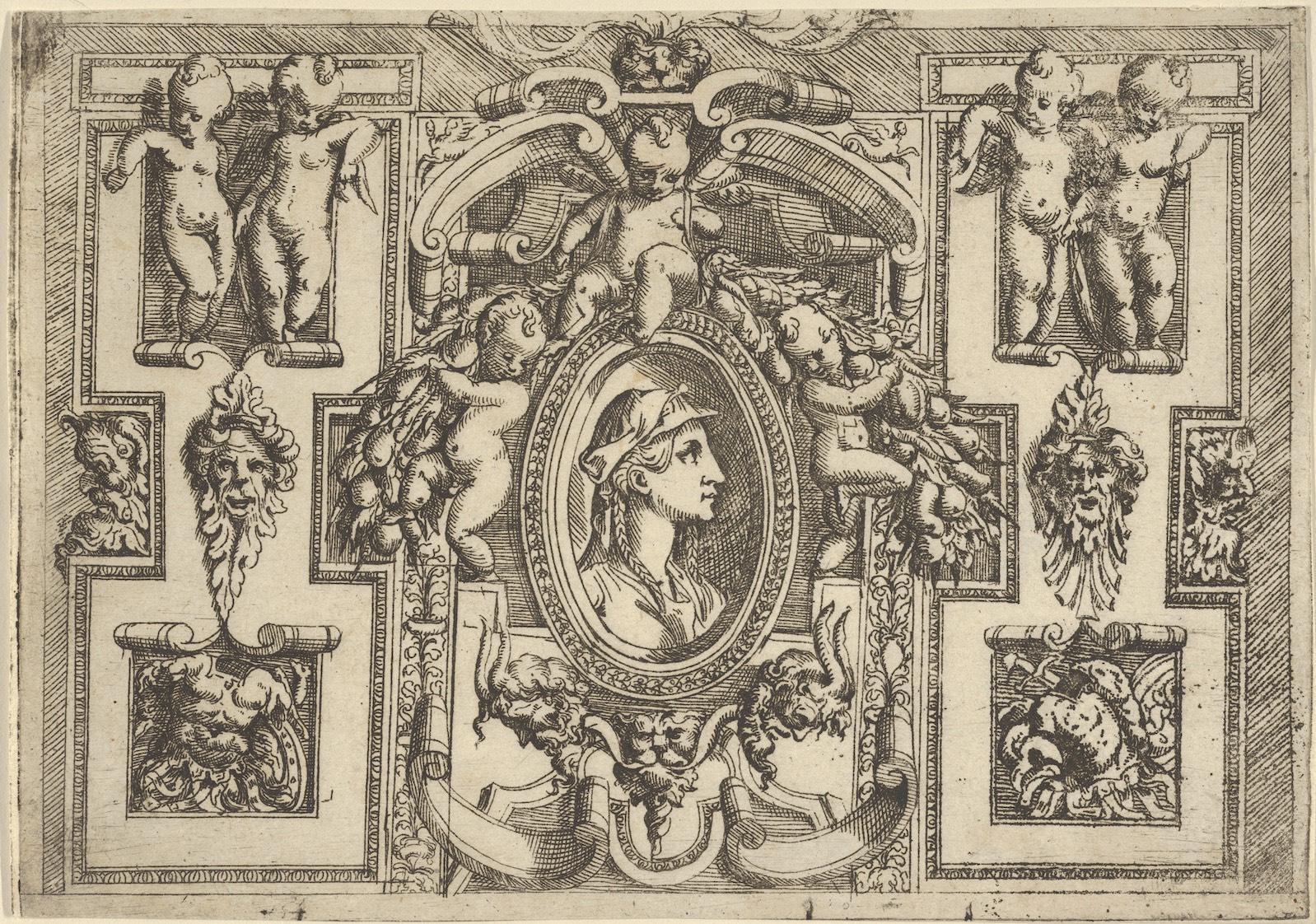

Deriving out of necessity to differentiate tableaus featured on walls and pottery, the sole purpose of frames was to behave as strict borders between reality and the imagined. Either painted or carved reliefs, these frames were the genesis of encasing history. As craftsmanship and carpentry evolved, frames shifted into the three-dimensional space with four main types of construction.

