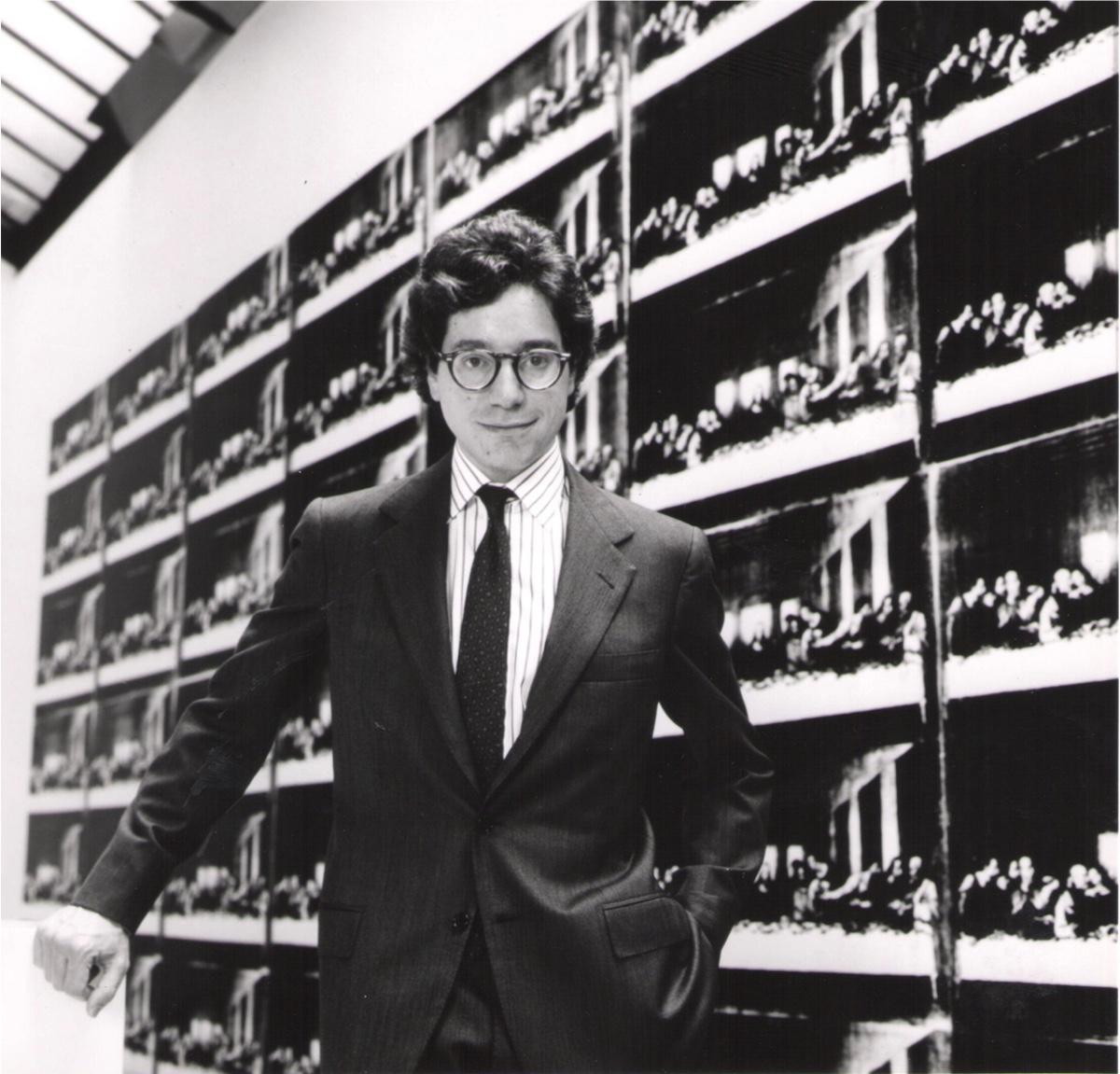

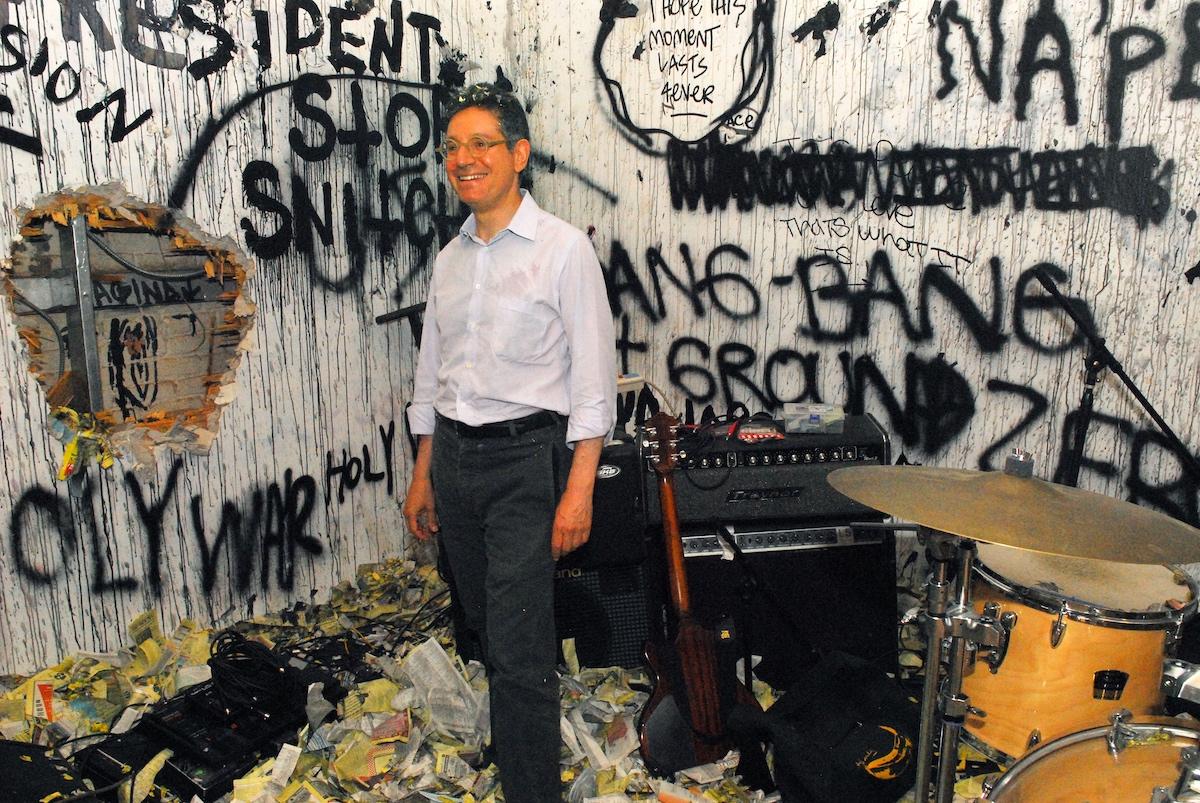

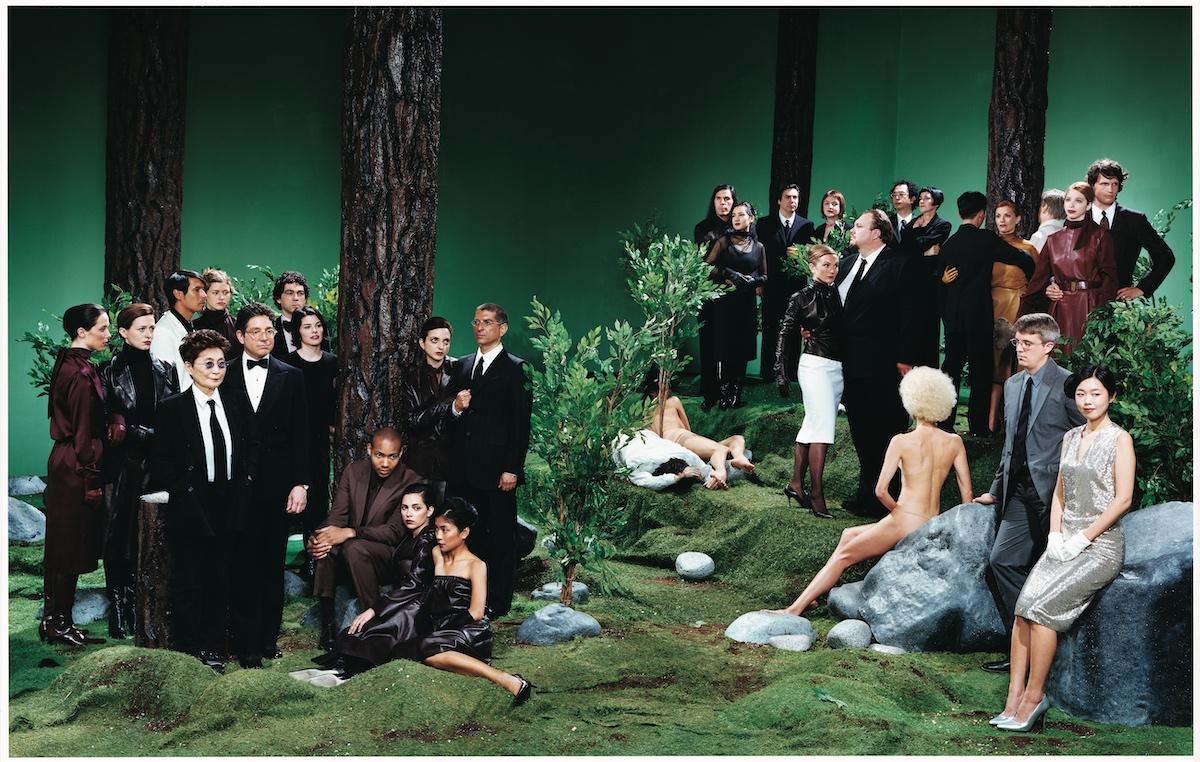

In many ways, it’s a theme that’s emblematic of Deitch himself, and could be one of the keys to his success. It puts artists first, freeing them to wander where they will, rather than corralling them into a mindset. It was in this vein, in 1996 when he opened Deitch Projects in New York. If artists needed it, he offered up to $25,000 as a production budget and provided studio space, assistants, and materials. If the project sold, the money was reimbursed and the gallery and the artist evenly split the rest. If it didn’t, Deitch would add the project to his collection.

