Fortunately, many major research sites around the world have accelerated their digitization processes. While nothing compares to seeing works of art and original documents in person, the digital alternative can mean the difference between no access and some access to the materials that researchers need to consult. Digital collections can reveal the contours of works and shed light on what might be relevant and available someday for more careful consultation.

The main reading room at the Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building.

For art history doctoral students, writing a dissertation begins with extensive research. Students typically find the bulk of their original material in archives, museums, and libraries in regions where their academic interests lie. Conducting research in pre-pandemic times involved applying for grants to access these areas, and then learning to navigate each institution or site’s unique systems for finding material. Since COVID began wreaking havoc on nearly every aspect of life, “dissertation research” has taken on a new meaning for many pursuing PhDs in art history.

On-site research was put on hold abruptly in March around the world. Many students conducting their work while on fellowship-funded research years had to return home, their research paused awkwardly, without any clear idea of when they could resume their progress. Funding in the humanities is very often finite and sparse, so cutting precious research time short seemed disastrous to many students. Many fellowship programs are time-based, and losing months of on-site work might mean saying goodbye to the only funded opportunity to complete the dissertation. For some, losing months of funded research will require them to wait an extra semester or year to graduate without guaranteed financial support.

Oval room, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The Library of Congress' Thomas Jefferson Building.

But conducting an online search typically requires some knowledge of what they’re looking for; art historian Jennifer Wu explains that many digital resources are only useful when she knows exactly what she needs to consult. For students in the early stages of their research, the exploratory experience that comes from on-site discovery is often necessary for developing a unique dissertation topic based on objects that are sometimes unknown until they encounter them in person. Digital search engines and thumbnail images can’t mimic the experience of on-site browsing and of consulting with knowledgeable archivists in person.

Still, institutions like the National Library of France have developed extensive remote resources. The National Library of France’s Gallica database is an incredible storehouse of digitized photographs, entire books, magazine issues, and works of art. It’s free to consult from anywhere in the world, and has long served as a saving-grace for those unable to consult these documents in person. Even in pre-pandemic times, many researchers relied heavily on Gallica out of necessity: as original objects become more and more fragile, the library has become increasingly reluctant to release original copies to researchers onsite, directing them instead back to their laptops.

In the U.S., major sites like the Library of Congress, regional university archives, and public collections have shifted much of their focus to helping young researchers digitally. University librarians have provided invaluable help by scanning articles and books that are held in inaccessible libraries; doctoral candidates are finding that having a document scanned can make the difference between a research win and a missed opportunity. Public archives, such as the State Archives of Florida, are increasingly digitized, allowing students to conduct more of their work from home than they might have thought possible at the start of the pandemic. And individual archivists, employed at sites now empty of their typical visitors, have made themselves available for remote consultation.

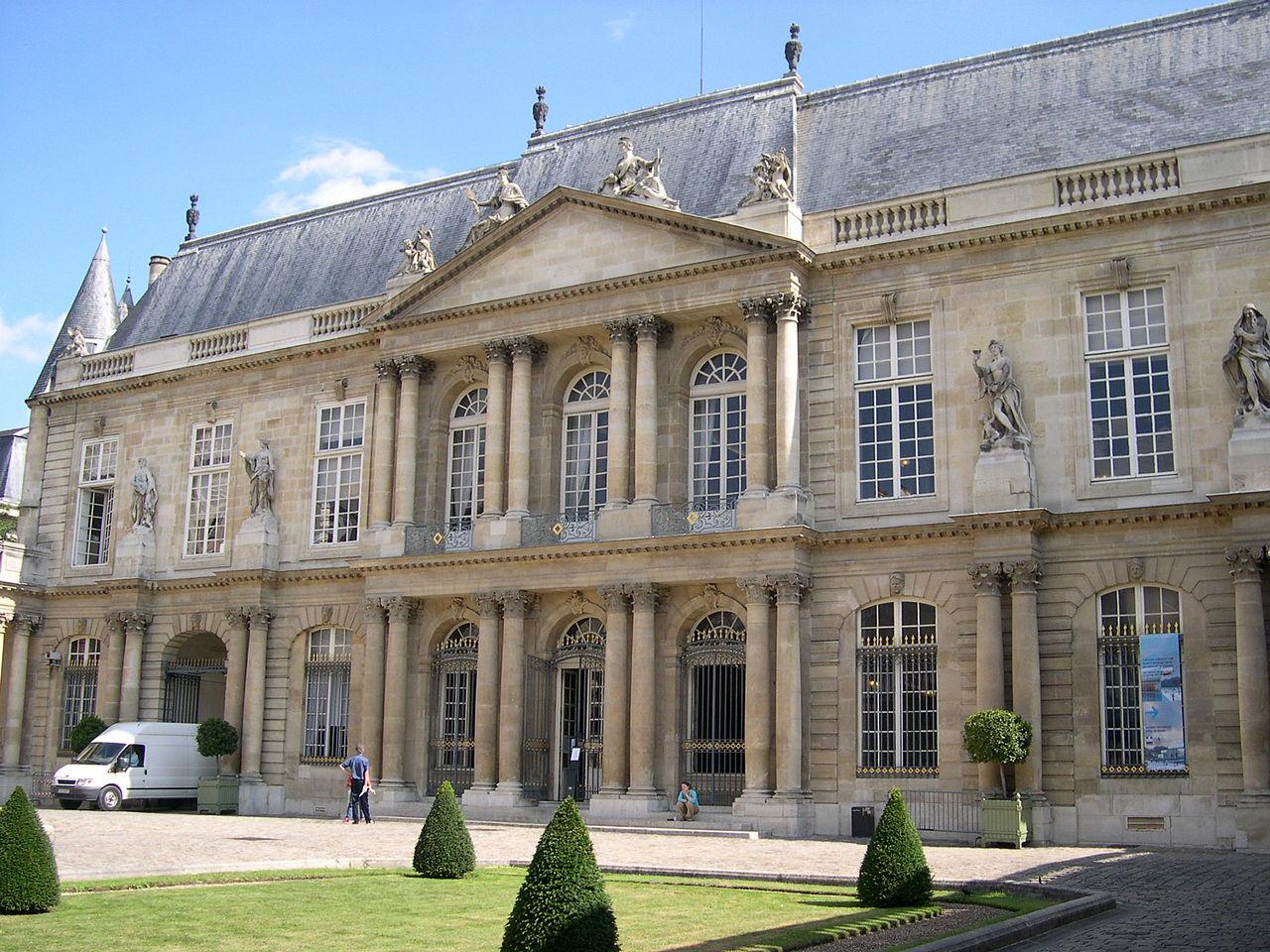

Archives Nationales de France.

Isaiah Ellis, a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says that he’s radically expanded his list of online archival tools, while having to postpone critical research trips indefinitely. With so much research happening online, the scope of his and many other students’ dissertations is changing accordingly. Prior to the outbreak, some found it difficult to keep a project at a manageable scale; limited access to resources now ironically makes the scope of some projects more tangible.

Art historians are used to having to justify the need for in-person research. Despite the increasing number of resources available online (often free of cost), a screen simply cannot replicate the experience of viewing a centuries-old manuscript, a massive painting, or a minutely-detailed print in person. Researchers often form their best ideas and make their most exciting discoveries while searching through uncatalogued materials or works on paper too delicate to scan. As research sites around the world slowly begin to reopen, art history students look forward to returning to them, ready to get back to work.