Karla Knight: Notes from the Lightship

Andrew Edlin Gallery

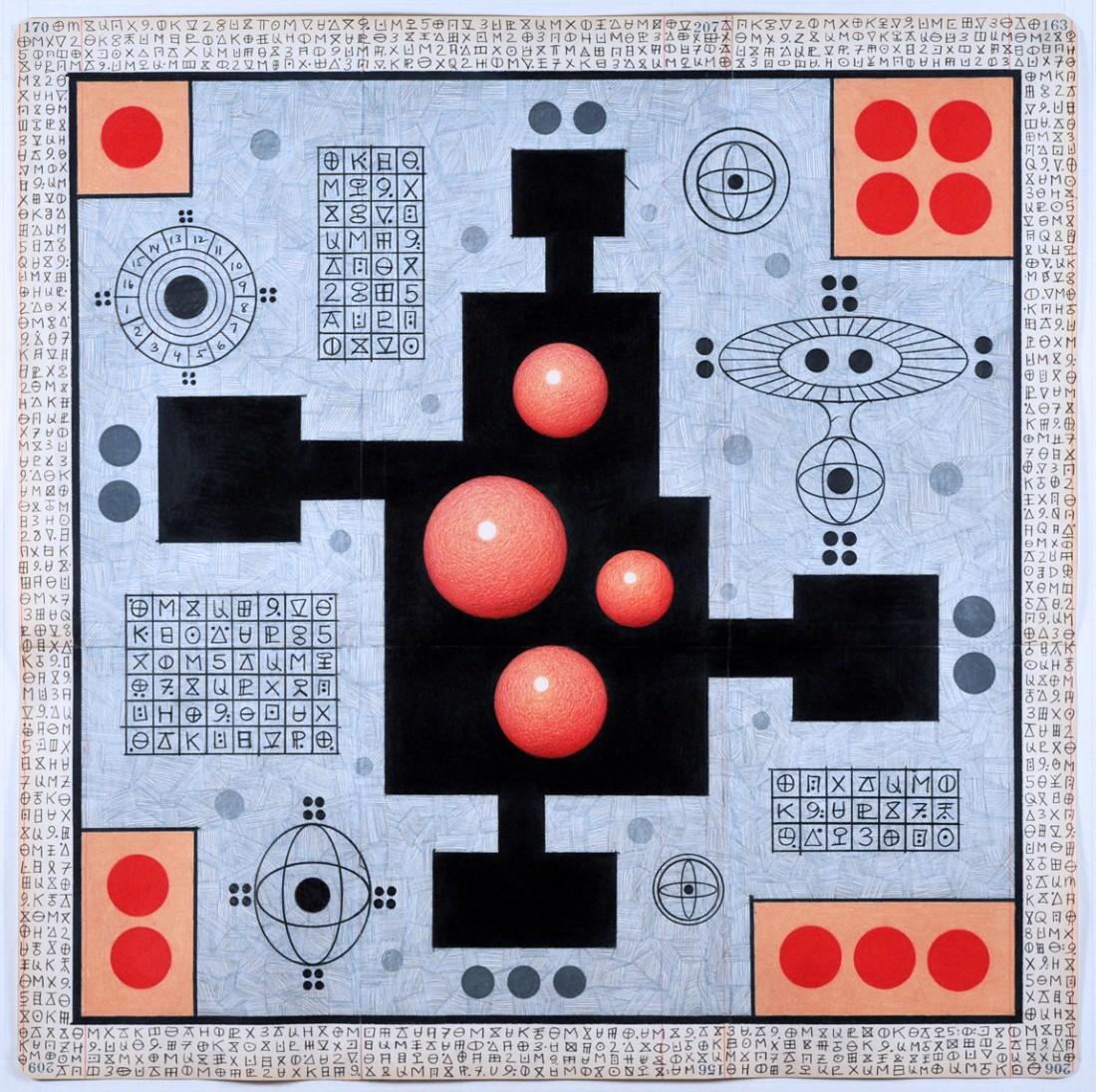

Employing recycled ledger paper as the ground for her drawings, collages and paintings, Karla Knight makes diagrammatic, pseudo-scientific abstractions that utilize a personal hieroglyphic vocabulary, which she’s developed and refined over the past twenty years. Initially inspired by her five-year-old son, who invented his own letters while learning to read and write, Knight mixes her language with colorful graphic signs and symbols, which are both imagined and universal. Reminiscent of computer motherboards and floor plans for houses, shops and airports, her visionary compositions function like spaceships, in which Knight can upload her abstract characters and forms, stylistic references to artists she admires and imagery from her earlier, more surreal, works.

Installation view of Julian Schnabel: The Patch of Blue the Prisoner Calls the Sky at Pace Gallery.

