Even though the title suggests that the fascination with the occult, which swept the intellectual circles of Europe and the United States from the late 1800s onwards will play the lion’s share, Otto's book painstakingly details how the Bauhaus was much more than a design-centric school. In it, she details the new ideal of the artist as an engineer, the subtle challenge to traditional masculinity promoted by the liberal mores of the Weimar Republic, and the way women Bauhäuslers were central in shaping the cultural direction of the school. “It’s a magpie movement that brings together many things,” she said.

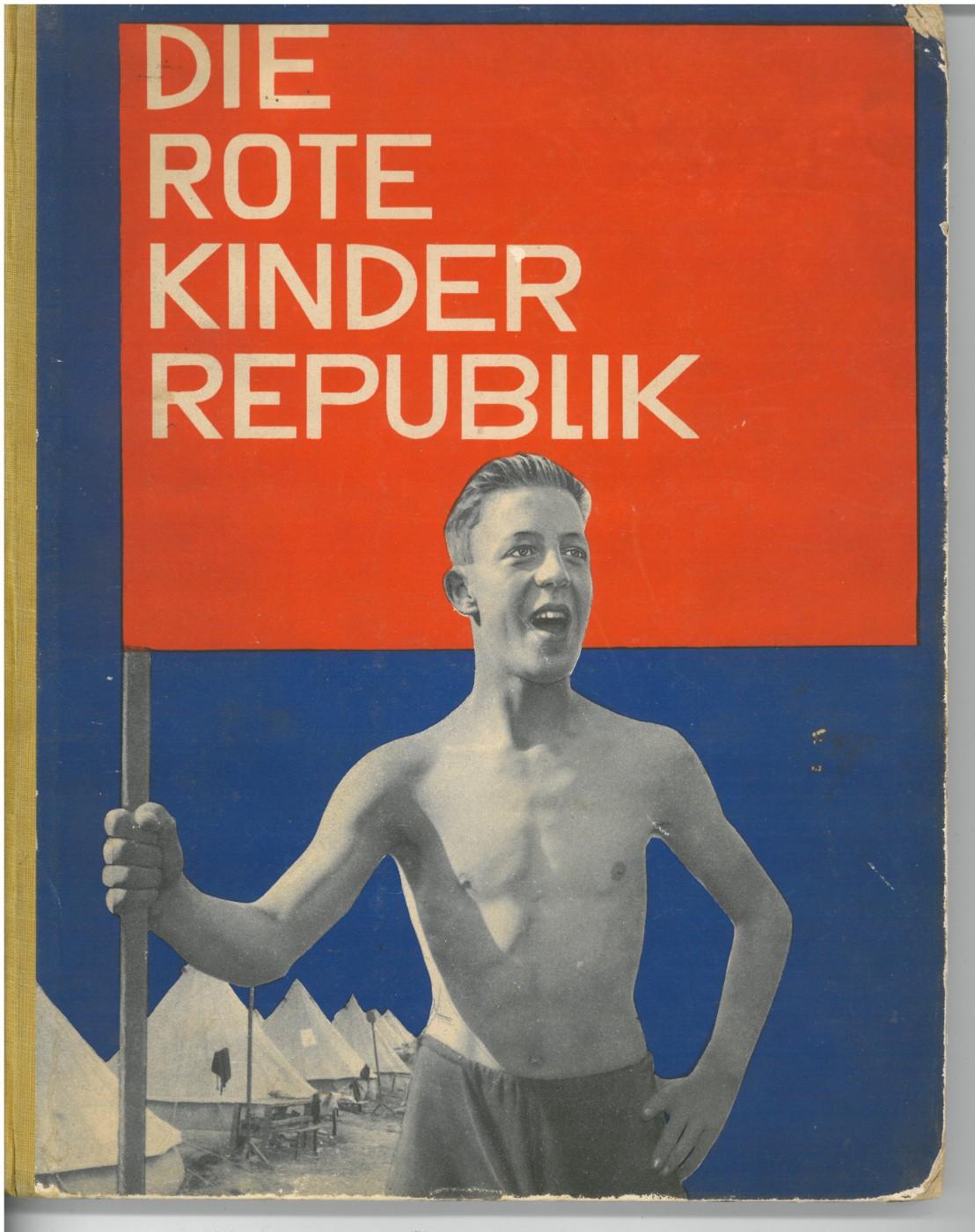

Richard Grune (with Niels Brodersen), cover of The Children’s Red Republic: A Book by Workers’ Children for Workers’ Children (Die Rote Kinderrepublik: ein Buch vonArbeiterkindern für Arbeiterkinder) (Berlin: Arbeiterjungendverlag, 1928). Private collection.

