As it happens, this exhibition arrives amid a wave of renewed interest in Ringgold after years of fitful recognition. For instance, when the Museum of Modern Art reopened in 2019 following the completion of a major expansion, it installed Ringgold’s canvas Die (1967) alongside Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) as a “response”—a gesture which raised Ringgold’s profile even as it seemed like an attempt to divert attention from Picasso’s reputation as a sexual predator. More recently, she appeared in the news when a long-neglected mural commissioned by the city in 1972 for the women’s facility at Rikers Island was relocated to the Brooklyn Museum at the artist’s request.

Faith Ringgold: American People, 2022. Exhibition view featuring The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1975–89).

Who gets to be called a “real” American? Throughout the nation’s existence, the answer for white people has been, “we do,” an assertion of privilege that grows ever-more vehement and hysterical during periods of racial panic. We’re now living through such a moment, possibly the most dangerous since the Civil War, thanks to fears of demographic change exacerbated for corporate profit by social media and right-wing cable news.

Given the circumstances, “American People,” the New Museum’s retrospective of African American artist Faith Ringgold seems especially timely. The show surveys Ringgold’s sixty-year career, spanning her roles as a painter, mixed-media sculptor, performance artist, author, activist, and educator. More importantly, the exhibition reveals how Ringgold’s work sees race not only as a matter of identity politics, but also as foundational to U.S. history, and how Black lives mattered to its creation.

