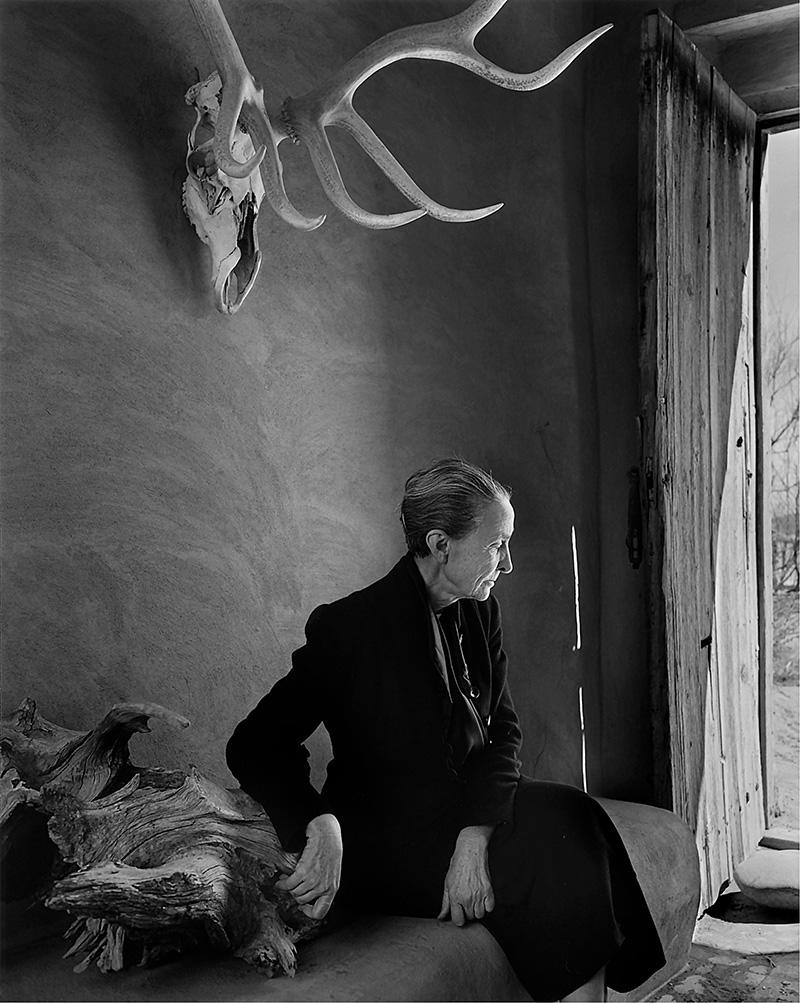

“It started in 2015," Feldman explained in a conversation with Art & Object. "I was invited to a conference in New Mexico and for the first time I visited Georgia O’Keeffe’s studios in Abiquiú and Ghost Ranch. When I saw all those found objects she collected, not just a few, but thousands of bones, shells, sun bleached wood and stones, I thought ‘Henry Moore would have loved this, especially that skull.' That was the spark.”