The layperson associates the Bauhaus movement (1919-1933), which turns 100 this year, with architecture comprised of clean lines and with a predominantly male line-up of star personalities, such Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Laszló Moholy Nagy. Needless to say, it is a reductive misconception. “People think it’s an architecture school, and there was no architecture to speak of until 1927,” says art historian Elizabeth Otto, whose book, Haunted Bauhaus, comes out next month.

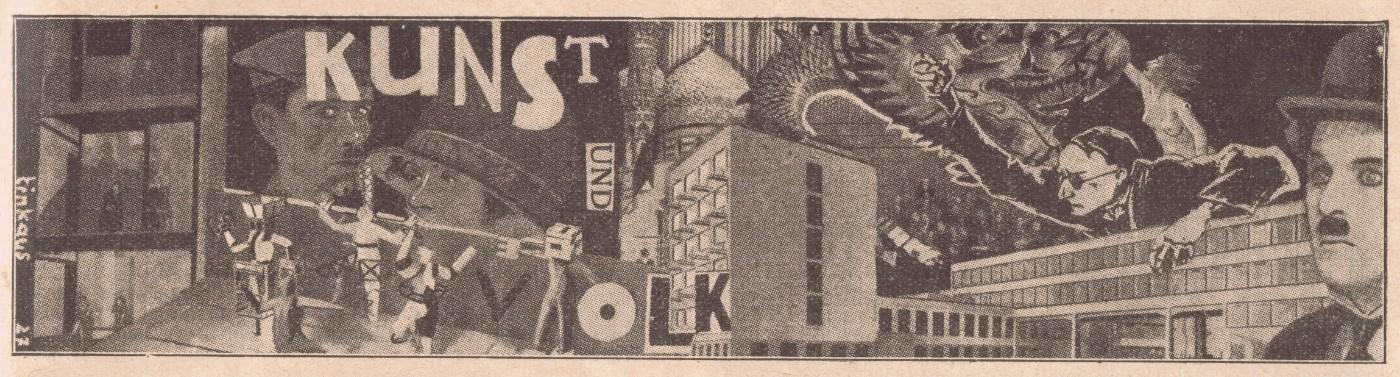

Hermann Trinkaus, Art and the People (Kunst und Volk), page runner for Kulturwille: Monatsblätter für Kultur der Arbeiterschaft 5.9 (Sept. 1928). Private collection.

