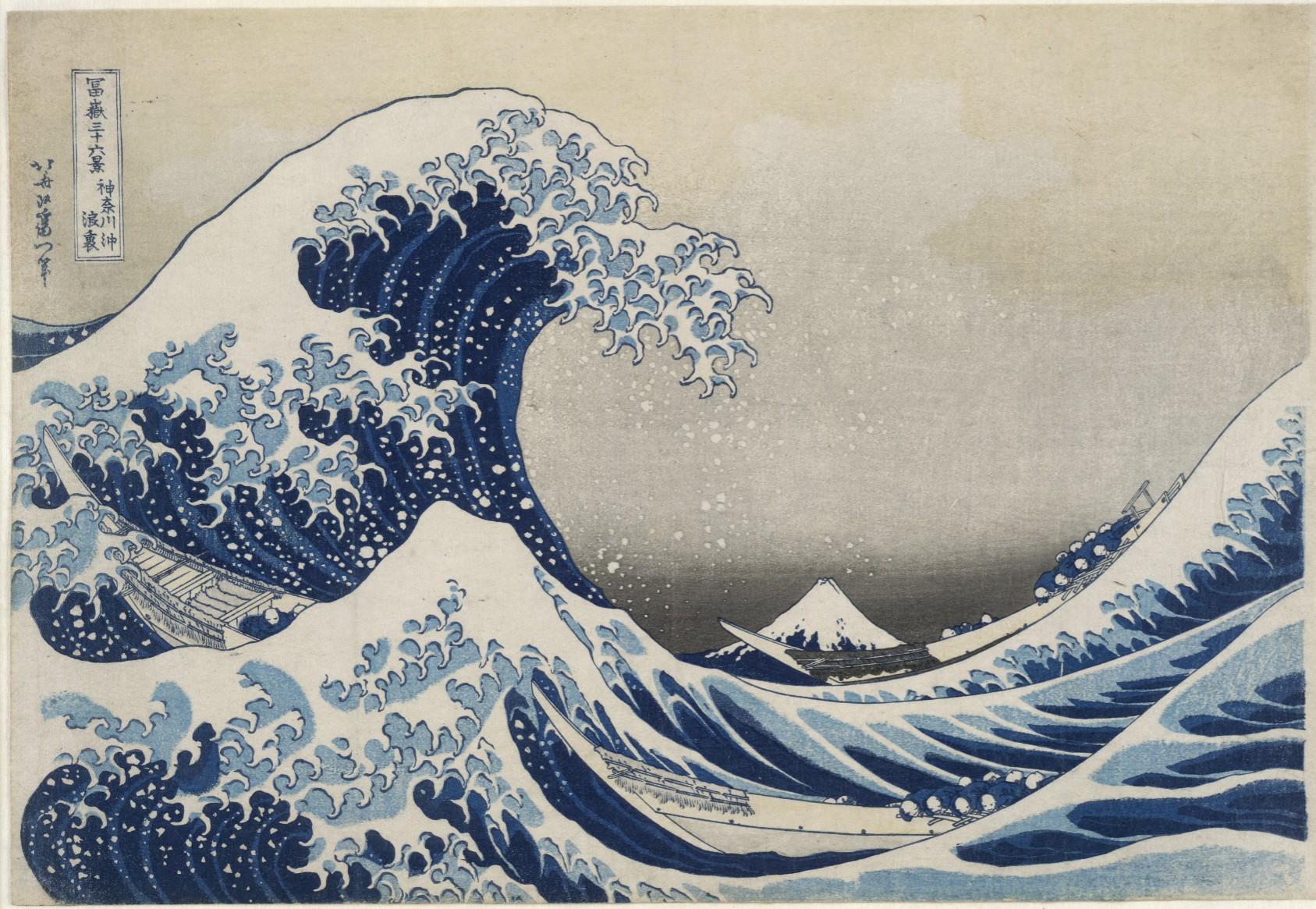

Japanese woodblock prints heavily influenced the Art Nouveau approach to natural form. Though nature was already of interest to Western artists—as it represented the opposite of their ever-growing, industrialized cities—the flat, floral, and curvilinear designs of this print medium proved deeply inspirational. And, as trading relationships with Japan had only recently been established, they were new to most westerners.

Alphonse Mucha, (detail) poster for the publishing house of F. Champenois, 1897. Color lithograph.

Art Nouveau dominated much of the Western art and design worlds from the 1880s up to the start of World War I. The style was inspired by nature, spurred on by the Arts and Crafts movement, and served as a fundamental reaction against Industrialization.

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1830-32. Woodblock print.

René Lalique, Corsage Ornament, 1903-05. Gold with en ronde bosse, plique à jour and champlevé enamel, cabochon rubies, facetted and cabochon peridots.

