The DAM’s $175 million upgrade commemorated, in Mile High City style, the fiftieth anniversary of the Ponti building, one of the early landmarks in the downtown Denver Cultural Complex. Formerly known as the Ponti Building or the North Building, the structure now is known as the Martin Building in homage to Denver Art Museum Board Chairman Lanny Martin and his wife, Sharon Martin, contributors of the lead gift of $25 million.

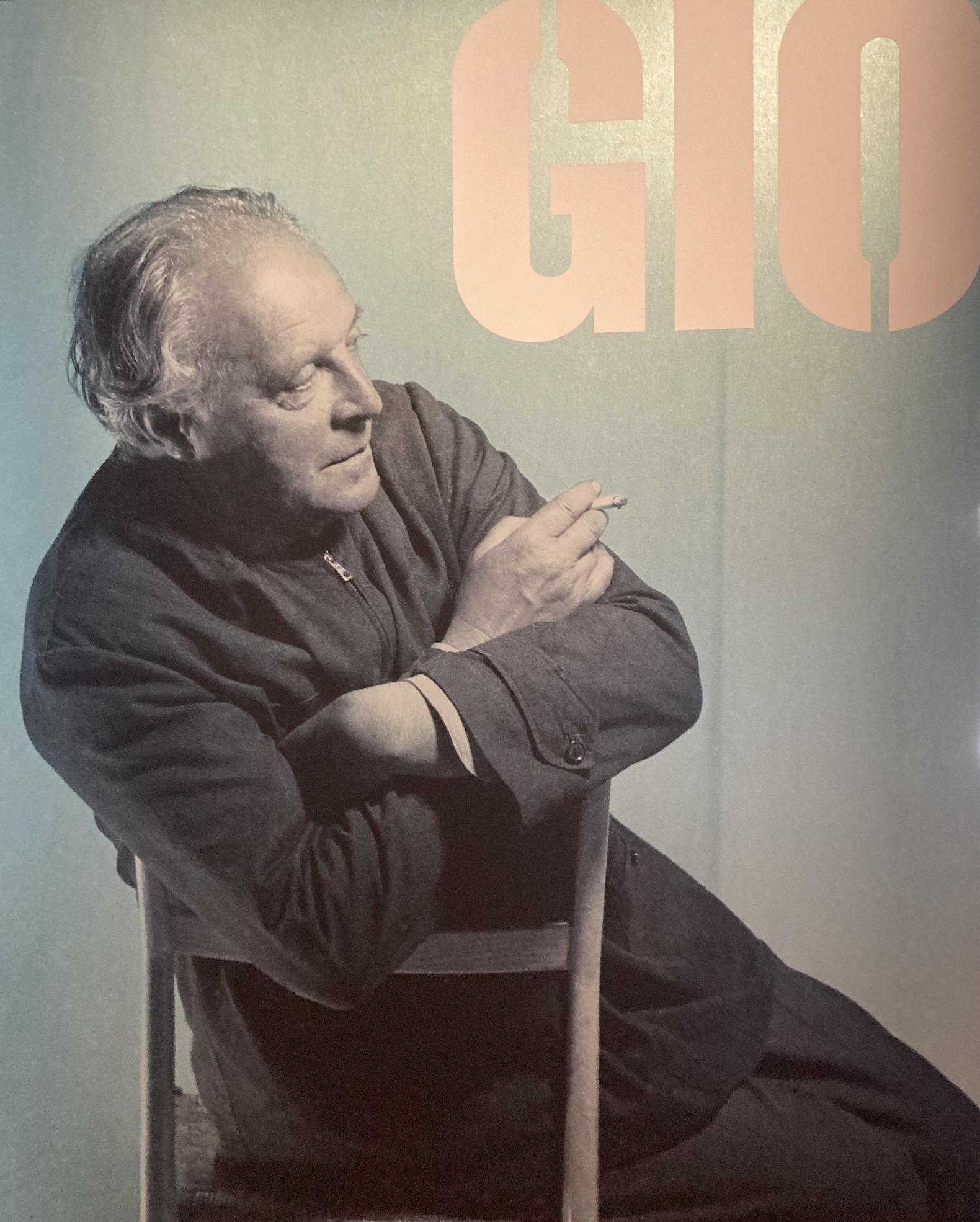

The DAM’s innovative structure is the only building Ponti, the celebrated Italian modernist, completed in North America. Ponti was seventy-four when hired to collaborate with Denver-based James Sudler Associates on the site-specific structure.

“Ponti worked with a weird piece of real estate, triangular,” Heinrich adds. “He designed the first high-rise art museum with nine floors—seven above ground and two underground—not a big Beaux-Arts temple. It was really a gamechanger on its own.”