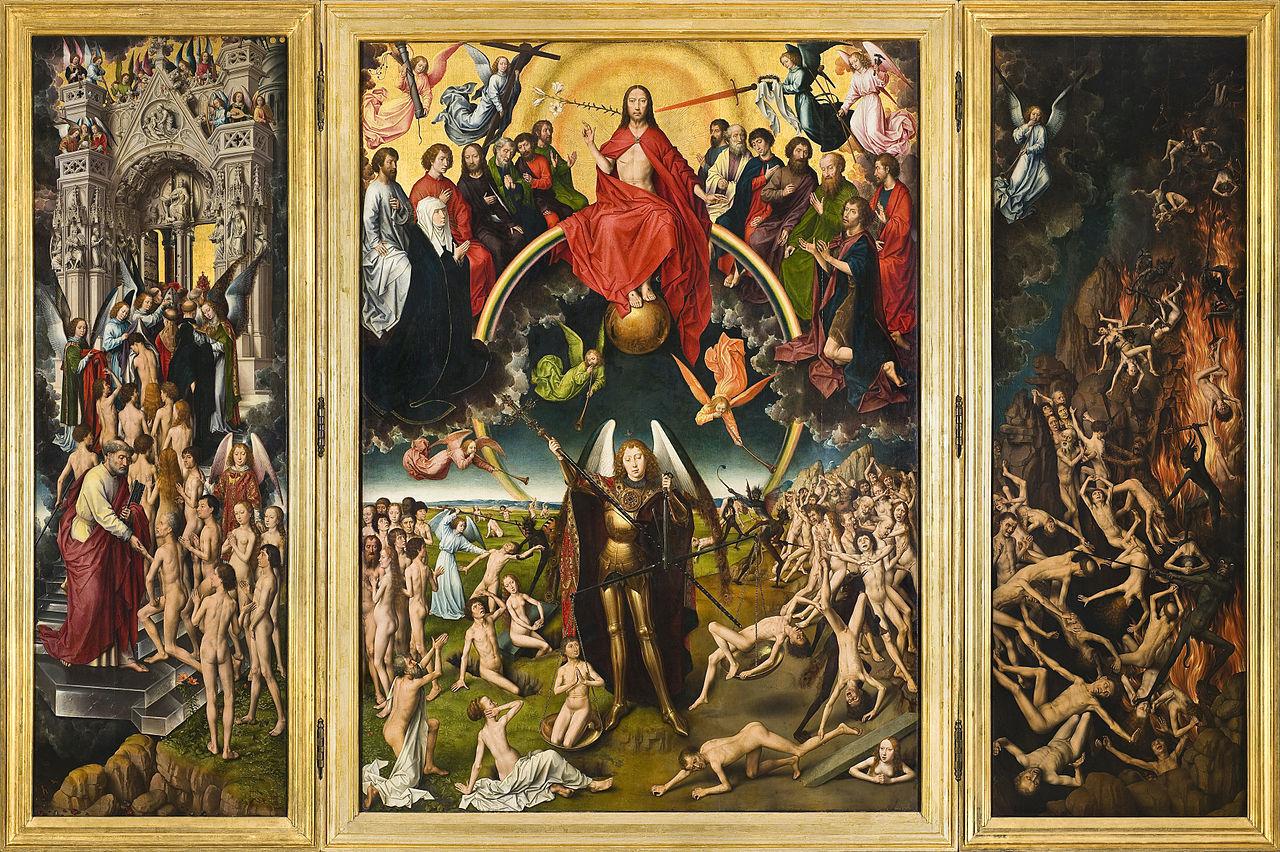

Akin to carved reliefs, integral frames were an all-in-one object that the artist would paint directly on. The practice can be spotted in Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and Child by a follower of Quinten Masseys.