Artists have been working with found objects since the beginnings of modernism, but the meaning implied by the objects that they use and the way that they employ them is always changing. Change, in fact, is one of the main reasons for working with reclaimed materials. Art can change the world—at least from what it was to what it can become.

Rodney McMillian, whose solo at Petzel is one of the exhibitions highlighted in this round-up of New York shows dealing with the transformation of found objects, calls these type of goods “post-consumer,” because after they’ve served their use and become discarded, they enter another system, where artists give them new lives.

In current times, we’re in need of change. The five exhibitions highlighted here offer formulas for renewal in surprisingly inventive ways.

Karla Knight, Spaceship 9, 2017-19.

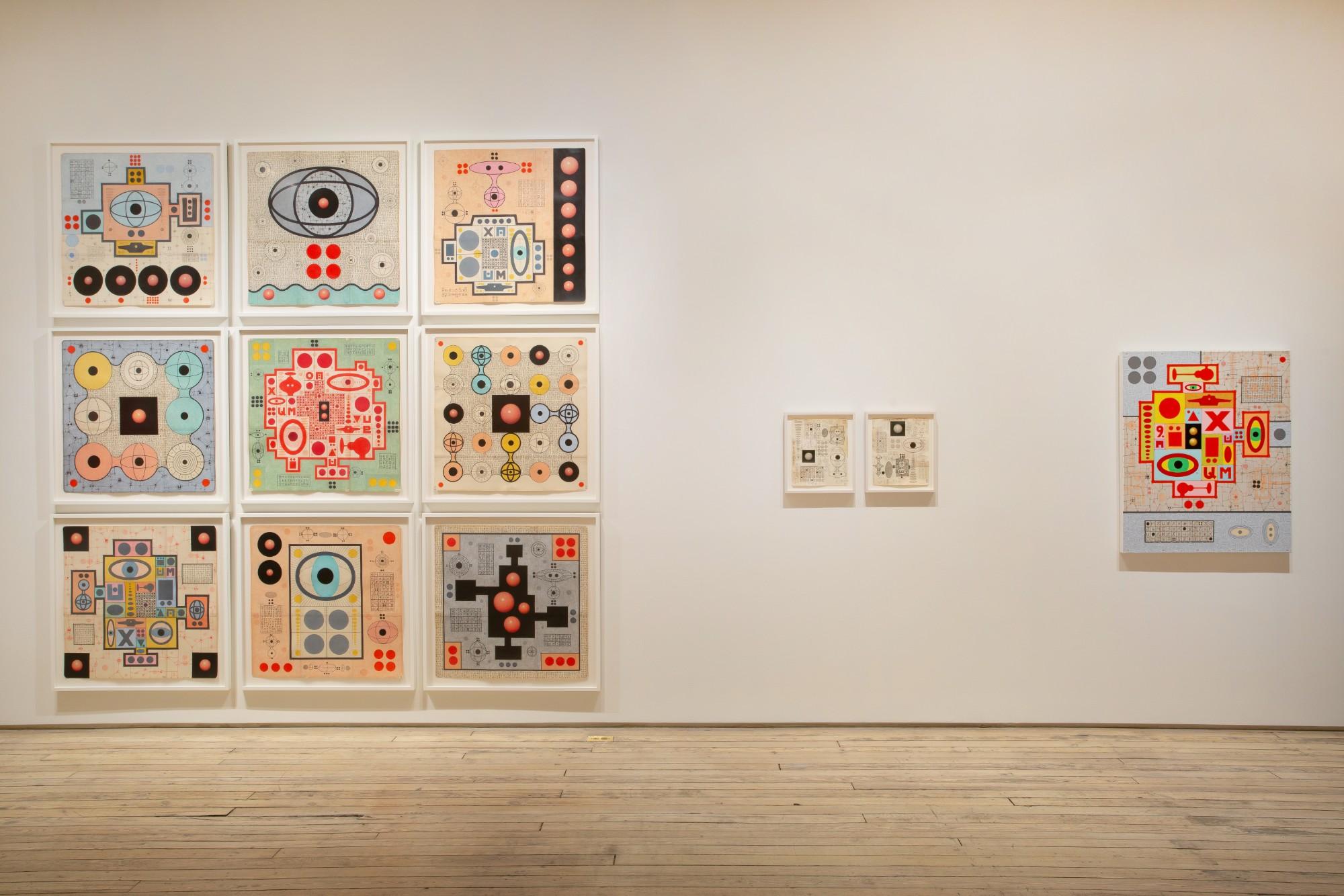

Installation view of Karla Knight: Notes from the Lightship at Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Offering a selection of small- and medium-scale drawings and collages with several larger canvases, Notes from the Lightship is Knight’s first solo show at Andrew Edlin Gallery, which has a history of exhibiting works by both trained and untrained artists. And Knight’s a perfect fit, as her marvelous machinelike imagery relates as much to Alfred Jensen’s lively checkerboard abstractions as it does to Ionel Talpazan’s fascinating drawings of UFOs.

