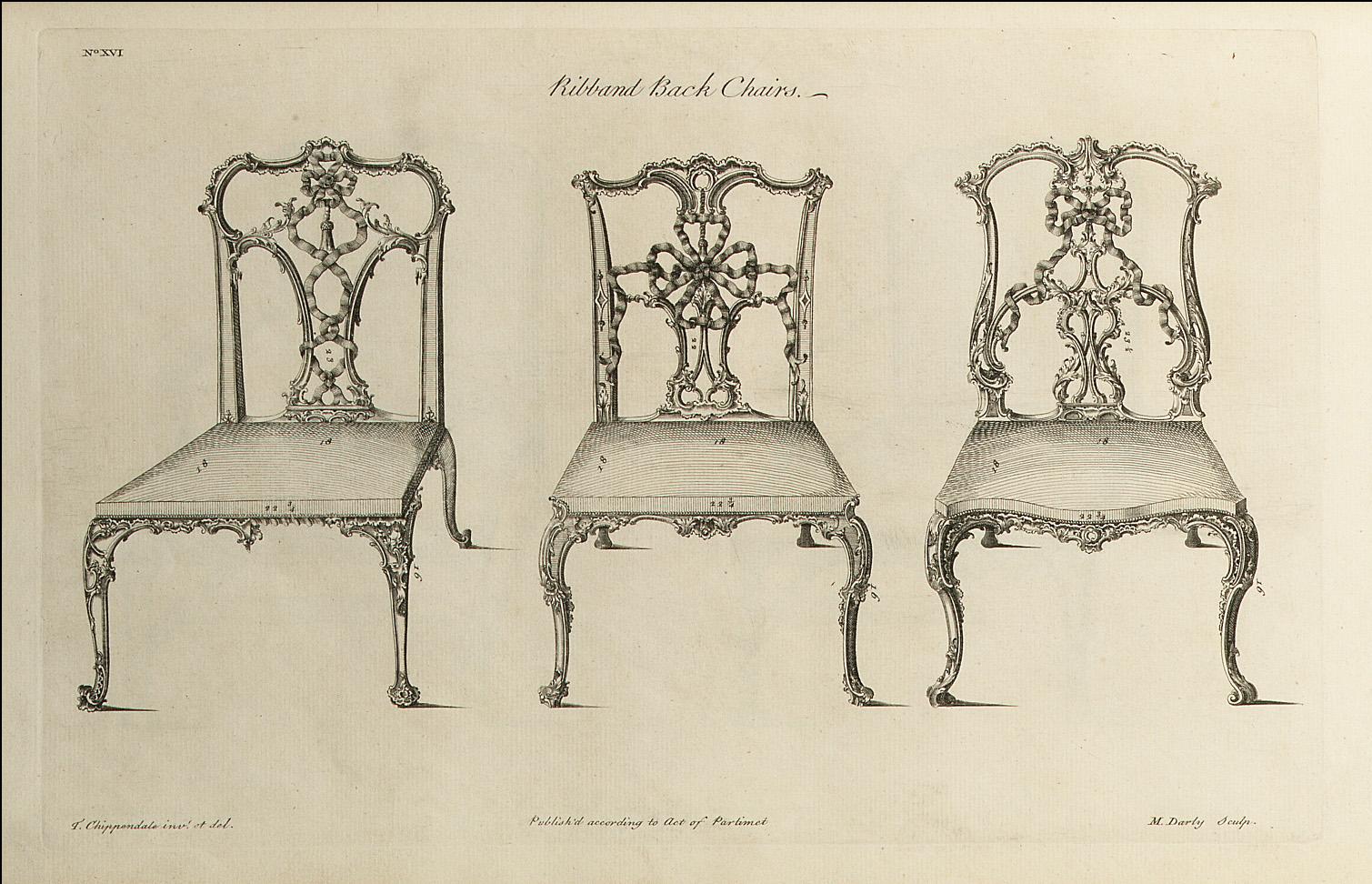

The show's title is adapted from the architect Owen Jones’ 1856 publication The Grammar of Ornament. The book preserved an approach to ornamentation that was used by European architects in the second half of the nineteenth century.

