All of these efforts demonstrate the Swiss-born sculptor’s uncanny knack for updating mid-century tropes—and Bove is a busy borrower, indeed. Her work can put you in mind of David Smith and Anthony Caro’s balancing acts of form, as well as Donald Judd’s obdurate emphasis on thingness. More crucially, Bove’s preferred method of improvisationally crushing, crimping, and bending square steel tubing with an industrial power hammer recalls John Chamberlain’s mangled auto bodies. The tubes, something of a Bove signature and usually powder-coated in satiny finishes, are often draped or wrapped around stubby cylinders in black, conjuring contrasts between soft and hard, malleable and rigid out of heavy metal. Sometimes she adds a soupcon of Richard Serra to her recipe with elements sliced from raw steel plates.

Installation view, Carol Bove: Chimes at Midnight, David Zwirner, New York, April 29 – June 19, 2021.

Written, directed by, and starring Orson Welles, Chimes at Midnight (1965) is considered a high point of the legendary auteur’s filmography after Citizen Kane (1941), when his reign as the “boy wonder” behind the greatest movie of all time was cut short by an artistic temperament ill-suited for Hollywood. Chimes features Welles as Shakespeare's Fallstaff, the rotund, boisterous knight of the Henriad tetralogy who becomes carouser-in-arms with young Prince Hal before the future king disavows his old friend once he ascends England’s throne. In Fallstaff, Welles found the perfect counterpart to his own outsized persona, a larger-than-life character who, much like the filmmaker himself, was both buffoonish and tragic. Welles seemed to accentuate the comparison by filling the screen with Fallstaff’s bulk, transforming him into a titanic presence whose monumentality inspired Carol Bove to title her latest, and grandest ever, installation after the film.

One of three concurrent outings by the artist, and one of two exhibitions at Zwirner venues uptown and down, Chimes is ensconced in the gallery’s W 20th Street space, which has been painted a brooding shade of gray for the occasion. At Zwirner’s E 69th address, meanwhile, the mood is lighter with small, pastille-colored sculptures accenting the location’s elegant, Upper Eastside manse. In addition to Zwirner, Bove also has a quartet of public art projects gracing the Metropolitan Museum’s façade.