Installation view of Bharti Kher: The Unexpected Freedom of Chaos at Perrotin New York.

Bharti Kher: The Unexpected Freedom of Chaos

Perrotin New York

In her first New York solo show in New York in eight years, New Delhi-based artist Bharti Kher presents new paintings, sculptures and a site-specific installation of her thirty-year project Virus, which seems more poignant now than ever. Known for her use of an abstract language with a narrative undertone, Kher employs breakage in the making of her hybrid mirror paintings, which are smashed with a large hammer and covered with colored bindis (decorative dots that are worn in the middle of the forehead), and her sculptures of found festival figures, which she breaks and reassembles in Dadaistic ways. “I break things to know them,” Kher explained during a walkthrough of her show. “It’s a way to release the possibility of the readymade object."

Bharti Kher, The great seat of learning, 2019.

Consisting of reformulated rectangles in frames and shards displayed on shelves, the mirror paintings are covered with Kher’s uniquely dyed, laser-cut, felt dots so that the cracks in the mirrors reveal a kind of cartography on a monochromatic field. As you look at the mirror, the mirror looks back at you—not just via your reflection, but by way of the bindi, which Hindus consider the proverbial third eye. Kher’s broken clay dolls, which date back to the 1940s and ‘50s, are just as psychologically playful, sitting atop their striking pillars. She chops up the allegorical characters and then organically glues them back together—metaphorically becoming a witness to their own regeneration. And regeneration plays a part in her installation Virus, a nearly invisible spiral made up of 10,000 white bindis mounted on the entry wall. Accompanied by a text documenting change over the past eleven years and forecasting transformative events of the next nineteen, it’s a time-tunnel that takes you into Kher’s world and then releases you to the changing reality of life ahead.

