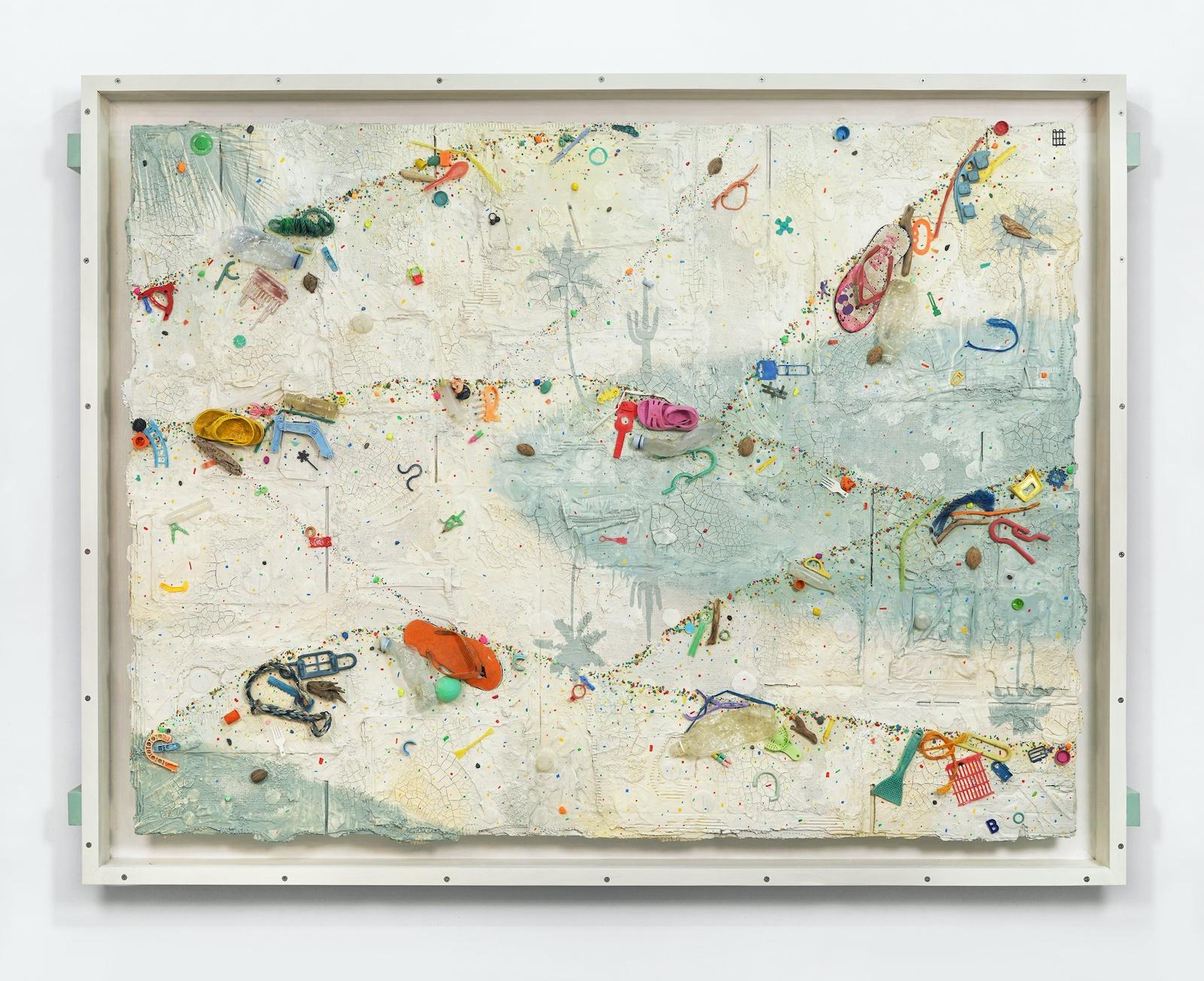

Following recent surveys of his works at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery in London and New York’s FLAG Art Foundation in 2017, Bickerton began his experimentation with the beach trash and has since developed a series of works that he calls Flotsam Paintings. Visually poetic, the paintings playfully feature bits of plastic, rubber, metal, and rope floating on a painted surface of canvas and cardboard. Arranged in an earth and sky binary that echoes the settings in which the artist discovered the discarded items, the paintings objectively comment on the realities of the world without being judgmental.

“It would be a mistake to assume these works are bemoaning the destruction of our home planet,” Bickerton told writer and cartoonist Anthony Haden-Guest in a recent Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art conversation. “I do not think of myself as an environmentalist, as being an environmentalist is to labor under the assumption that you are preserving the planet for human habitation. We as a species cannot destroy the planet, it is ever resilient and adaptive, and far bigger than us, but what we are certainly capable of is destroying its ability to support us as a species.”

Seeing beauty in the ocean-borne trash, Bickerton arranges it both randomly and strategically in colorful visual sentences and spirited groupings across his painted picture planes. Inspired by the surreal landscapes of Joan Miró and Milton Avery abstract seascapes, Bickerton composes hybrid paintings, displayed in handcrafted, crate-like frames, that speak to our times. The canvas Round Cloud mixes flattened flip-flops, plastic forks and combs, discarded cigarette lighters and synthetic drink bottles, and a toy soldier with other debris in a cloud-sky-water-beach terrain to form a dreamlike narrative.