Considered one of the mid-twentieth century’s most impactful sculptors, Barbara Hepworth was a pioneer of piercing holes into sculptures, alongside Henry Moore, a fellow student from the Leeds School of Art. As early as the 1930s Hepworth was making modernist abstract pieces. With her second husband, British abstract painter Ben Nicholson, she traveled to Paris, where they visited the studios of pioneering sculptors Constantin Brancusi and Jean Arp, and painters Georges Braque, Piet Mondrian, and Pablo Picasso. At this time, Nicholson painted rectilinear compositions, influenced by Mondrian and also Hepworth: his abstract relief pieces, often painted in white, have much in common with Hepworth's white sculptures in alabaster and marble of the same period.

Sam and Mary Ann Scherr, early 1970s.

By exploring three modern artist-designer couples of the twentieth century, we revisit two timeless art debates: the intersection between design and art, and art history as more than a solitary line of predominantly male geniuses. From English abstract artists Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson in the 1930s; American designers Mary Ann and Sam Scherr working in the years following World War II; to Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins collaborating in the 1960s, London. These artist couples had a creative impact on each other while following their own individual interests, as well as working in different media, from painting and sculpture, graphic and industrial design, to jewelry making.

Barbara Hepworth, Pelagos, 1946.

Ben Nicholson, Relief, 1934. Oil on a carved mahogany panel.

After the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the couple moved from London to the seaside town of St Ives, Cornwall. With three children to support, Nicholson abandoned his abstract compositions and returned to painting landscapes, featuring St Ives Bay and its harbor. Hepworth shared his affinities with the seaside landscape, as seen in the wave-like curves of the pierced sculpture Pelagos (1946). Meaning ‘sea’ in Greek, Pelagos was inspired by the bay at St Ives, where two stretches of land surround the sea on either side. Nicholson and Hepworth divorced in 1951, but they remained key figures in the development of the artists’ colony in St Ives, where Hepworth’s art studio and garden is now a public museum managed by the Tate gallery.

Barbara Hepworth's Studio Garden in St Ives

Mary Ann and Sam Scherr met while studying at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and started dating at the end of World War II. During the economic boom after the war, they both became designers at major automobile companies: Sam at General Motors and Mary Ann at Ford in Michigan. By 1947, the couple had married and opened their own industrial, product, and graphic design firm in their hometown Akron, Ohio.

For three decades, Scherr & McDermott served multiple corporations, designing successful household products such as the Dominion Oven-Broiler, described as “four appliances in one” (it baked, roasted, broiled, and toasted). The firm also gained international recognition through the US government’s contracts for product development in Korea, Japan, and South America.

The Scherrs’ Industrial Design display at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design, Raleigh, NC.

In 1949 the Scherrs had their first child, Randy, so Mary Ann worked part-time from home, designing rubber toys and a nursery rhyme cookie jar series which became famous years later as part of Andy Warhol’s collection. She also took her first classes in metalwork and gained immediate recognition for her jewelry designs. Their son Randy claims that Mary Ann and Sam were indeed the most creative people he has ever met. “They were always doing creative things, round the clock. And there was always artistic space in the house.”

Mary Ann Scherr, Ovals necklace and earrings, c. 1980. Private Collection, Raleigh, NC.

At the peak of the couple’s careers in the late 1970s, Sam was President of the American Crafts Council, and Mary Ann worked as Chair of the Product Design Department at Parsons in New York City. In parallel to their full-time jobs, they also embarked on entrepreneurial ventures, from the independent production of anodized titanium jewelry to marketing limited editions of their designs under the label “The Scherr Collection.”

Although neither of them formally studied jewelry design, British modern designers David Watkins and his life-long partner Wendy Ramshaw pushed the boundaries of jewelry in the early 1960s. The couple first collaborated on “Optik,” Op Art-inspired jewelry made from screen-printed Perspex, alongside self-assembly paper jewelry, which caught the attention of the media after the model Twiggy was photographed wearing their pyramid-shaped paper earrings. While Watkins and Ramshaw embarked on their own independent careers as studio jewelers after the 1970s, they revisited the “flat pack” paper jewelry in 2000 with their book The Paper Jewelry Collection: Easy To Wear and Ready To Make Pop Out Artwear.

Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins, The Paper Jewelry Collection, 2000. Thames & Hudson

Ramshaw’s revolutionary and artistic designs include her seminal Picasso’s Ladies series. For a period of over ten years, she made sixty-six individual jewels that responded to Picasso’s depictions of the women in his life. However, Requiem Necklace for Guernica is not representative of a lover or muse, but of Picasso’s mural after the German bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in the north of Spain. As Ramshaw herself explained, this piece is a “universal requiem not only for the women of Guernica but for all women.” A delicate web of wires is hung in disorder within a brass frame, with garnets that signify the drops of blood shed in the war.