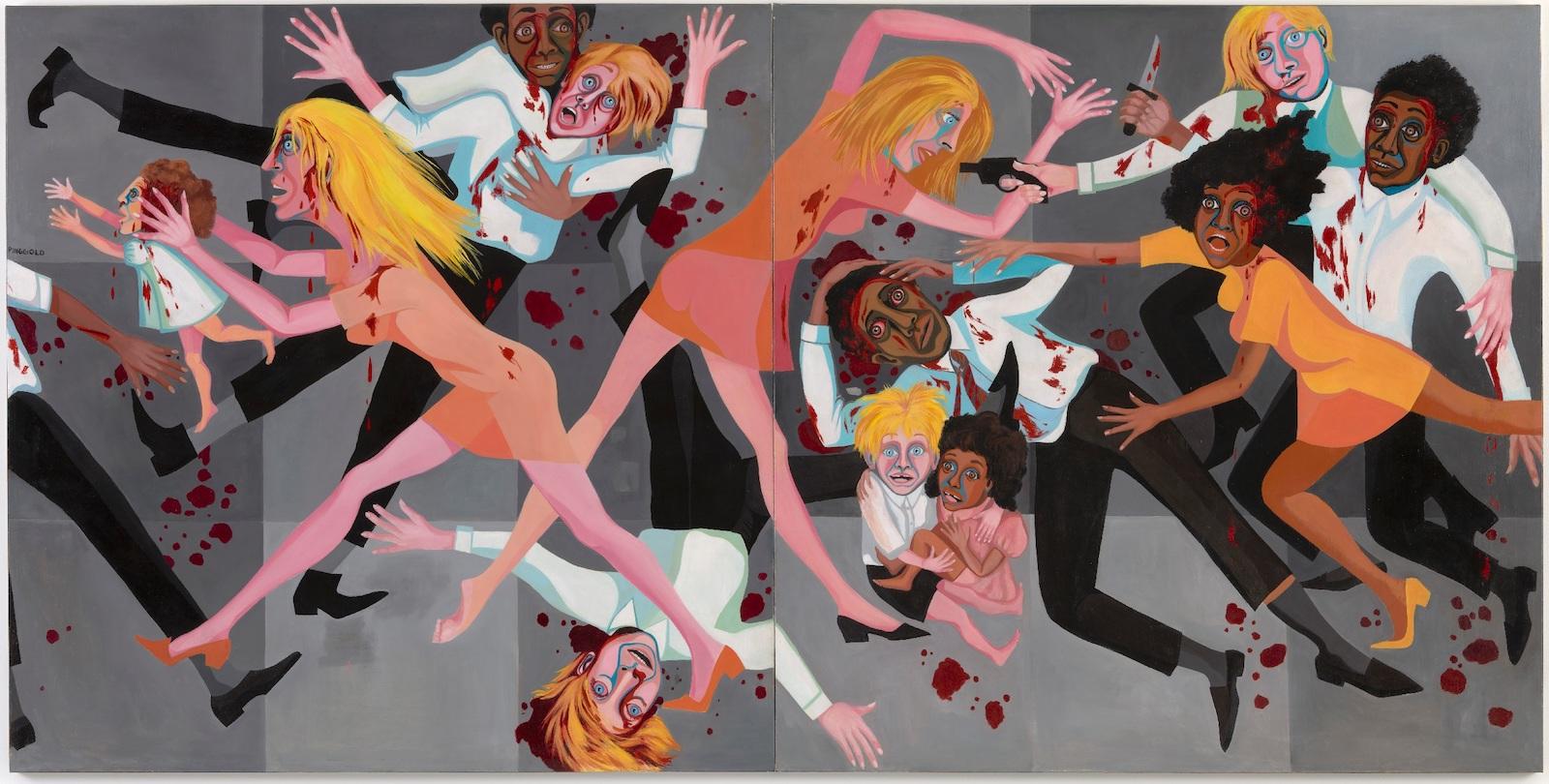

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die, 1967. Oil on canvas. Two panels 72 × 144 in (182.9 × 365.8 cm).

Faith Ringgold: American People, 2022. Exhibition view.

Born in 1930 Harlem, Ringgold’s life has coincided with the struggle for Civil Rights, the Black Power movement, and the rise of Feminism. She committed herself to battling racism and sexism, especially in an art world that blithely overlooked women and people of color—helping, for instance, to organize protests demanding more multicultural inclusivity in museum collections and exhibitions.

In essence, Ringgold was a pioneer of intersectionality, though not in any abstract or theoretical sense. Instead, she borrowed craft traditions from Africa and Tibet to fashion a kind of narrative art that was accessible and grounded in feeling even as it unpacked inconvenient truths.