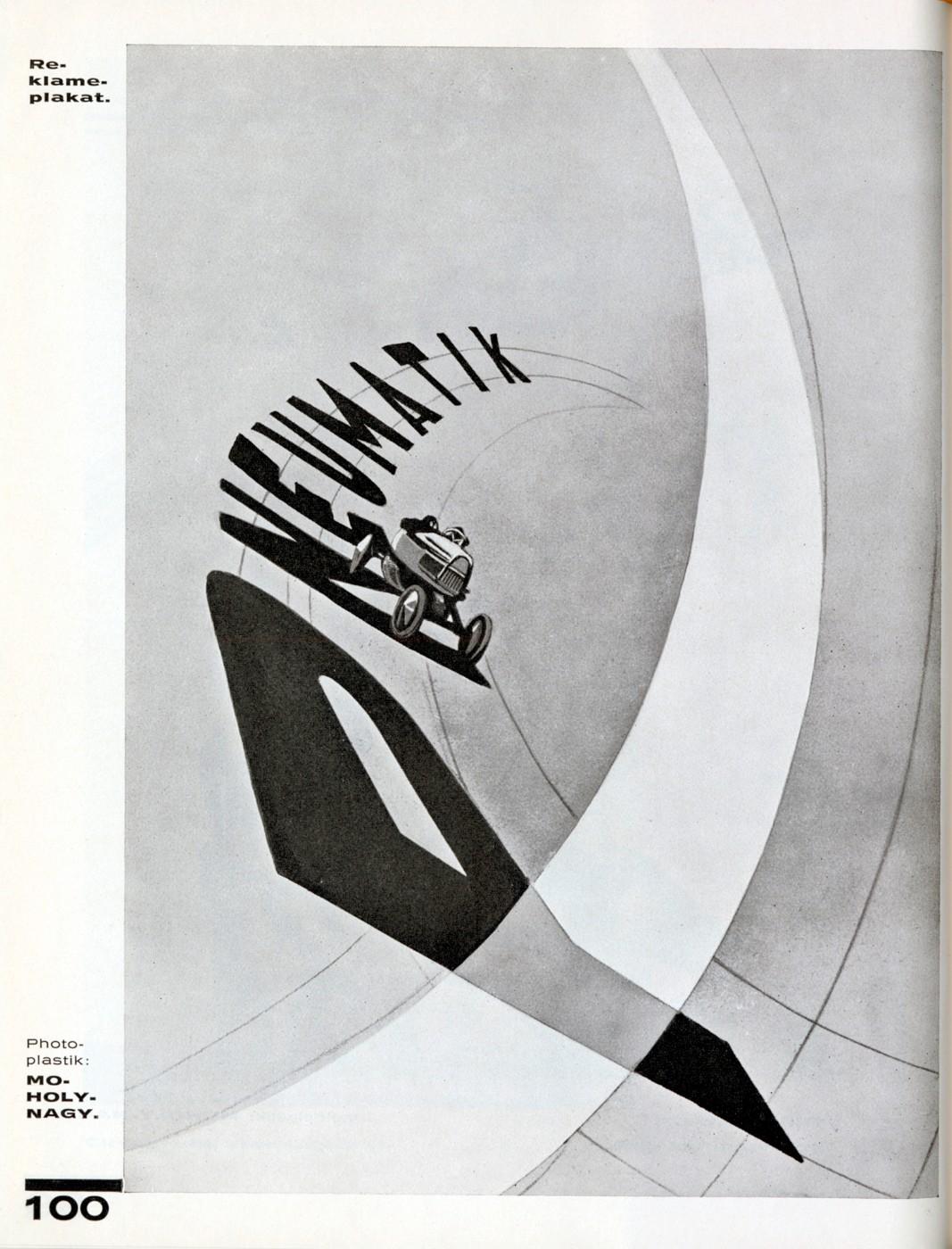

László Moholy-Nagy, Pneumatik: Advertising Poster (Pneumatik: Reklameplakat), 1923, photomontage reproduced in László Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotographie, Film (1925, 1927) [100].

Otto is understanding of the reasons why Bauhaus was often misunderstood. “The history of modern art has been overly systematized: so, this idea of rational and irrational modernism just really took hold, and the Bauhaus became the rational modernism, and all modern history was written to fit that preconceived idea,” she says of the popular misconception. “It also has to do with the intervening years and the people who were promoting the institution: Walter Gropius, above all, but other people too. This idea of purity in art, of it being about aesthetic questions more than anything that has to do with life or things that are more complicated or messy, that was really promoted during the Cold War years.” There are also economic forces behind this reductive interpretation. “Our history really favors narratives of genius, and heroic men can be built up to fit that mold, which then sells really well,” she explains: the art market demands high prices, and one needs a genius ‘scapegoat’ in order to justify the high price tag. “So, the women get written out, the men get talked about as if they were completely infallible.” As for spirituality, it just seemed “too weird.”

“I think that, I’ve been working on this book for at least ten years. These were just always the themes that always came up for me, important to the Bauhaus but often neglected, misunderstood, or written out of history entirely,” says Otto.