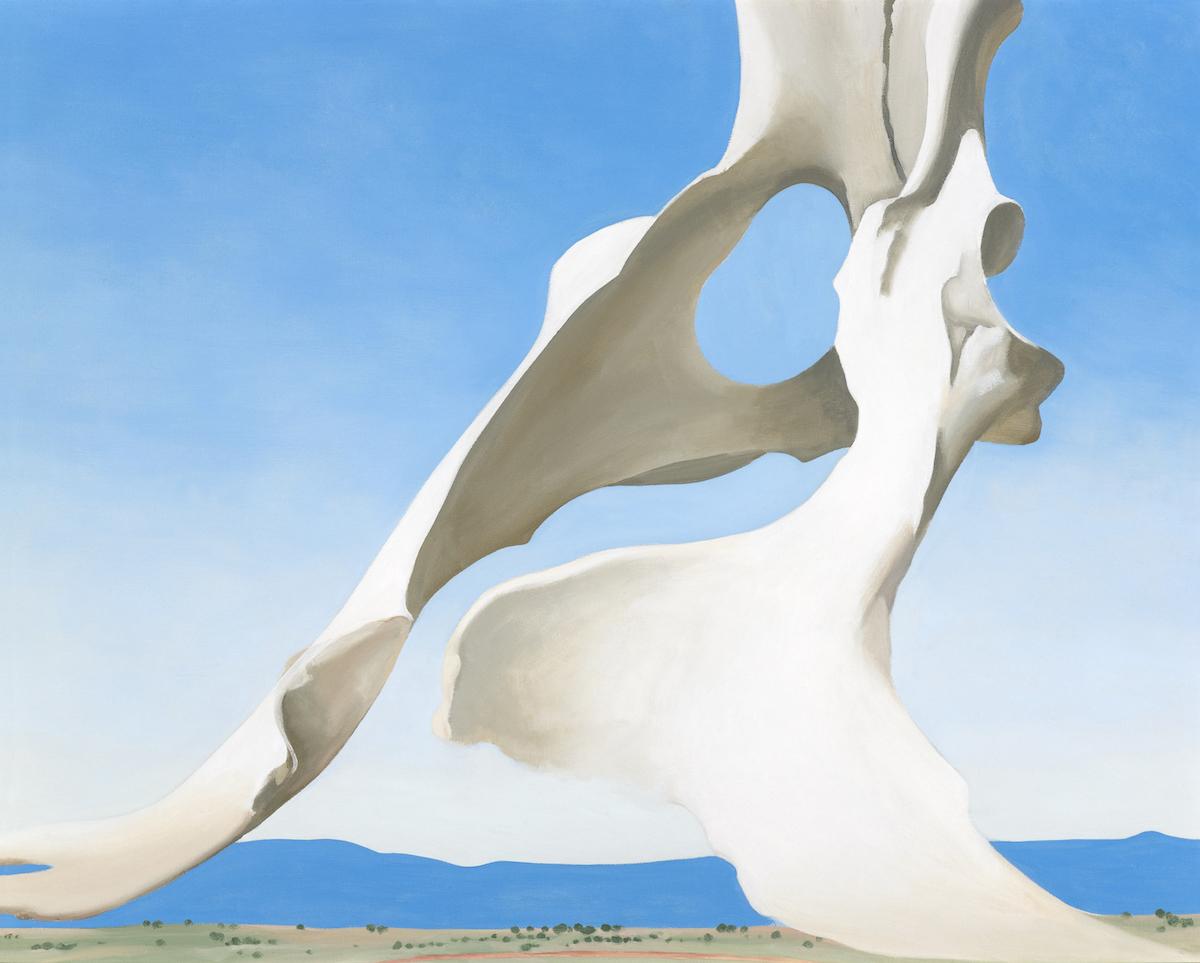

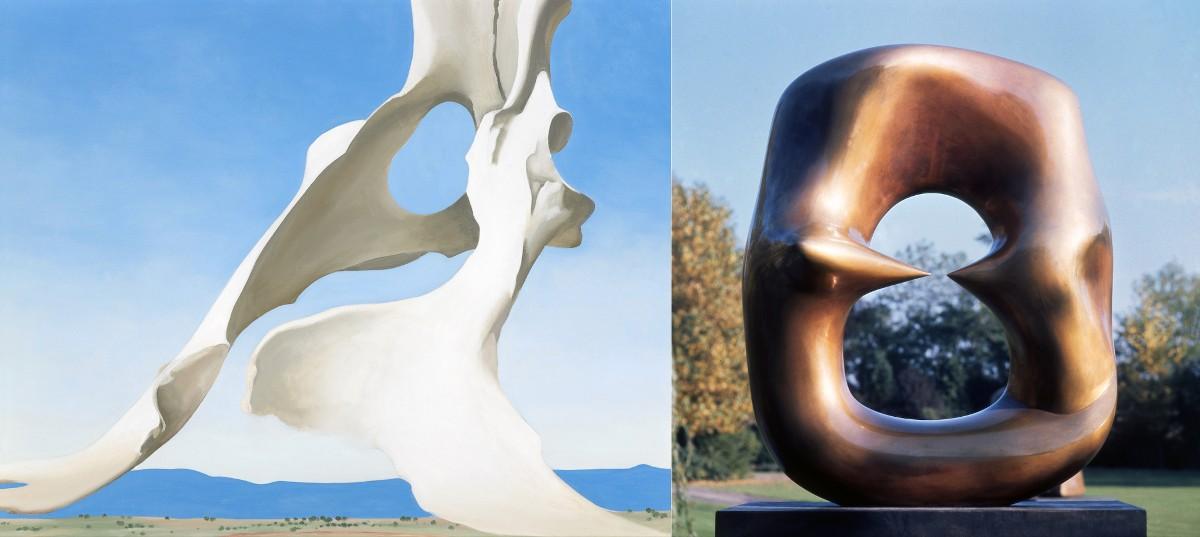

Left: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), Pelvis with the Distance, 1943. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, gift of Anne Marmon Greenleaf in memory of Caroline Marmon Fesler. Right: Henry Moore (1898-1986), Working Model for Oval with Points, 1968-1969. The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadam, England, gift of the artist, 1977.

American artist Georgia O'Keeffe's (1887-1986) iconic flower paintings embody the essence of feminine identity while British sculptor Henry Moore's (1898-1986) abstract sculptural forms surge boldly into space with a powerful masculinity. Paired together for the first time in "O'Keeffe and Moore: Giants of Modern Art" at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, this exhibition delves deeply into their mutual sources of inspiration in the natural world, illuminating both artists in new ways and challenging what we thought we knew about their lives and work.

The concept for the exhibition was initiated by Anita Feldman, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs at the San Diego Museum Art. As a Henry Moore scholar, author, and prior member of the Moore Authentication Committee at the Henry Moore Foundation for 18 years, Feldman was uniquely positioned to investigate new ways of thinking about Moore’s contributions to Modernism.