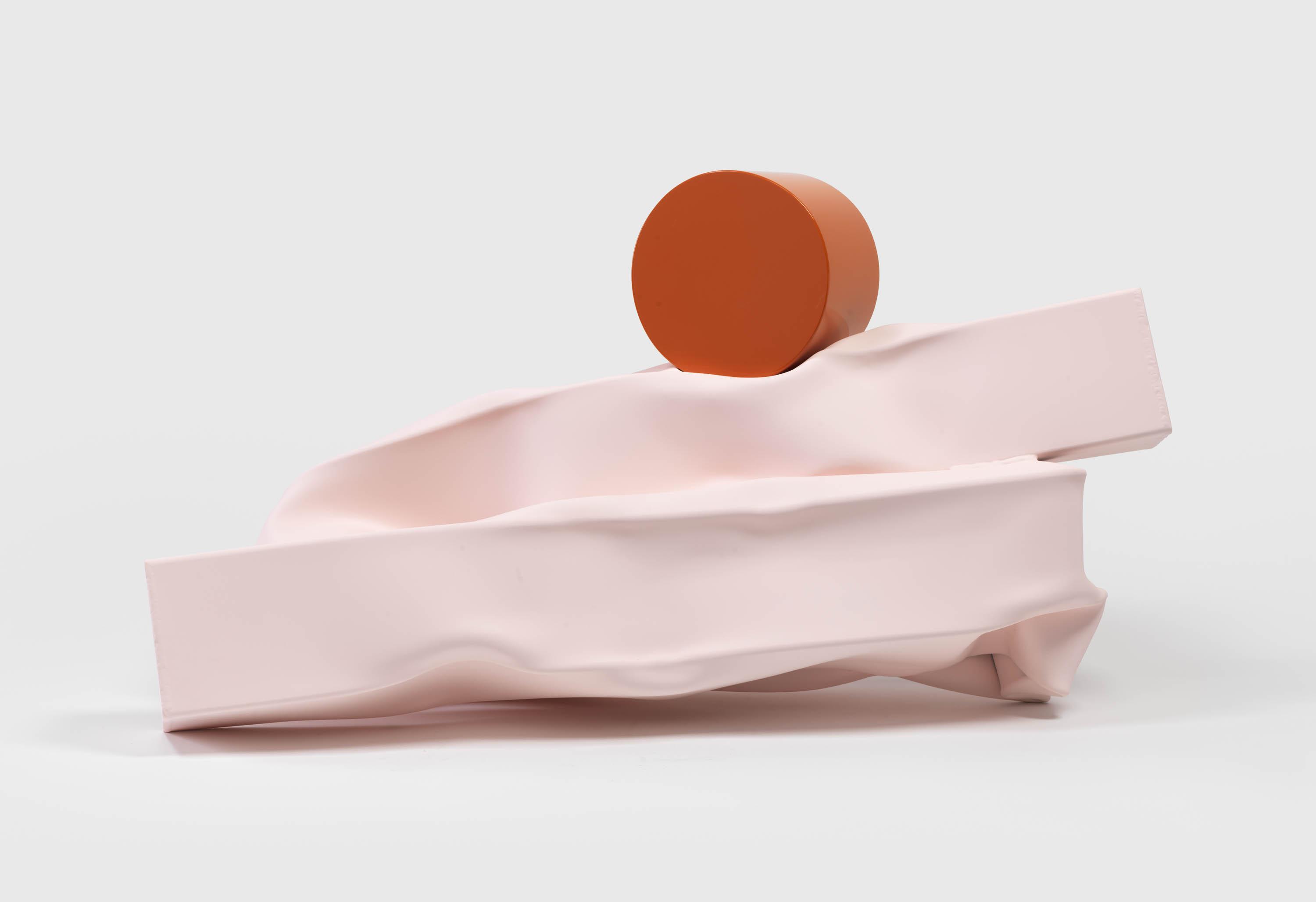

Carol Bove, 2020-008, 2020.

Carol Bove, Chimes at Midnight VI, 2021 (detail).

The last figures prominently in Chimes with a half-dozen or so vertically oriented sculptures featuring narrow, upright shards of the stuff whose edges have been left rough and beaded by the cutting torch. Resembling totems, they’re propped against each other, serving as backdrops for Bove’s more familiar motifs, which, dipped here in primer orange, snuggle against their brutish partners like debutants dancing with stevedores. Toughness and tenderness co-exist anxiously in each pairing, and just as Welles’s Falstaff loomed over movie audiences, these objects tower ten feet and more above the viewer.

Installation view, Carol Bove, David Zwirner, New York, April 29 – June 19, 2021.

Uptown, the offerings, wall-hung or set on tables, are more modestly scaled. In the front gallery, a group of them twist around like ribbons, echoing the interior’s beaux-arts molding in a palette of yellows, greens, olives, and pinks. In back, two sculptures, one white, the other a pale mauve, create a ghostly contrast with silk wall coverings printed in a rusty fishnet pattern. All of these objects share a sinuousness that reminds you of brushstrokes—a propensity to evoke painting in three dimensions which Bove shares with some of her aforementioned predecessors.

Installation view, Carol Bove, David Zwirner, New York, April 29 – June 19, 2021.

Further north, Bove’s work occupies the niches flanking the Met’s main entrance. It’s only the second entry in a commissioning series launched by the museum to complement its wildly popular rooftop garden installations, though Bove’s foray into architectural ornamentation has the virtue of being free to visitors.

Adorning buildings with figures is as old as civilization itself, reflecting the stubborn persistence of the human figure in architecture and art. While nominally abstract, Bove’s pieces are firmly within that tradition as they distill classical antiquity and its numerous revivals. Here, Bove does her snake charming routine with writhing tubular elements sandblasted to a silvery sheen. These interact with mirrored disks reflecting the tony apartment blocks across the street. Set on their vertical axes, the platters range from edge-on to profile view as the sculptures contort to suggest standing or sitting. The former wander over the latter to evoke heads and, in one instance, someone in a wheelchair.

Bove calls her piece The séances aren’t helping, but why? Perhaps it’s a metaphor for a contemporary culture stuck in the past, unable to reach beyond itself. That wasn’t a problem in Welles’s time, but given that today’s art has become a blur of shallow homages and indiscriminate appropriations, Bove, who knows how to adroitly calibrate references to make them look new, may have a point.