Despite the well-known practices of these larger-than-life names, it is not uncommon for individuals—both entrenched in the art world and entirely outside of it—to find this artistic outsourcing hard to reconcile with. Many seem to feel it is just too similar to mass-production, a process that does seem antithetical to the concepts of the artistic genius and the value placed on the hand of the artist. And yet, several of the aforementioned contemporary artists embraced this stigmatized association, making it a part of their art’s larger meaning—something we will explore in more depth towards the end of this story.

Like most man-made categories, the classification of an artist is not as concrete as one may think. Specific art makers were not seen as the “artists" we know today until the Renaissance. Before this, artmakers were thought of as artisans. Like bakers and blacksmiths, they were expected to work in tandem with others—to be clear, this is something artists did not stop doing. Nevertheless, public perception shifted and the identity of individual artists began to matter in a consequential way.

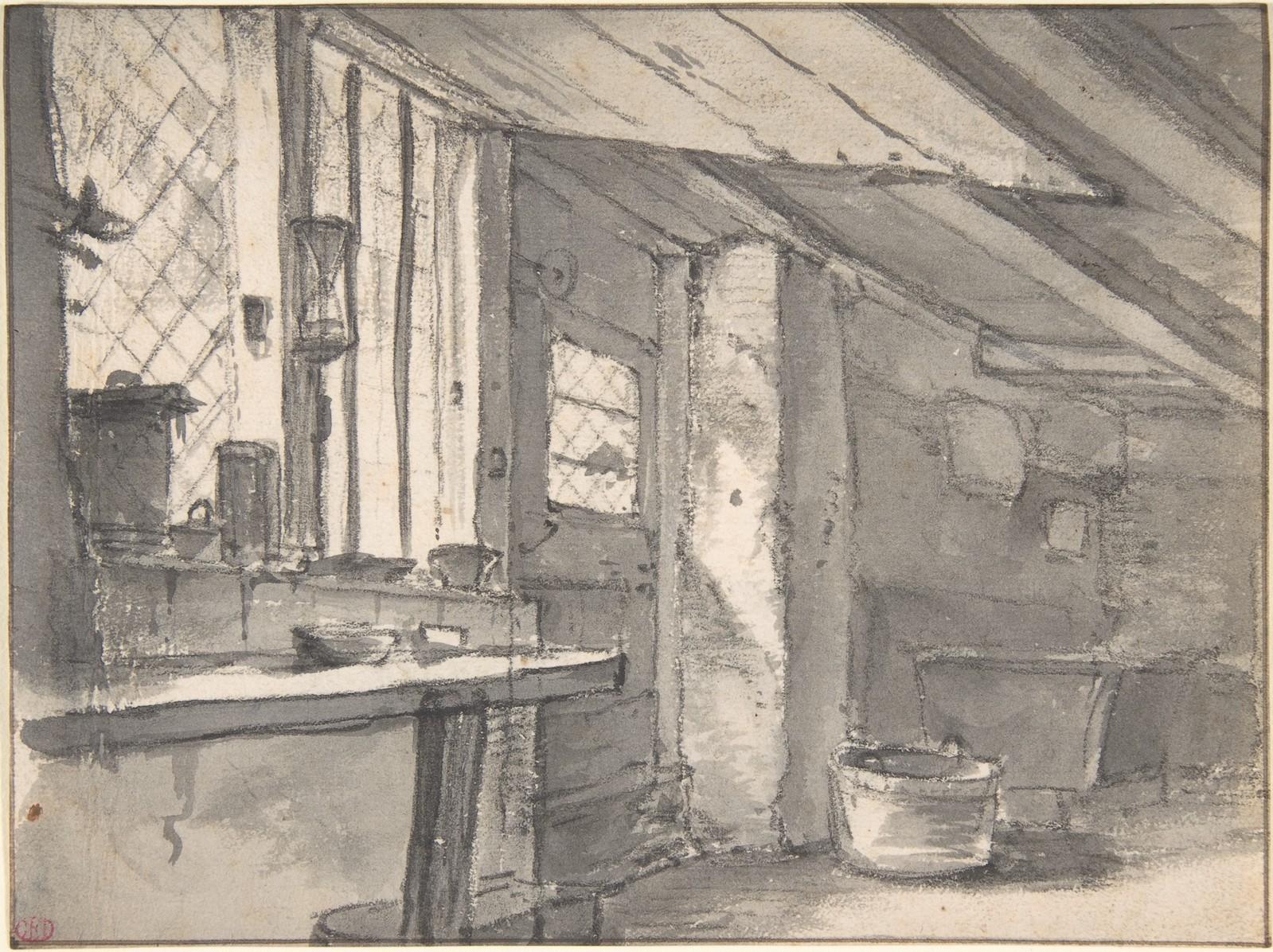

Interestingly, our modern concept of the artist actually came about around the same time as the advent of artist workshops as we know them. The workshops of the Renaissance often served as a training ground for young apprentices who would start with menial tasks in service of the head artist. This work was done with the aim of eventual promotion to an assistant role, in which one would be trusted with more important jobs such as finishing masterworks. Through these tasks, young artists hoped to one day establish themselves enough to create valuable pieces under their own names.