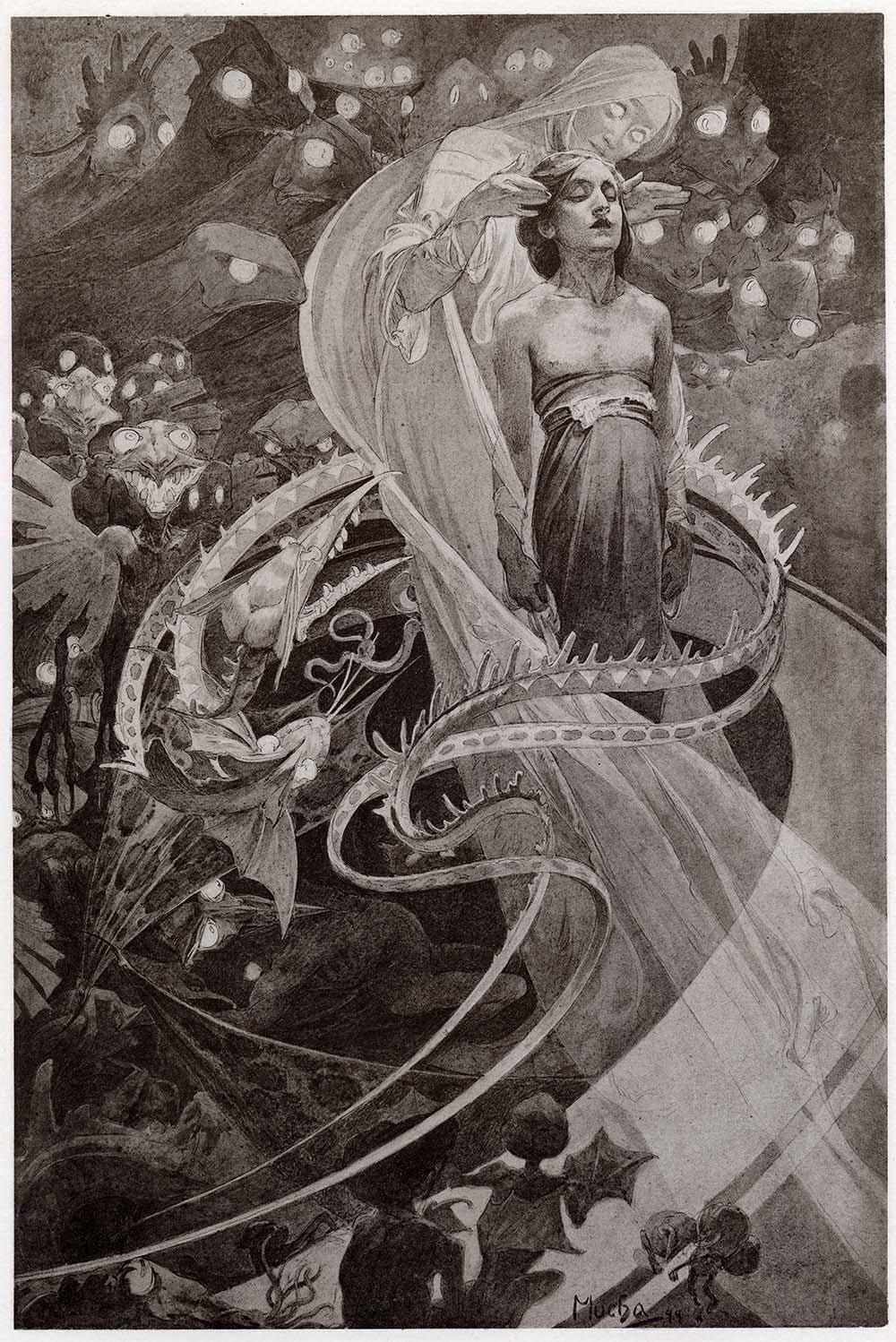

Alphonse Mucha, a Czech artist who lived in Paris during this stylistic period, created some of the most well-renowned Art Nouveau images. Though he primarily created theatrical posters, Mucha—in true spirit of the style—also designed jewelry, fans, commercial packaging, and interior spaces. One can easily spot an Art Nouveau staple—the "Whiplash Curve," often an ornate S-curve—in Mucha's work.

Alphonse Mucha, Seventh allegorical page from Le Pater (an illustrated edition of the Lord's Prayer), 1899.

Art Nouveau designers constantly strove to create a gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. Determined to smash down the barriers between fine art and craft—and to bring art into everyday life—the style and principles of Art Nouveau were applied to almost everything, including glass-covered, Parisian metro entrances.

Hector Guimard, "dragonfly" Édicule metro entrance, 1900-13. Abbesses, Paris.

The city of Barcelona is bedecked with some of the most beautiful examples of Art Nouveau architecture—termed Catalan Modernism within the region. Many of these monumental artworks were designed by Antoni Gaudí. This includes the iconic, albeit yet to be completed, Sagrada Família. The creative design of the church is such that every structure has two purposes—one of function, one of design. This is easy to see in the interior columns, for example, which are topped with branches in order to resemble massive trees.