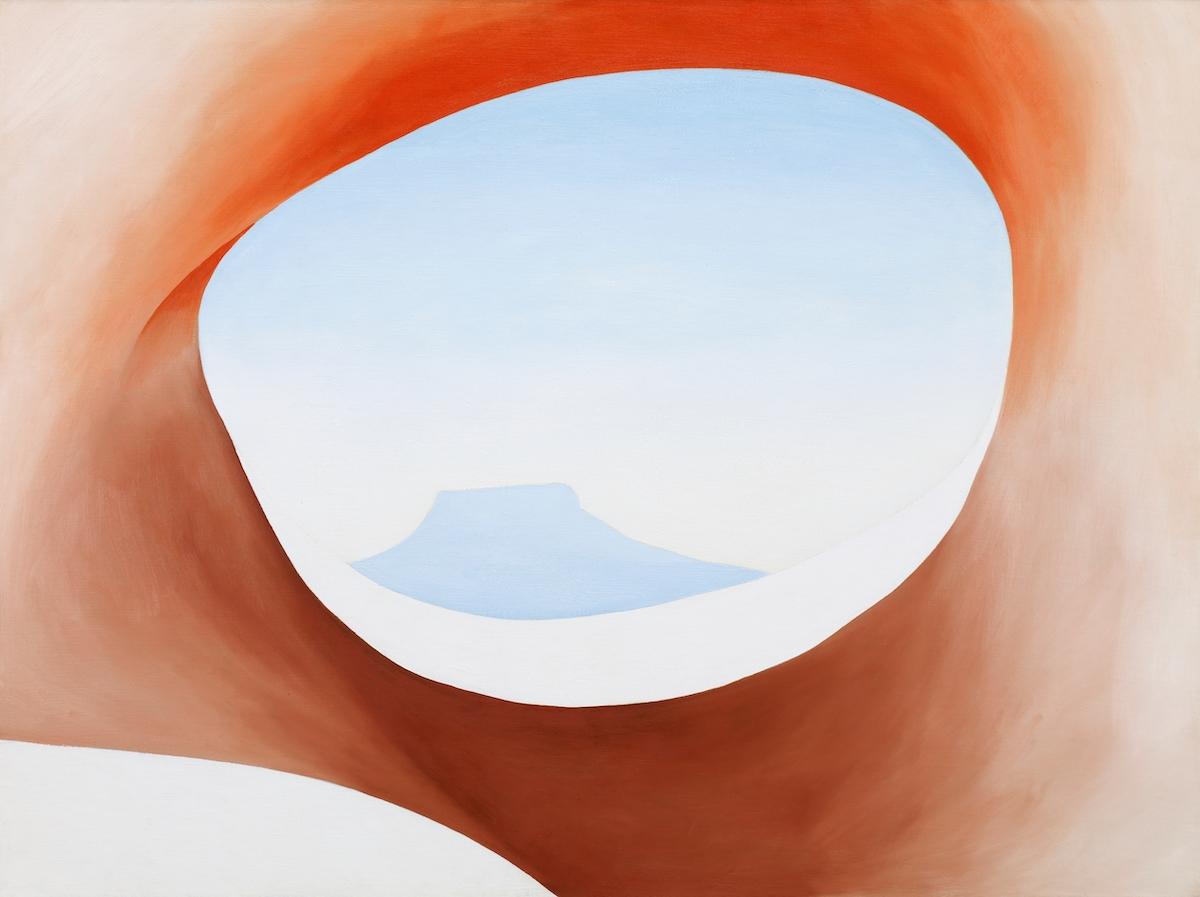

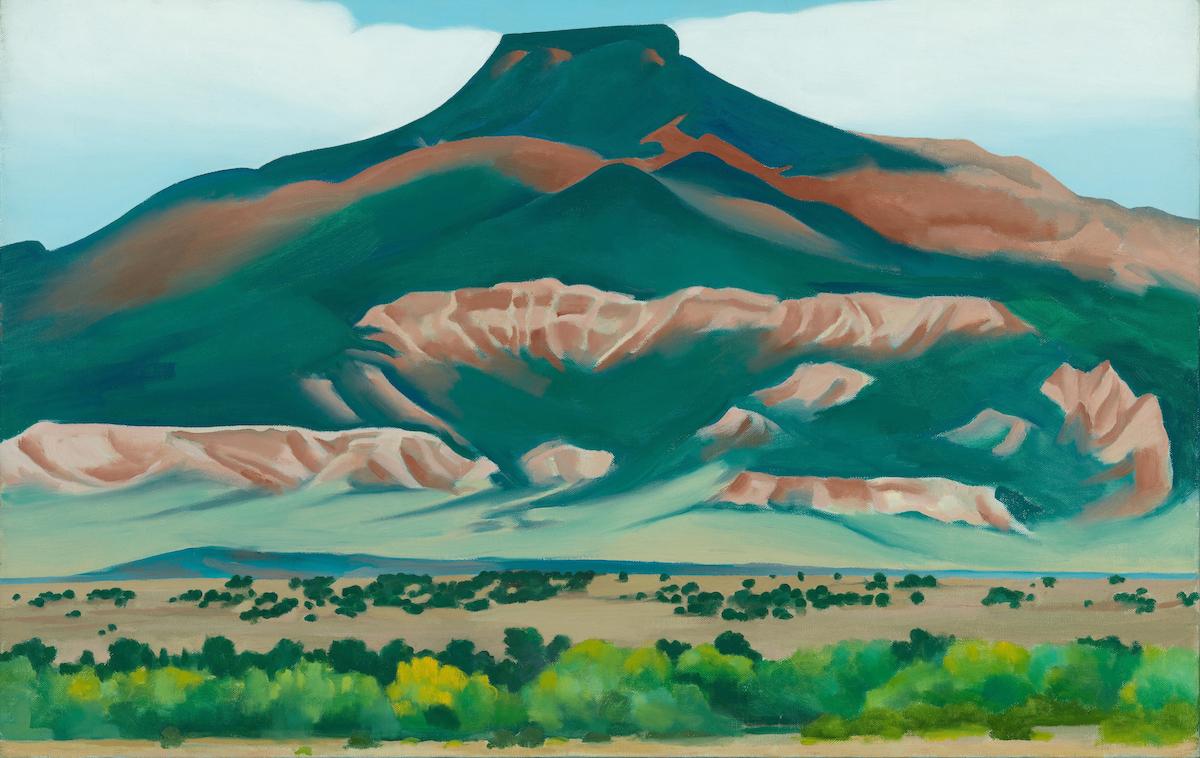

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), Le mont Pedernal, 1941. Santa Fe (Nouveau-Mexique), Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation.