Wendy Ramshaw at work creating Requiem in her studio, London, June 1998.

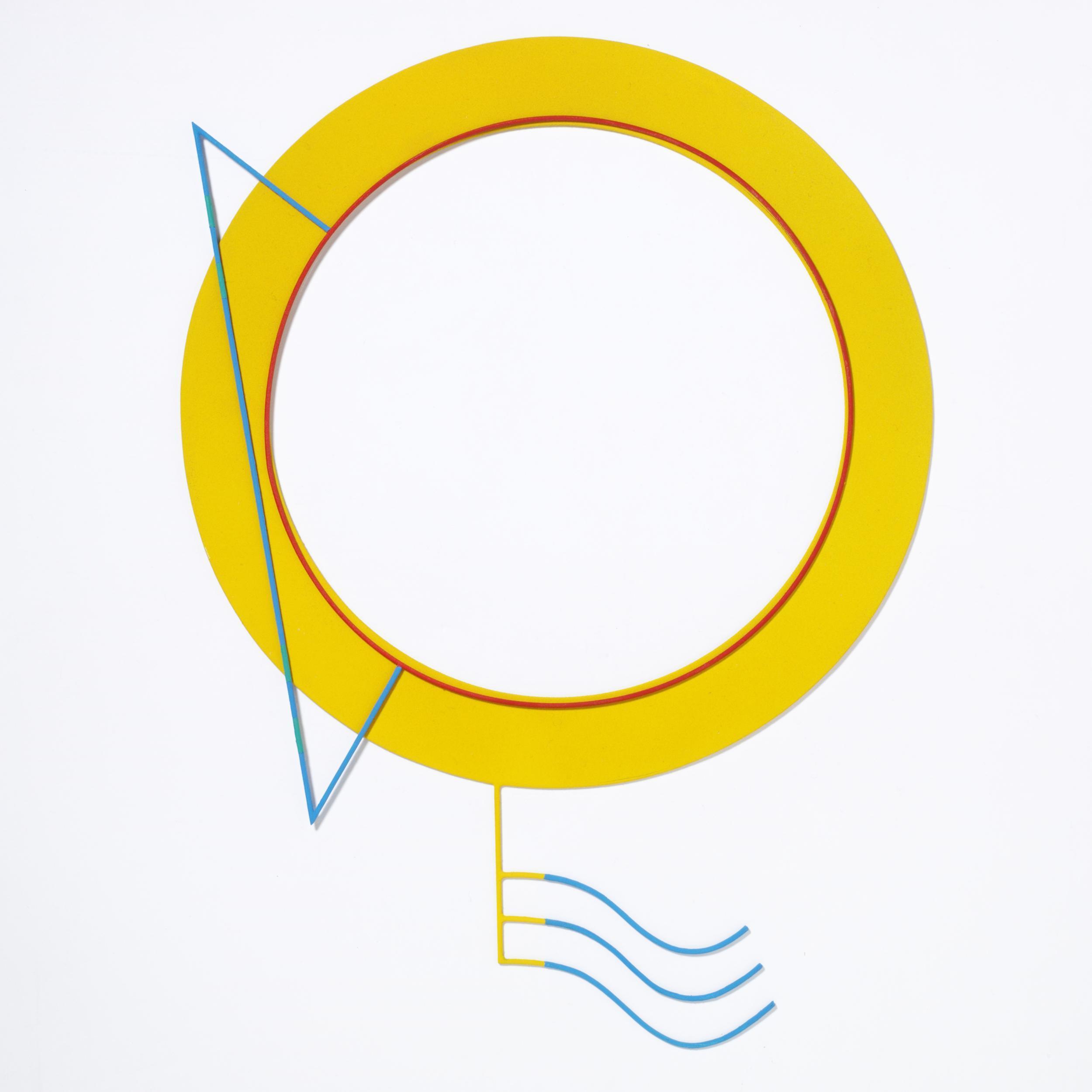

Both Ramshaw and Watkins explored a wide range of inexpensive and unusual materials in their modernist designs, though Watkins’ jewelry is sculptural in a different way. His Wing-Wave 2 neckpiece is a good example of his minimalist and structured work. His music and sculpture backgrounds reunite in this jewel of abstract, yet universal forms, rhythmic lines, vibrant colors, and innovative synthetic material.

David Watkins, Wing-Wave 2 Neckpiece, 1983. Neoprene-coated steel and wood.