Marco Almaviva, LS Archetipo 1, 2018. Oil colour and literal texture. 53 x 83cm.

Marco Almaviva is an Italian artist born in 1934 in Novi Ligure, Piemonte. His contributions to the contemporary art scene are two new forms of painting, the Tonaltimbrica and the Filoplastica. These pictorial styles were born from the need to answer two fundamental questions: What is the role of art in life? How could a painter overcome the challenge set by Lucio Fontans’s slashes on canvas? The following slideshow explores the development of Almaviva's work and its impact on contemporary art.

1990 Frazione, Olio su tela, cm. 140 x 180

When in 1949, the Argentinian-Italian artist Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) began to slash and pierce the canvas, he created an existential conundrum for painters. By piercing through the essential components of painting—the canvas and its bi-dimensionality—and by adding the third and fourth dimensions of space and time, Fontana threw the art world into chaos. The intent was not only to represent space, but to investigate it beyond the canvas. But what is a painting without a canvas? And, even more crucially perhaps, can there be a painter without a canvas? Amongst those who tried to answer these fundamental questions is Marco Almaviva. Born in 1934 in Novi Ligure, Italy, Almaviva is the son of the sculptor Armando Vassallo, a leading figure of the Italian artistic scene of the early 1900s.

Marco Almaviva, Selva Bassa, 1967. Olio su tela, 150 X 135cm.

Almaviva began his artistic adventure in Milan between the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the ‘60s. The art environment was buzzing: Fontana and his disruption had marked the beginning of Spatialism and artists were now driven by innovation and determined to make their mark. Milan and Venice were the cities where artists would debate, present their works to famous galleries, confront and challenge each other. Almaviva came into contact with some of the most important names of the Italian art scene of the 20th century: Gino Ghiringhelli (1898-1964), Carlo Carrà (1881-1966), and Fontana. These years created in Almaviva the need to pursue his own artistic language, distancing himself from past trends and techniques.

Marco Almaviva, Sunnus, 1979. Olio su tela. 100 X 91 cm

Those years created in Almaviva the need to pursue his own artistic language, distancing himself from past trends and techniques and rejecting the tendency of placing his work under the umbrellas of the Cubist and Pop Art movements. He has always been driven by the search for originality, the need to create an artifact that could go beyond the limits imposed by Fontana and Spatialism. This was not simply an intellectual exercise, but an artistic one: he wanted to create. “When relying on known styles and techniques, our ideas inevitably lose substance.” He remarks, “I was called caparbio (headstrong) and I recognize myself in this definition. [...] I became a painter when painting had been declared dead.” His pursuits brought into being two pictorial styles: the Tonaltimbrica and the Filoplastica.

Marco Almaviva, Yvette, 1979. Olio su tela. 60 X 80 cm

This was a short period in Almaviva’s artistic life, yet an important one. Tonaltimbrica is the melding of two words: tonale (tone) and timbrica (saturation), both referring to the qualities of colors. Almaviva was interested in exploring the violence that characterizes the natural world. His view is that there is nothing idyllic in nature, no supernatural intervention that can aid its understanding or soften its cruelty. How can painting, through its conventional styles and forms, express nature’s battle for survival? Almaviva stripped everything back to the basic elements of tone and saturation. The tone outlines the masses in the background, while the saturated sign is a thread of pure color that marks the shapes and creates the framework of the painting.

Marco Almaviva, Vornio, 1998. Olio su tela, 100 x 130cm.