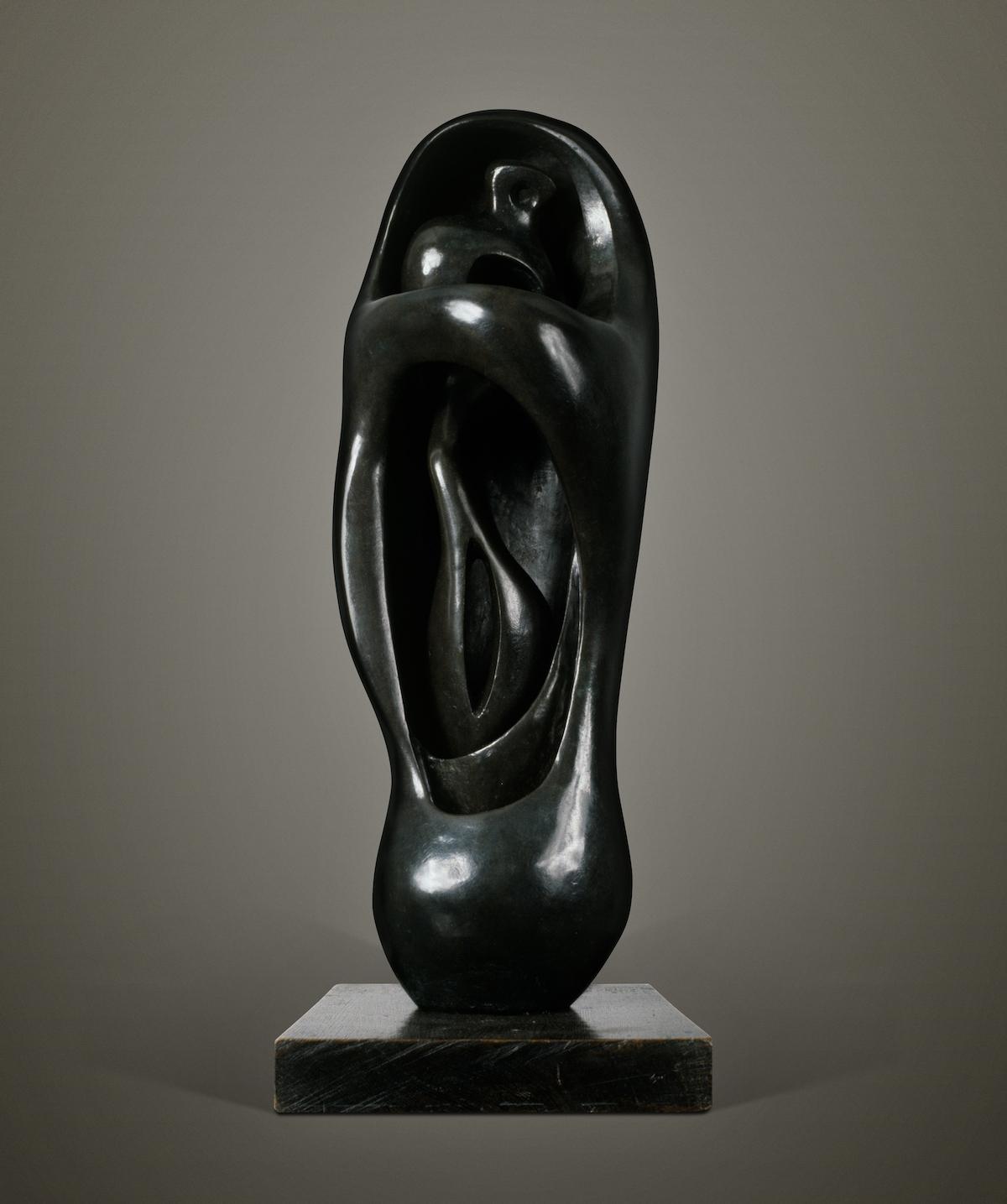

Henry Moore (1898-1986), Working Model for Upright Internal/External Form, 1951. The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham, England, gift of Irina Moore, 1977.

Feldman’s encounter and the revelations she found by comparing both artists' source materials became the foundation for this illuminating exhibition. Meticulous recreations of Moore's and O’Keeffe’s studios are a central focus and include the original contents from O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch studio in the hills of New Mexico and Moore’s Bourne Maquette Studio in Perry Green, a small hamlet surrounded by sheep fields in Hertfordshire, England. Moore referred to his collection as his “library of natural forms”— the objects include locally scavenged cow and sheep bones as well as the skull of a rhinoceros, a giraffe neck bone, and minke whale vertebra, rare finds given to him by his friend, zoologist Julian Huxley.

“Discovering O’Keeffe’s and Moore’s mutual surrealist influences was interesting as was their surprising juxtaposition of scale in paintings and sculpture," Feldman continued. "Once we decided to include their studios in the exhibition, with their actual collections of found objects, the logistics became complicated. Transporting bones over international borders was challenging. The show was originally planned for 2021, but then came COVID.”

The parallels in the life and working methods of two artists who would never have been mentioned in the same sentence are striking. They both came from large families. O’Keeffe was one of seven children and Moore was the seventh of eight children. They both abandoned their formal training, and both retreated to rural landscapes to do their finest work. Drawing also remained a touchstone throughout their careers. They were successful and admired in their own lifetime. They both died in the same year.

But as Co-curator Iris Amizlev, Head of Community Engagement and Projects at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, observed, “Given the many similarities in O’Keeffe’s and Moore’s artistic interests, habits, formal explorations and iconographic vocabularies, it’s difficult to fathom that no extensive exchange of ideas ever occurred between them.” As a matter of fact, they may have only met once, at Moore’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946. O’Keeffe was the first female artist honored with a solo exhibition at MoMA earlier that same year.

