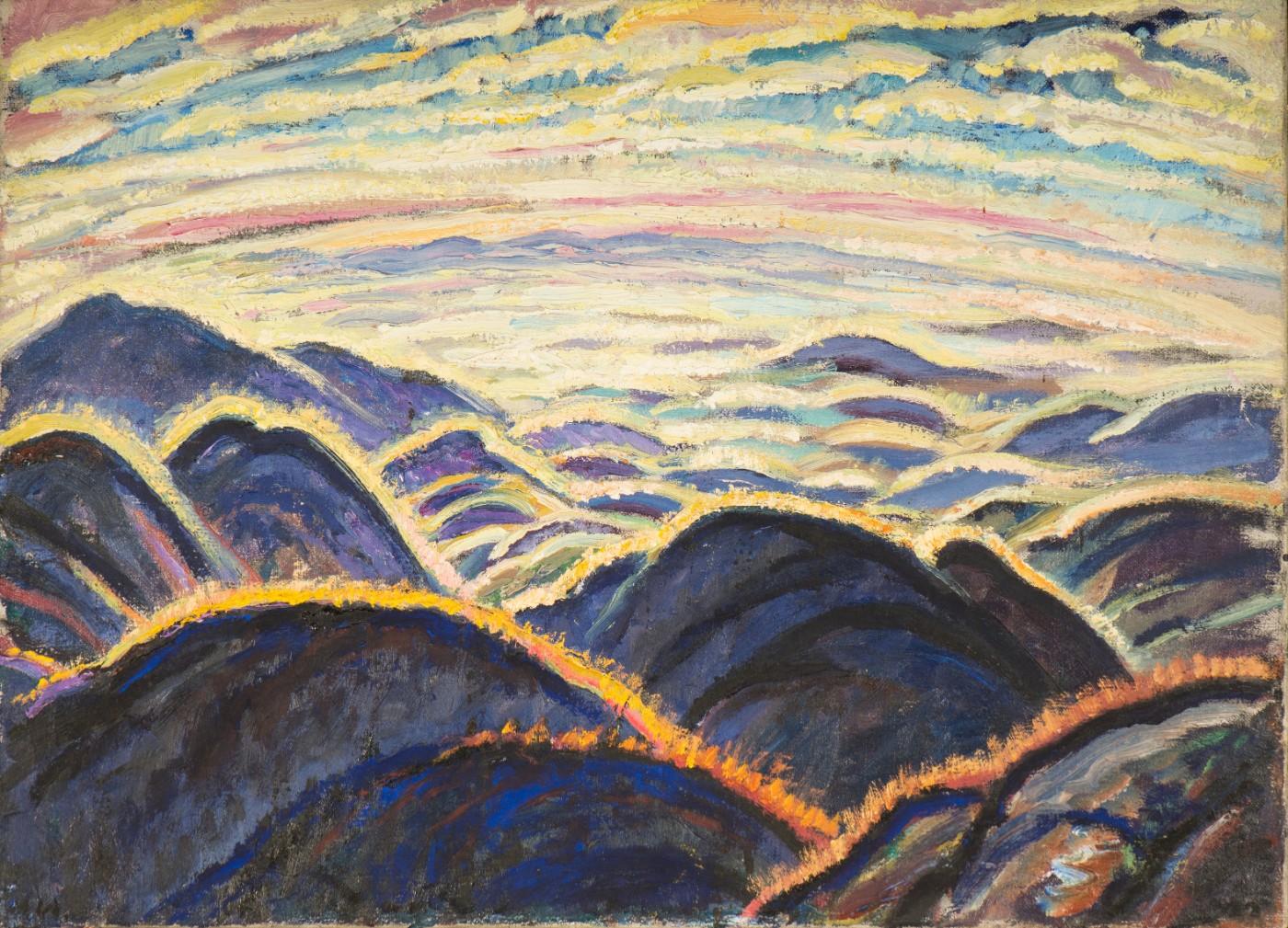

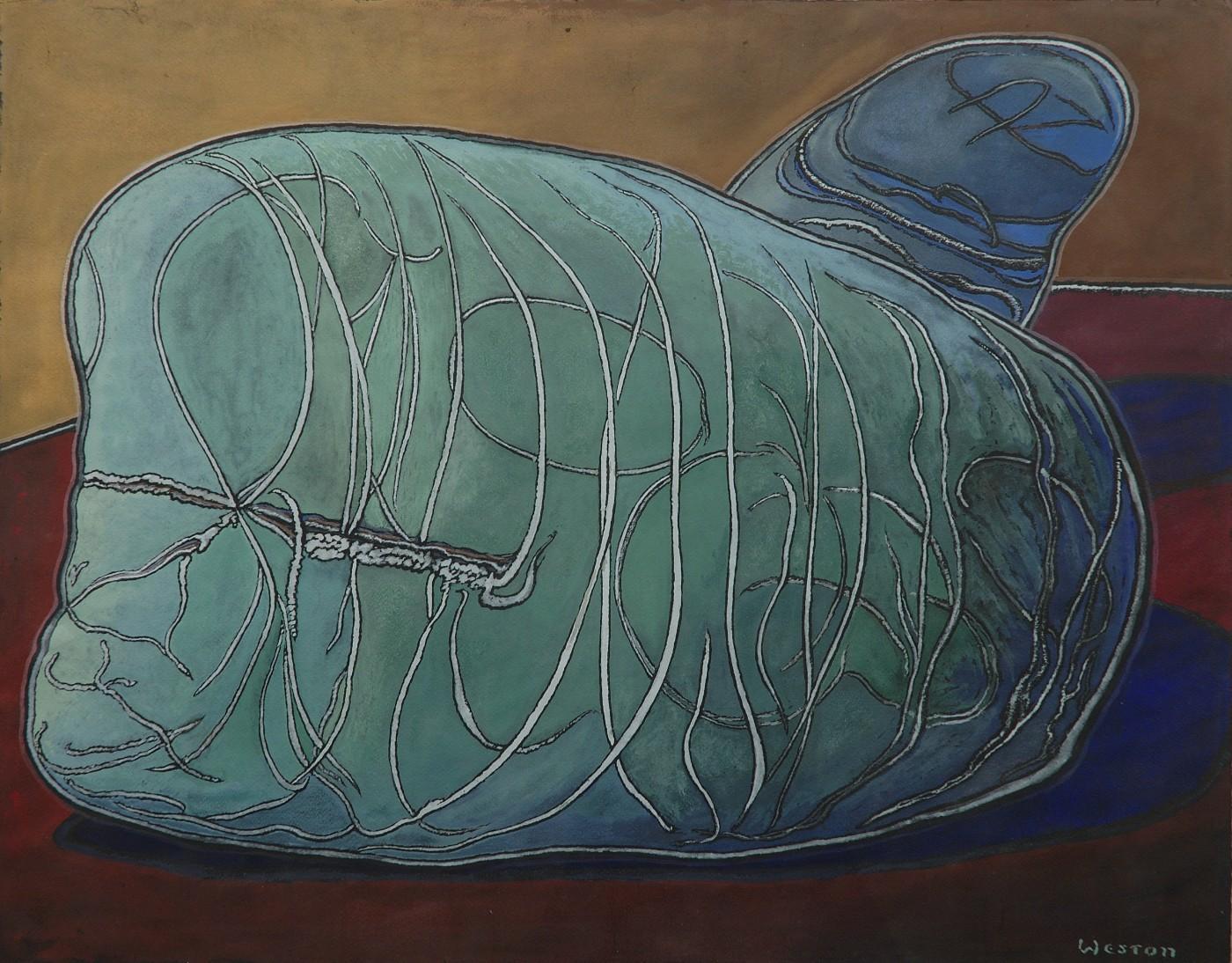

Showcasing two major periods, early landscapes (1920-1923) and the lyrical abstract Stone Series (1968-1973), the exhibition bookends Weston’s life, filling the years in between with excerpts from his diary and letters to his beloved wife Faith Borton whom he married in 1923.

Born into a comfortably middle-class family on Valentines Day, 1894 in Merion, Pennsylvania, Weston’s pleasantly normal childhood changed dramatically when he was struck with polio in 1911. His doctors said he would never walk again. Defying all expectations he not only learned to walk but went on to hike up and down the mountains that became his primary subjects in paint years later. In 1912 he entered Harvard University, majored in fine arts and served as editor of the Harvard Lampoon while contributing artwork and cartoons. Although his bout with polio prevented him from serving in WWI, Weston volunteered with the YMCA, traveling throughout the Middle East working with soldiers in Baghdad to establish a therapeutic art club. The starvation and disease that he encountered in the region had a profound effect on him, inspiring a lifelong commitment to advocating for global food aid. Perhaps Weston sought solace from the horrors he witnessed when he returned to the mountains near Saint Huberts, New York and built a rugged one-room cabin. While living there he painted through the harsh winters from 1920-22, creating his most vital landscapes.