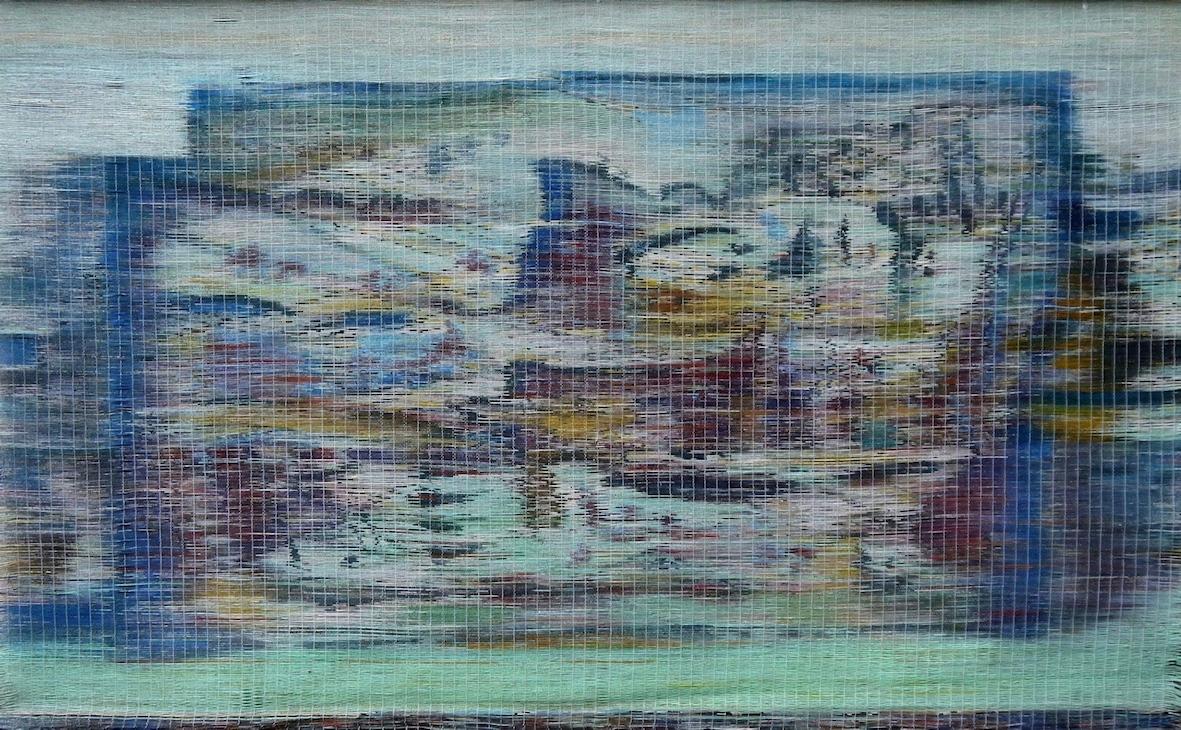

The stark marks of Tonaltimbrica were transformed into soft, sinuous threads that enter in symbiosis with the tonal background of the painting. The result is that the saturation of the thread is subjected to the variations of the tone. In turn, the tonal base is modified by the immersion of the threads. Later on, the painted thread—the element that creates the canvas—becomes an integral part of the canvas itself. It therefore preexists the canvas and does not rely on it for its existence.

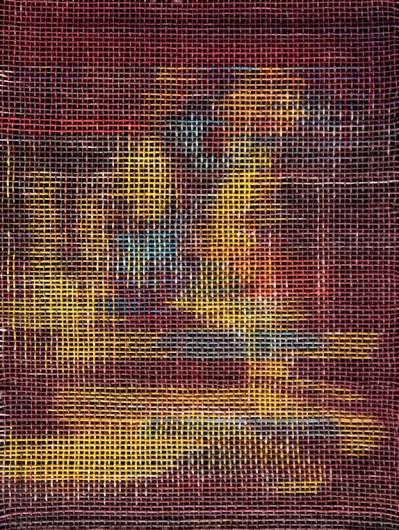

Marco Almaviva, Rectoverso III, 2021. Oil colour and literl texture, 25 x 19 cm

The most representative and groundbreaking work in Almaviva’s catalog is arguably Rectoverso, created between 2019 and 2020. As Almaviva’s research was sparked by Fontana’s destruction of the canvas, it was necessary to address the problem of a canvas-less painting. By using colored threads weaved together, Almaviva was able to create a painting that goes beyond its traditional definition. It can therefore be said that Rectoverso is the first example of a painting without a canvas. Moreover, the front and the back of Rectoverso are the same, overcoming the issue of the unidimensionality of painting on a traditional canvas. Almaviva is indeed painting beyond flatness.

Marco Almaviva, LS Archetipo 1, 2018. Oil colour and literal texture, 53 x 83 cm

When asked about today's art world, Almaviva is critical. While he recognizes that progress has been made since the 1970s, he warns against an illusory democratization of art. In his opinion, there has been a democratization of the personal intentions of those who want to make art: everyone can do it. Yet, what is recognized as art is still decided and defined by the institutions. The distance between those who “have made it” and those on the fringes has therefore widened. While this analysis can appear full of pessimism, Almaviva remains caparbio and warns to not let others decide whether your art is worthy as it could end up being a long and sometimes fruitless wait. This is to say, borrowing the words of another artist, David Bowie, “Never play for the audience.”

Caterina Bellinetti

Dr. Caterina Bellinetti is an art historian specialised in photography and Chinese visual propaganda and culture.