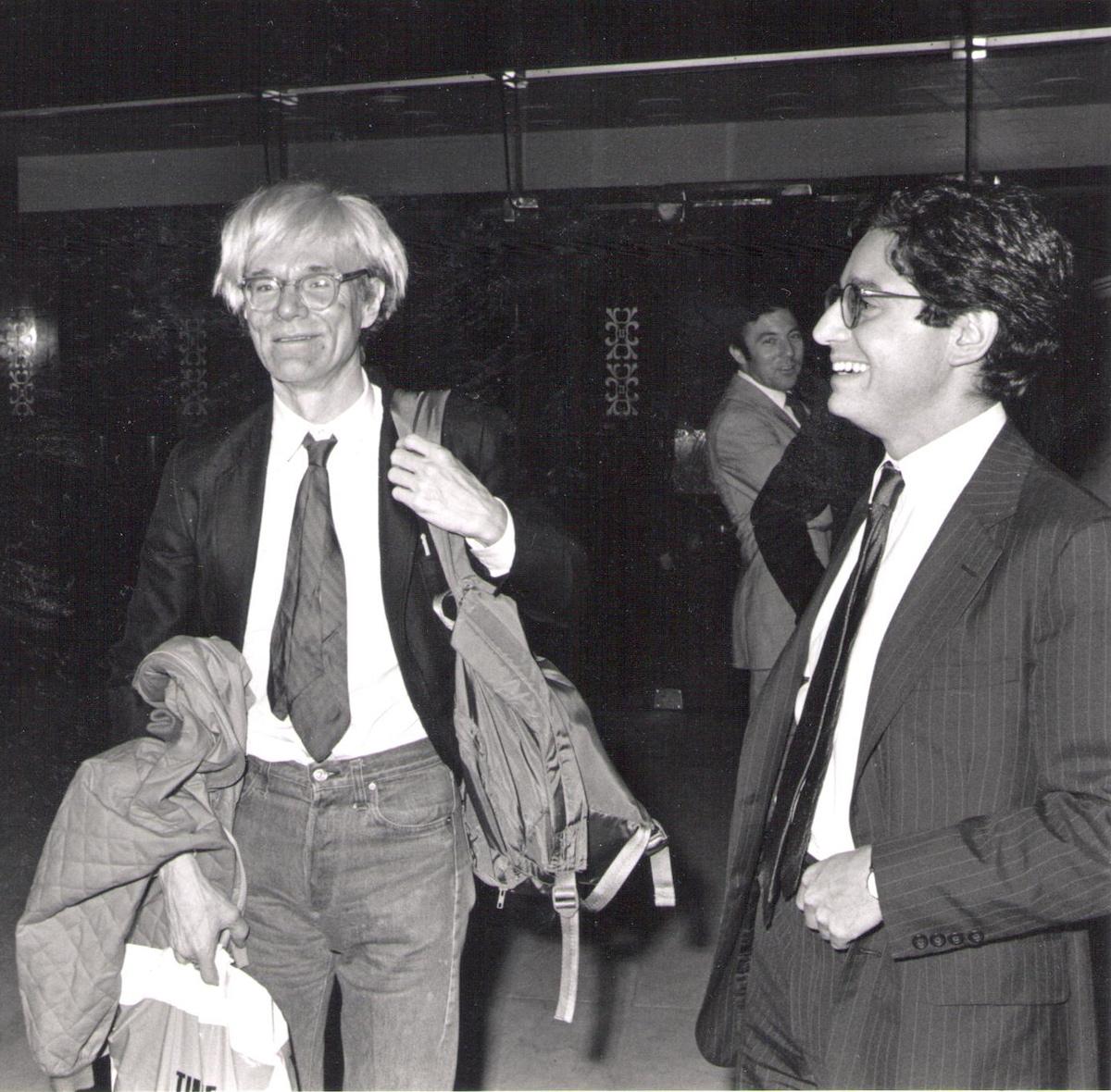

It’s an ethos that took root early when he was just a bright-eyed kid from Connecticut who showed up one day on the doorstep of the John Weber gallery in the mid-1970s. Newly matriculated from Wesleyan University where he studied art after changing his major from economics, Deitch was eager to find a way into the art world.

Inquiring about a job, he learned that the secretary just quit and there was an opening. But Weber would have to approve any hire and he was away at Art Basel for at least another week and was almost certain to hire a pretty young woman anyway. So Deitch, instead of waving goodbye and knocking on the next door, proposed working a week for free. If it didn’t work out, they would part ways.

“They inherited the gallery of Virginia Dwan,” Deitch says, referring to the legendary gallerist who died last summer. “At that time it was the leading gallery for minimalism, conceptualism, language art, and Earth art, and I met all those people!” Artists like Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg used to come by, and each day Carl Andre would come around three o’clock to pick up his mail. Younger artists who wanted to meet him would gather at the gallery and Deitch would play host.

“It was an amazing education,” Deitch recalls. “There is a discourse at the leading edge of the art community at all times. At that time it was minimalist, conceptualist. I look at art history, Manet would join an artistic circle every afternoon.”