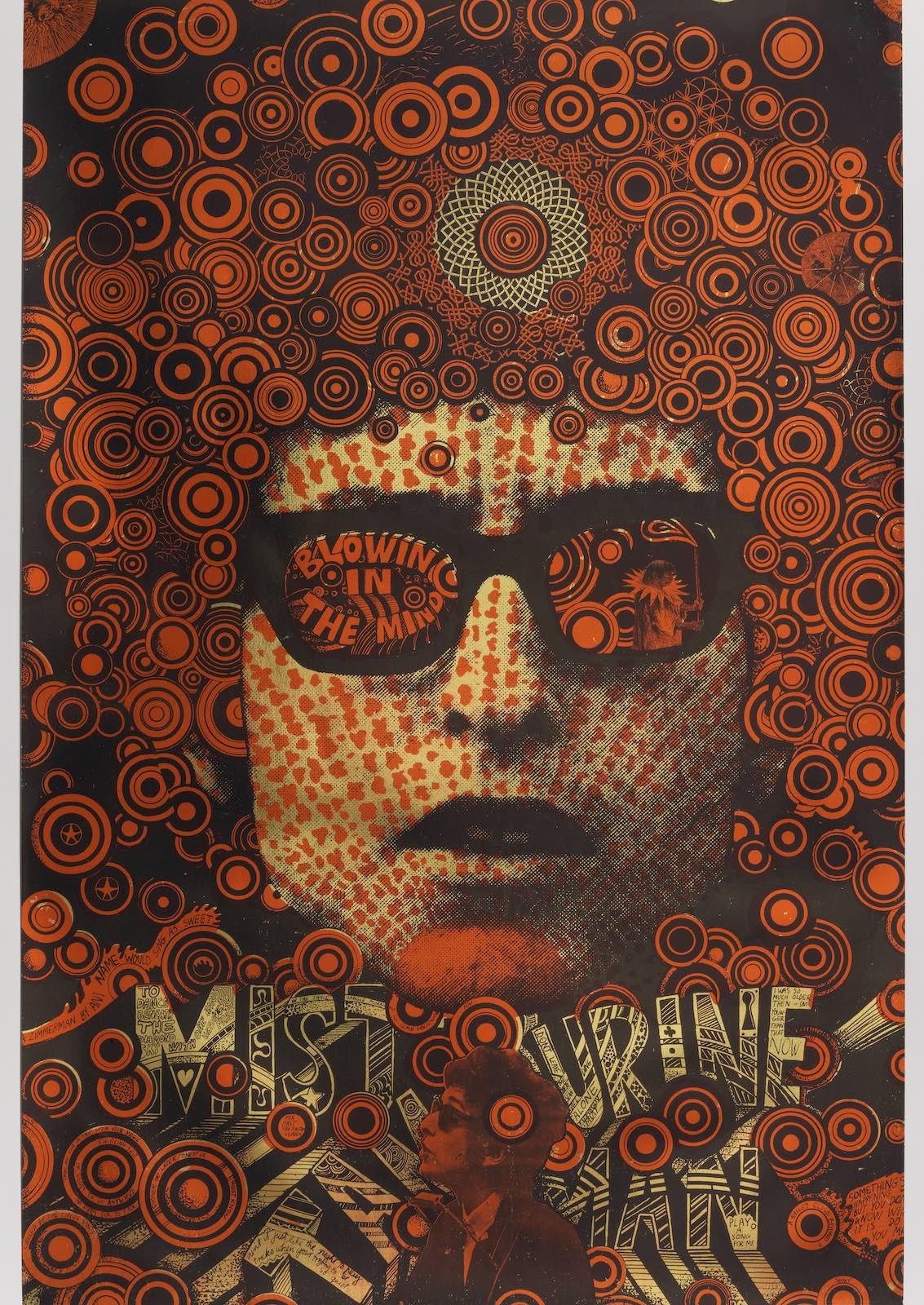

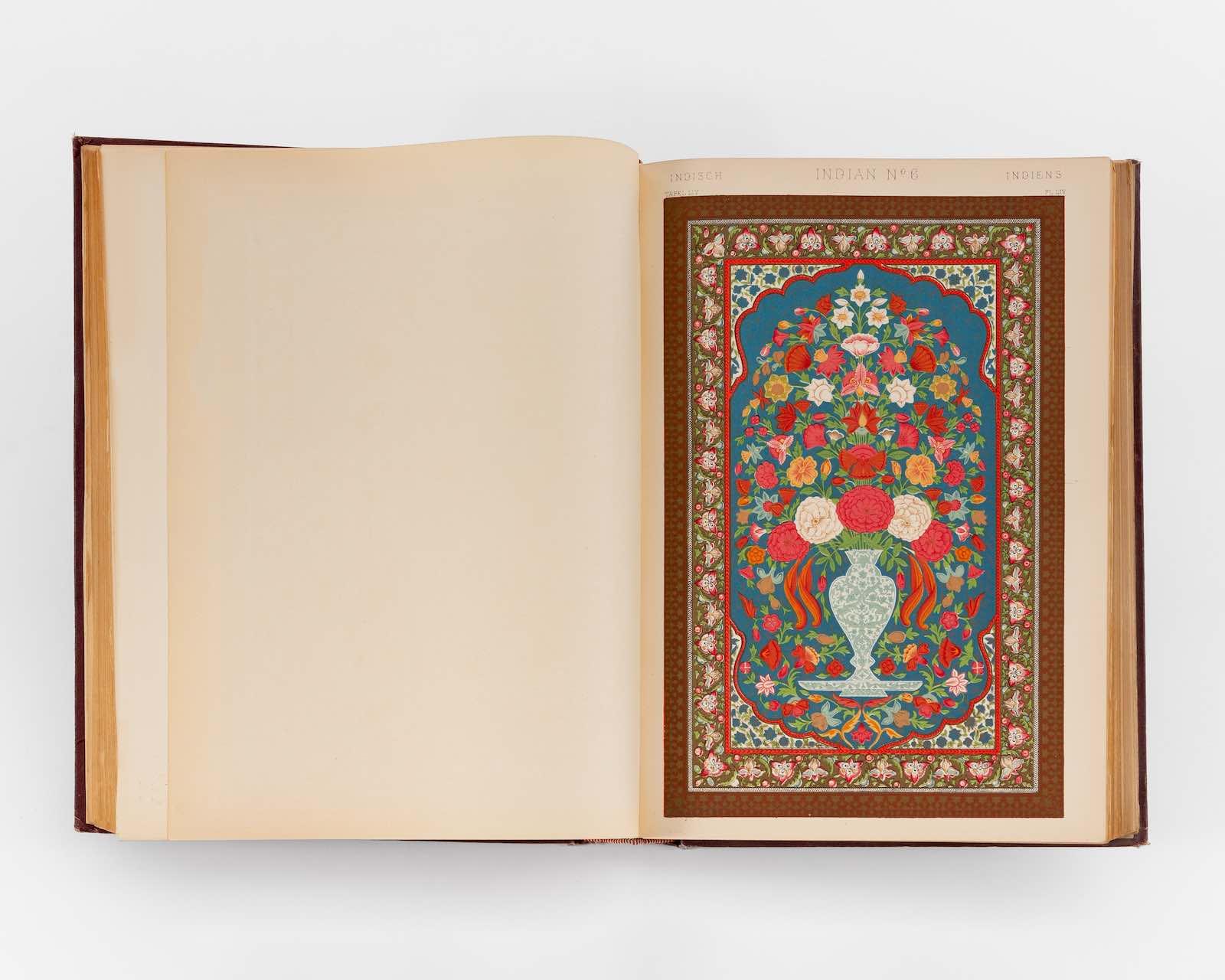

Here we have Jones’ beautiful watercolors on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum representing examples of ornamentation from ancient times through the nineteenth century in spectacular color plates. Jones’ renderings illustrated the intoxicating beauty of ornament.