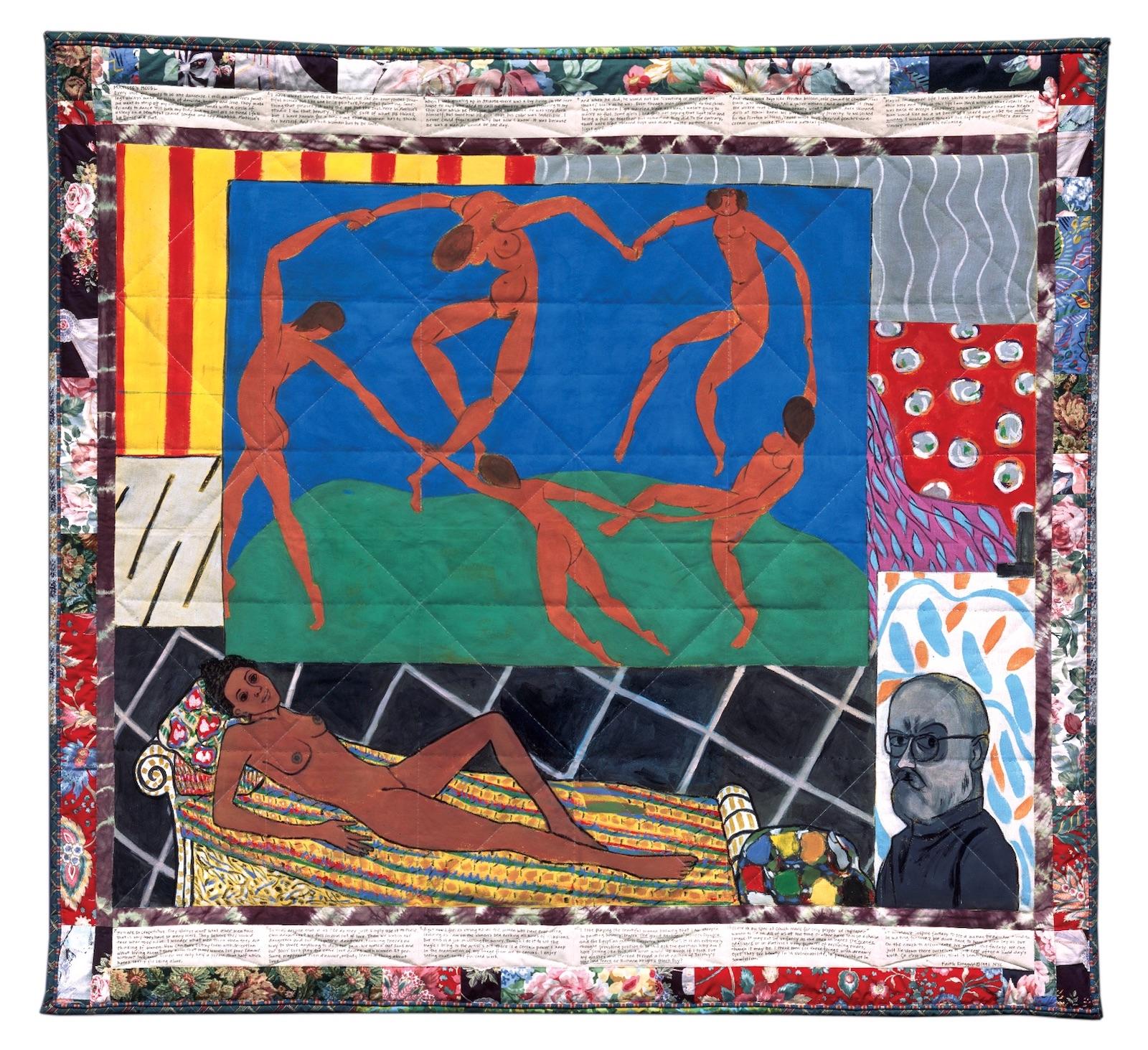

Faith Ringgold, Matisse’s Model: The French Collection Part I, #5, 1991. Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed pieced fabric, ink. 73 1⁄4 × 79 3⁄4 in (186.1 × 202.6 cm).

Her most famous efforts in this regard are her storytelling quilts—actually, paintings on quilted fabric—that relayed both real and fictionalized aspects of her life and memories, along with allusions to Black and women’s history. The quilts cover a wide range of subjects both political and personal from the depredation of Black neighborhoods to women’s body issues.

Ringgold learned quilting from her mother, who in turn learned it from her mother, a former slave, forging a lineage of Matriarchal wisdom that echoes through the quilts. Indeed, their homespun quality makes it easy to mistake them for the efforts of an outsider artist.

However folksy in appearance, Ringgold’s works are rich with art-historical references. In fact, MoMA’s pairing of Die with Les Demoiselles doesn’t seem so spurious when you learn that Ringgold cites Picasso as a major influence—especially on Die itself, which was modeled on Picasso’s Guernica (1937). Ringgold’s admiration for Picasso, as well Matisse, was such that encomiums to both appear in her ebullient story quilt cycle, The French Collection Part I.

With all due respect to Ringgold’s quilts, the previously mentioned Die is undoubtedly her masterpiece. Part of a provocative group of canvases that shares its title with the exhibition, Die measures an impressive six by twelve feet and features a jagged, blood-splattered composition of a black and white citizenry (men in black pants, white shirts, and ties; women in yellow-orange dresses) murdering each other with guns and knives as their mutually assured destruction plays out against a grid of grey blocks. A veritable history painting of social disintegration, this vision would have seemed extreme just a few years ago, but no longer.

Faith Ringgold, detail view of American People Series #20: Die, 1967. Oil on canvas. Two panels 72 × 144 in (182.9 × 365.8 cm).

However grim Die may be, Ringgold’s oeuvre also focuses on the accomplishments and aspirations of African Americans as well as on their travails. Family, motherhood, and community are persistent themes.

Ringgold has additionally pursued writing and teaching as vigorously as art, writing several renowned children’s books, while actively promoting other artists. All that Ringgold produces is of a piece with Black experience, which—despite being trapped in a maddening, never-ending gyre of progress and backlash—shoulders on.

Ultimately, the show brings us back to the question at the beginning of this review, if framed somewhat differently: Who gets to be counted among the American people? The ones who built and bled for a country that spurns them, or only those who feel ordained to own it? In a just universe, the answer would be obvious.