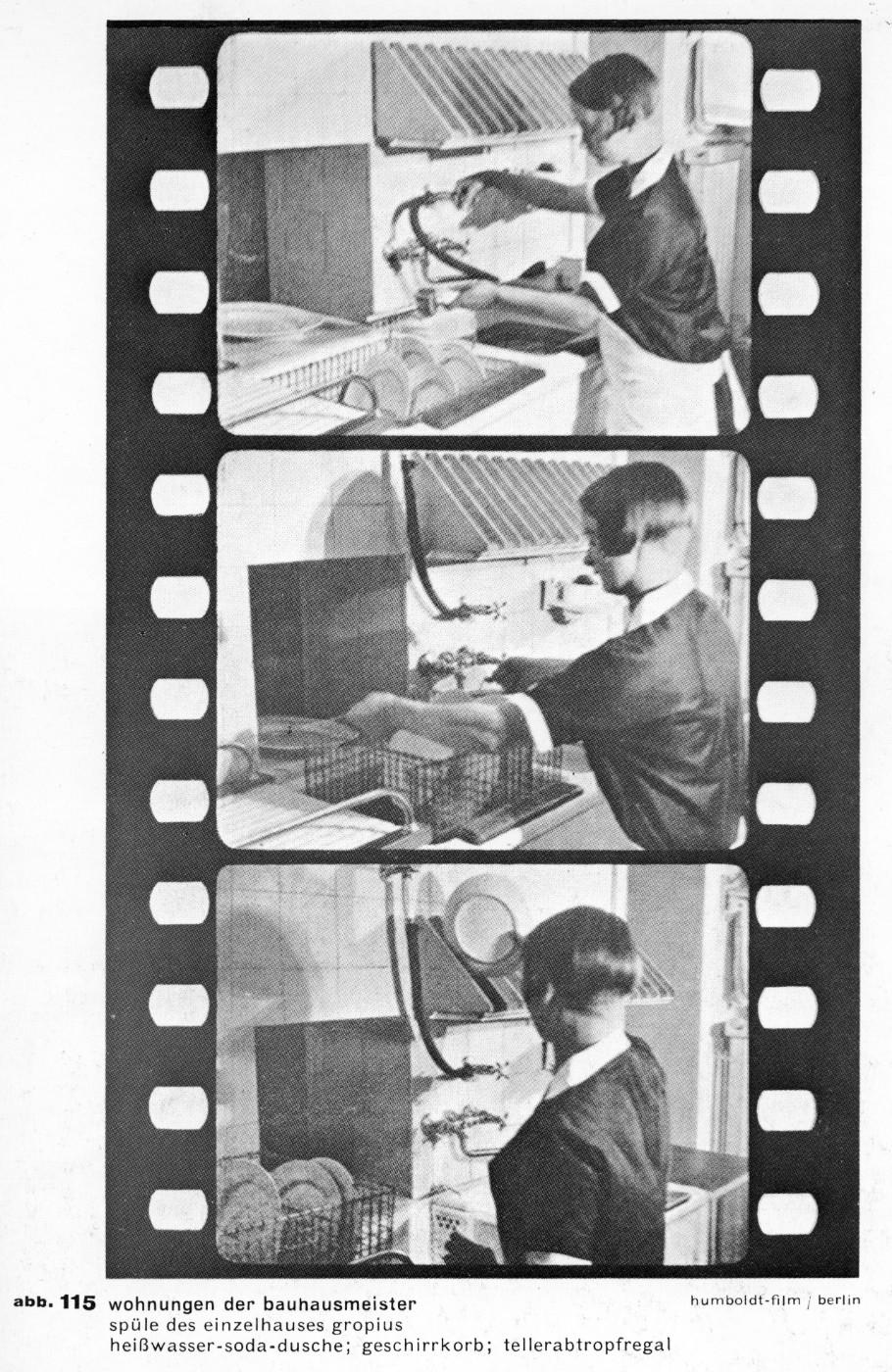

Humboldt Film, Berlin, bauhaus masters houses (wohnungen der bauhausmeister), film stills reproduced in Walter Gropius, Bauhausbauten Dessau (Fulda: Parzeller, 1930) [125]. The caption reads: “kitchen sink of the gropius detached house / warm water–soda–rinse; drainer; plate-drainer shelf."

The case of Gertrud Grunow is emblematic. She was a musician who taught the “theory of harmonization,” which heavily relied on synesthesia. In fact, it aligned the seeing of a color to a feeling or a movement, and, in this scheme, she placed the harmonized self, as the human body, in the middle, as the architecture of a total work of art: by drawing together all these senses, one would be able to perceive how to move in harmony. “She gave her manuscripts of her masterwork to one of her students, and then she passed away. He reworked the manuscript repeatedly, with his own ideas,” says Otto. "The original manuscript was left to rot in a shed in the back garden.” Yet, her importance is undeniable: “If we look at the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition, when the school was first presenting itself to the world, she has the first essay after Gropius. It was a text on her harmonization studies, which every student had to take, and she was the one who routinely made recommendations on whether or not they were spiritually ready to go on to work in a workshop. She was really a determining force.”

“Die Landesfrauenarbeitsschule im Bauhaus” (The State School for Women’s Work/Home Economics), Anhalter Anzei-ger, 35 (Sept. 2, 1933): n.p. (“Heimat” section).

Importantly, in the Bauhaus-fostered visual arts, gender was not touted as part of an artist’s identity. “Bauhaus women were interested in being people, rather than promoting something inherently feminine, especially in Bauhaus context where being too feminine was seen as a potential liability, as it made the school seem less serious,” said Otto. “[Bauhaus women] were pushing towards an identity that did not have a name, an identity of a creative, modern artist who was also female,” said Otto.