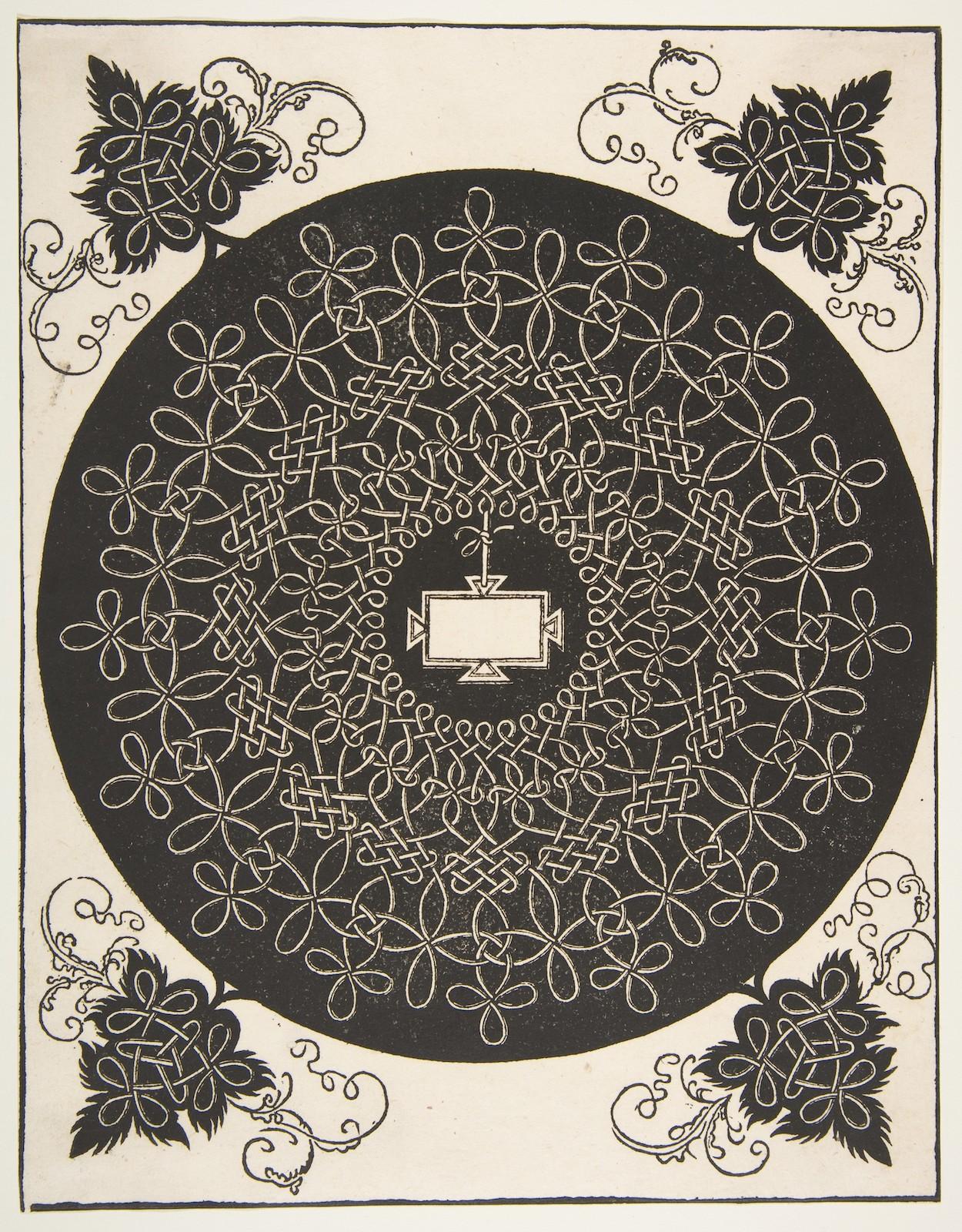

Initially, Jones considered some cultures more aesthetically accomplished than others. He ranked Islamic design at the apex, disparaging those from China in favor of the elaborate geometry found in examples from nature. Ultimately, Jones withdrew this argument about the inferiority of Chinese design. In 1867, he devoted an appendix volume to Chinese ornament. The drawings shown here were copied from artifacts in South Kensington Museum’s collection, and Jones’ joy in Chinese detail and embellishment is evident.