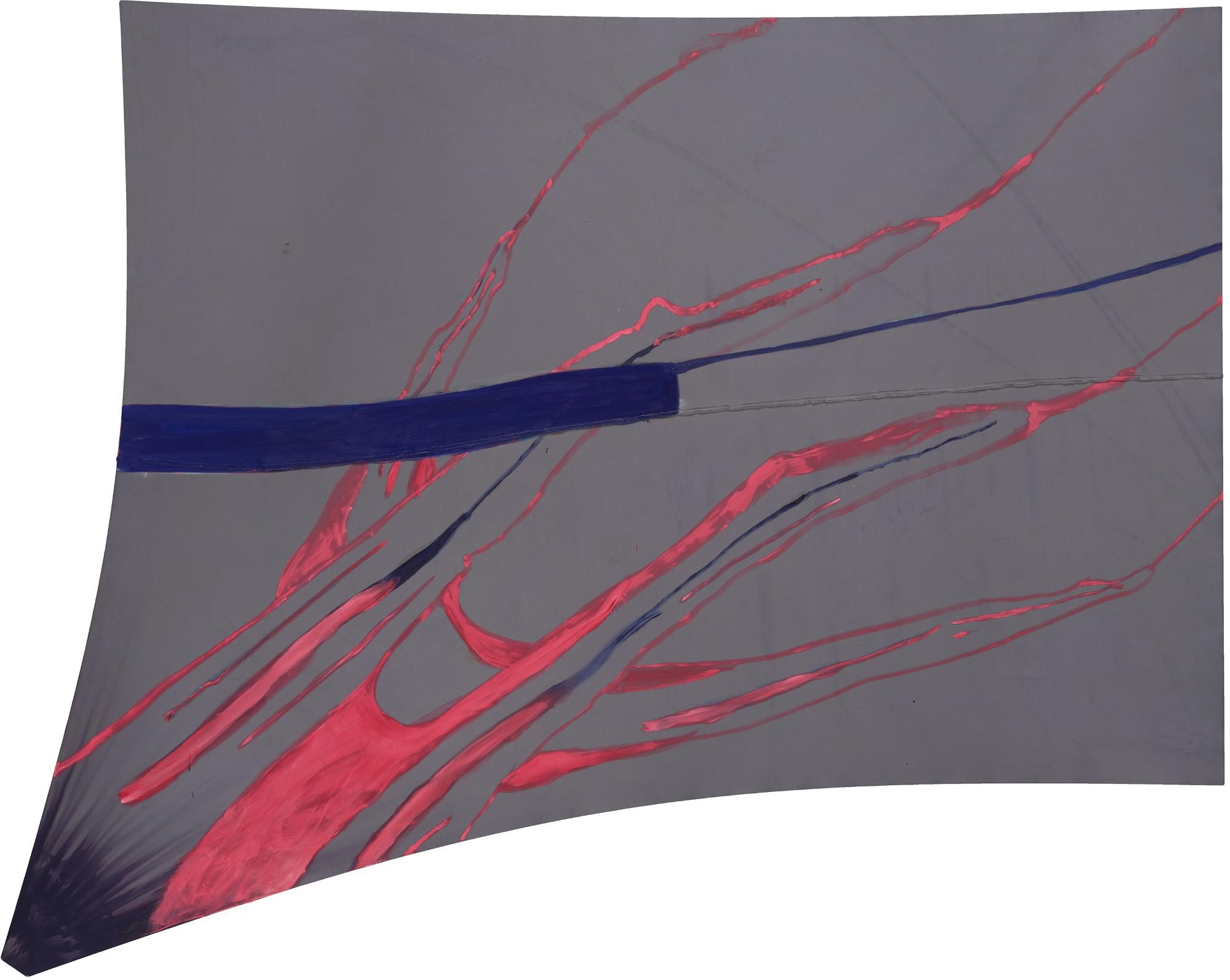

Julian Schnabel, Lagunillas II, 2018.

Julian Schnabel: The Patch of Blue the Prisoner Calls the Sky

Pace

Exhibiting with Pace Gallery since 1984, this show of thirteen paintings from the past two years marks Julian Schnabel’s first exhibition in the gallery’s new Chelsea building, which only opened last fall. Rendered on large recycled cotton coverings that the artist bought right off the roofs of a toy store and a few fruit stands in a rural beach community in Mexico, the weathered abstractions were painted while stretched between palms trees at his Mexican getaway and on the deck and walls of his large outdoor studio in Montauk. “It’s always a kind of an experiment," Schnabel shared during the preview. “What can I use? How can I find or make a mark that will give me a chance to see something else? How will the paint sit on the material? How much do I have to do?”

Some of the largest, irregularly shaped canvases are faded from purple to gray, with seemingly black suns radiating from the corners, where the fabric was tied to poles. Featuring delightfully doodled lines that were intuitively painted with a brush on a long stick, they evoke landmasses that are marked by erosion and intersected by bold trajectories of another nature. The smaller pink canvases, which are more varied in palette and brushwork, fall into two distinct categories: ones that are judiciously painted on faded fabric and others that are expressively executed on sewn together sections of faded and non-faded material, which has been sporadically stained with washes of blue ink. Reminiscent of the artist’s earlier works, they represent a leap into a painterly void, where every detail seems to matter.

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), 2020.

Firelei Báez

James Cohan

In her second solo exhibition at James Cohan since joining the gallery in 2018, Firelei Báez presents a selection of paintings of figures of women, plant life and bodies of water overlaid on reproductions of historical maps, games, and documents printed on canvas. Related to the broader history of the black diaspora, the ground images define the boundaries of the ancient world, trade routes across the Caribbean region and parts of the Americas inhabited by “cannibalistic Indians,” while the overlays represent forces that bring about changes in the ways of thinking about issues of identity and interactions with people of color.

Installation view of Firelei Báez at James Cohan.

The key character in bringing about change is the “ciguapa,” a mythological mountain creature from Dominican folklore. A female trickster, the magical being has blue or brown skin and flowing hair that covers a nude body. Báez imaginatively illustrates her legs surreally merged with lush tropical plant life and trippy washes of color and renders her hair fantastically woven into root-like forms that bloom fresh flora. Informed by an interest in cartography, folklore, feminism and science fiction, Báez’s disruptive ciguapa figures—along with her more sublime portrayals of raging waters—provide thought-provoking perspectives on power and oppression—one that’s meant to help us navigate the past and present, while refashioning the narrative for the future.

Rodney McMillian, Untitled (setting sun), 2019.

Rodney McMillian: Recirculating Goods

Petzel

Rodney McMillian’s initial show with Petzel and the gallery’s first exhibition at it’s new Upper East Side space, Recirculating Goods offers a series of abstract landscapes painted on found blankets, which were sourced from charitable thrift stores and secondhand shops. Purposely pouring and layering latex house paint, purchased from a Home Depot, onto hand-woven bedding, which sometimes still bears a price tag revealing the origin of the economic system where it was circulating, the artist hits on issues of class, race, and gender.

Installation view of Rodney McMillian: Recirculating Goods at Petzel.

In previous, related landscape works, McMillian has envisioned his environments inhabited by Bill Traylor’s hand-drawn figures of sharecroppers and animals, while also referring to the pouring and splattering of the paint like “the spillage of blood.” Granted blankets, too, can allude to the body—and even the pleasures of the bed— but there’s also the implication of an absent human presence in the discarded object and the deserted, painted terrain. Imbued with new lives, these knitted canvases are destined to find a new place in our lives.