Many Vorticist artists and critics were associated with reactionary politics. The movement largely celebrated bellicose masculinity and physical violence, two factors that began to seem deeply unsettling to even its own members during and after the First World War. Historians examining Vorticism during its lifetime and in the following decades noticed how closely aligned the group was with certain iterations of Fascism. This was part of the “point” for many of the group’s members, who believed that war offered a clear path to cleansing Britain of its dull past.

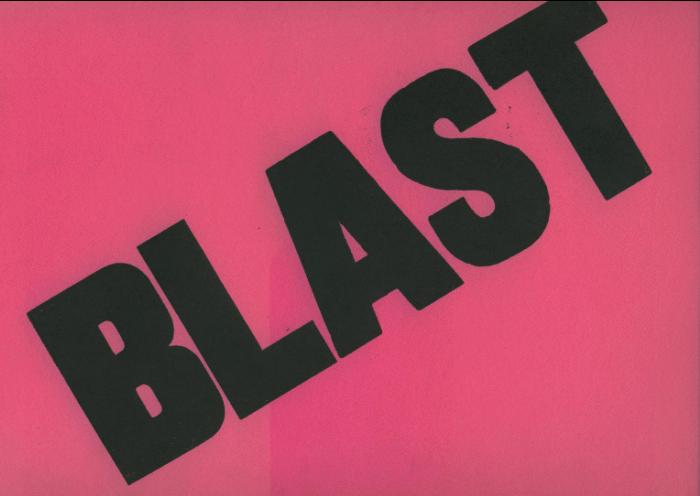

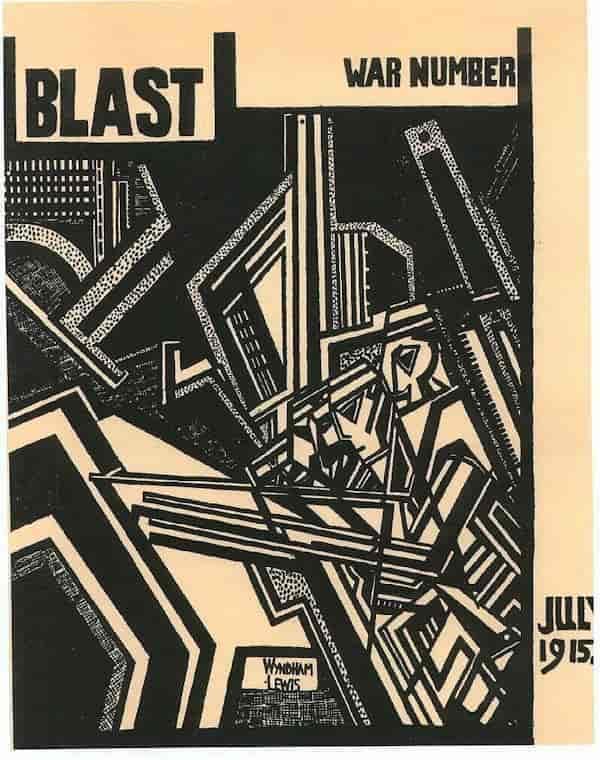

Cover images of Lewis’s Blast magazine give us insight into some of the formal features the group privileged: blocky, hard edges and lines that shoot upward in violent diagonals. Human forms merge with brutal architecture and artillery, erasing any distinction between the organic and mechanical.

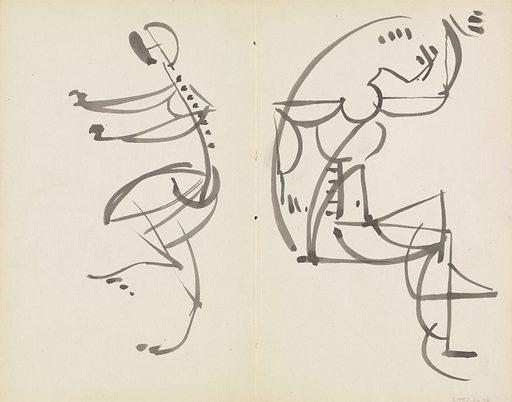

Edward Wadsworth’s later still lifes are crisp, with planes of flat color and meticulously rendered, sharp shapes. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s sketches and drawings of human forms are distinctly robotic, distilled as they are into unsettling lines and unnatural angles. Brzeska’s drawings suggest that humans, animals, and machines might all be the same, with individuality pared down into efficient gestures.