Henry Moore (1898-1986), Reclining Figure, 1959-1964,. The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham, England, gift of Irina Moore.

Peering at the sky and the landscape through an irregular circular void in a bone was a vehicle by which both Moore and O’Keeffe discovered a pathway to abstraction. That singular image of a brilliant blue sky framed by the curve of a bone echoing the human form became the key motif for the stunning installation of over 120 works in the Montreal exhibition and it was featured on the cover of the beautifully illustrated catalogue.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), White Iris, 1930. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Gottwald.

The show spans the entire career of both artists and is accompanied by photographs of the artists as they aged. O’Keeffe’s subtle nuances of color in early abstractions like Blue Line from 1919 and later within the largely white surface of The White Trumpet Flower, 1932 are lost in reproduction. Seeing the surface of these works up close was like seeing them for the first time. White again predominates in her white-lacquered bronze sculptures whose elegant, flowing curves make them feel alive, in sharp contrast to the weighty, monumentality of Moore’s reclining figures which seem born of the earth.

The Magritte-like surrealist elements particularly in O’Keeffe’s landscapes from the 1930s-1940s and in Moore’s small, bronze Stringed Object, 1938 and Helmet, 1939 share a magical view of the world communicated through juxtapositions of scale, metamorphosis, and the interiority of forms. Despite the ambitious scope of "O'Keeffe and Moore," the viewing experience is intimate, personal, and sensuous. We leave the exhibition feeling we have actually met these "Giants of Modern Art." The exhibition moves on to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from October 13, 2024 – January 20, 2025.