“I was astonished when I came to America, in 1962, how few flowers people had in their gardens. Flowers were not too terribly important, but now horticulture is big business and very exciting.”

Overy cultivated her interest in drawing flowers. But when she took an art class at DBG and it didn’t teach what she wanted to learn, she created her own curriculum. “People wanted to learn to draw the flowers at Denver Botanic Gardens. I ran these classes, and much to my amazement they filled immediately. People were thrilled. They didn’t know how to look. They didn’t know about pencils or papers. They were not taught. There was a real hunger.”

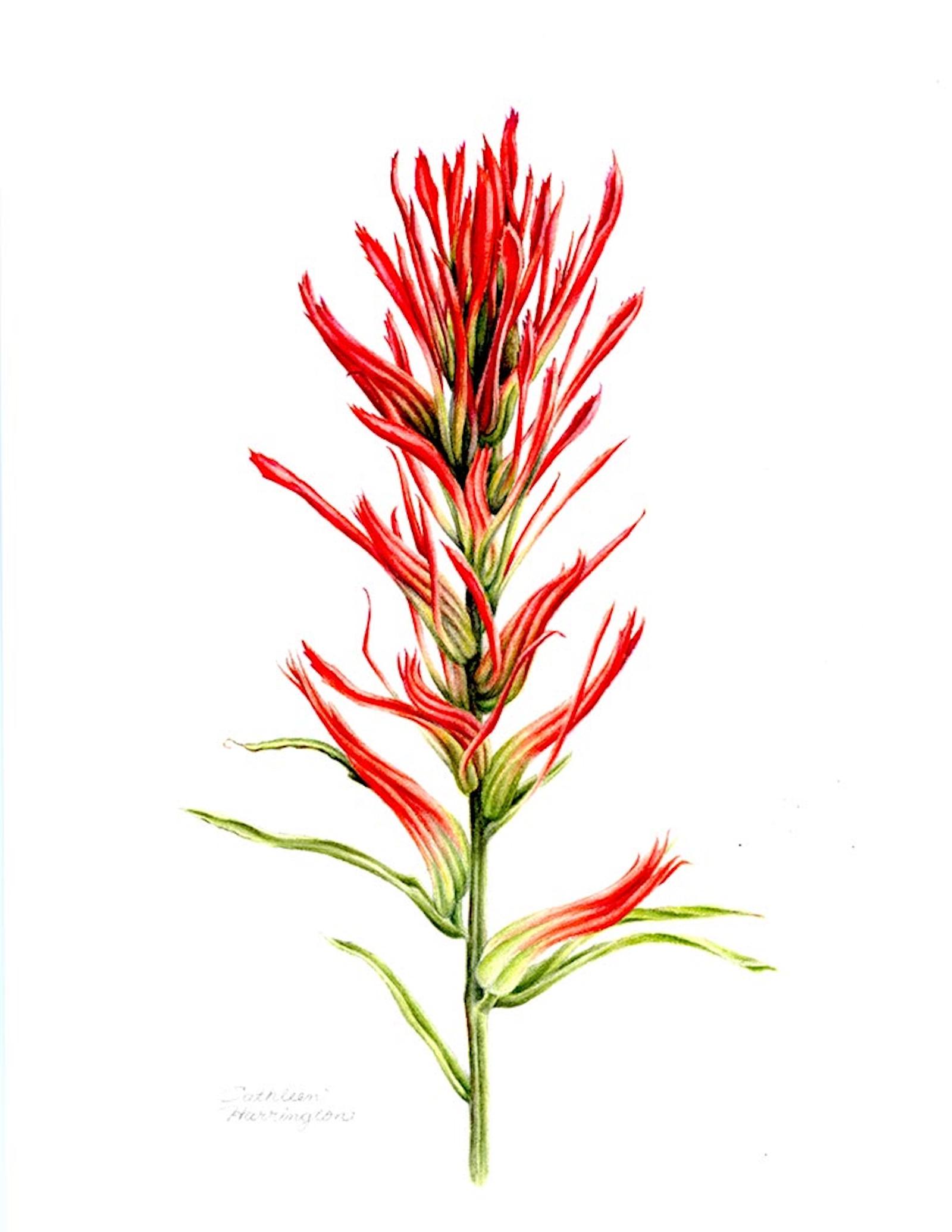

Although botanical illustration manages to merge science and art, for students of the medium, realism reigns.

“I like to keep it pure. There’s another whole branch to the more artistic side,” Overy said. “It’s more about the audience and depends on who I’m drawing for.”

As for botanical prints, the art market includes a wide variety.

“I have several botanical prints, and I really love them,” said Overy, the author of “Sex in Your Garden” and “The Foliage Garden.”

Overy provided an overview of botanical illustrations throughout art history.

“The woodcuts were amazingly good for the 15th century. Engraving on metal with a very sharp stylus altered everything with amazing detail, shading by crosshatching with the stylus. Botanical illustrations were in fashion, and everybody wanted botanical prints during a horticultural mania. Everyone wanted new plants from new countries, and they wanted the marvelous prints they could buy or books with prints in them that gave accurate descriptions of plants. The prints were an exciting innovation and very lucrative.”

Overy firmly opposes taking botanical illustrations from books. “It’s awful to take them out of books. Books should stay intact. That’s a treasure just as it is and practically worthless if you take the illustrations out,” she said.

Overy and collectors value engravings over lithographs.