylova uses the photographic language to explore the multi-layered nature of the changing environment in Miami. She captures the curious visuals of climate change in the city and the oftentimes bizarre responses to these changes.

Anastasia Samoylova, Waterfront Houses, 2018.

The photographs in Flood Zones document a city on the precipice of collapse yet devoted to relentless expansion. For years, Miami’s real estate market has been a source of confusion among environmentalists: the city is in imminent danger from rising sea levels, yet the real estate market continues to grow at a dizzying pace. In Samoylova’s vision of Miami, the natural world is constantly threatening to burst into the ever-expanding city. Renderings of new developments are a common motif in the Flood Zone photographs, their utopian vision for a planned community contrasted with the entropic reality of life in the subtropics.

In one photograph, a near-perfect rendering of an apartment building is disrupted by weeds crawling up from the dirty concrete. In another, a rendering of the recently renovated Adams Hotel is bisected by a shadow belonging to a moldy telephone pole. Taken together, the photographs paint a portrait of a city whose very existence is absurd.

That absurdity is intentional, a product of Samoylova’s aversion to vague depictions of climate change. The environment is a broad topic and its visual language is well-worn. “With climate change, I wanted to move away from its abstractness as much as I could,” Samoylova says. “It's too easy to sort of resort to cliche.” She steered clear of visual platitudes about rising sea levels, choosing instead to focus on the sublime landscapes formed by a city on the edge of its own demise.