This presentation of watercolors at Zwirner uptown titled Tree of Knowledge serves as a follow-up of sorts to the Guggenheim’s survey, though it doesn’t quite pack the latter’s shock-of-the-new punch for obvious reasons: It’s a much smaller affair (just eight framed works on paper hung in a line), and af Klint is no longer an unknown quantity. However, as the gallery notes, all of af Klint’s oeuvre is held by a foundation bearing her name, with the exception of these examples, making them new to the public.

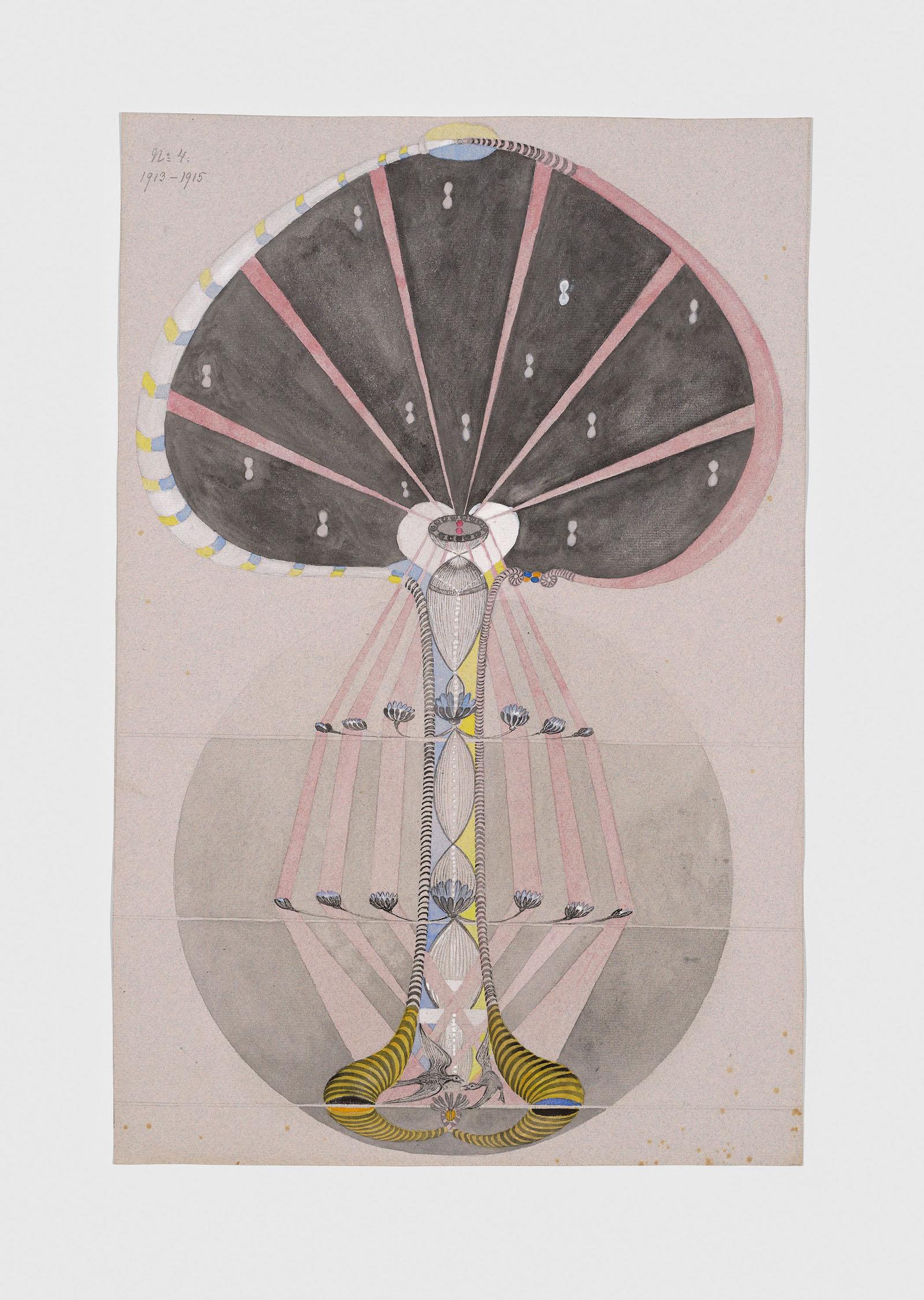

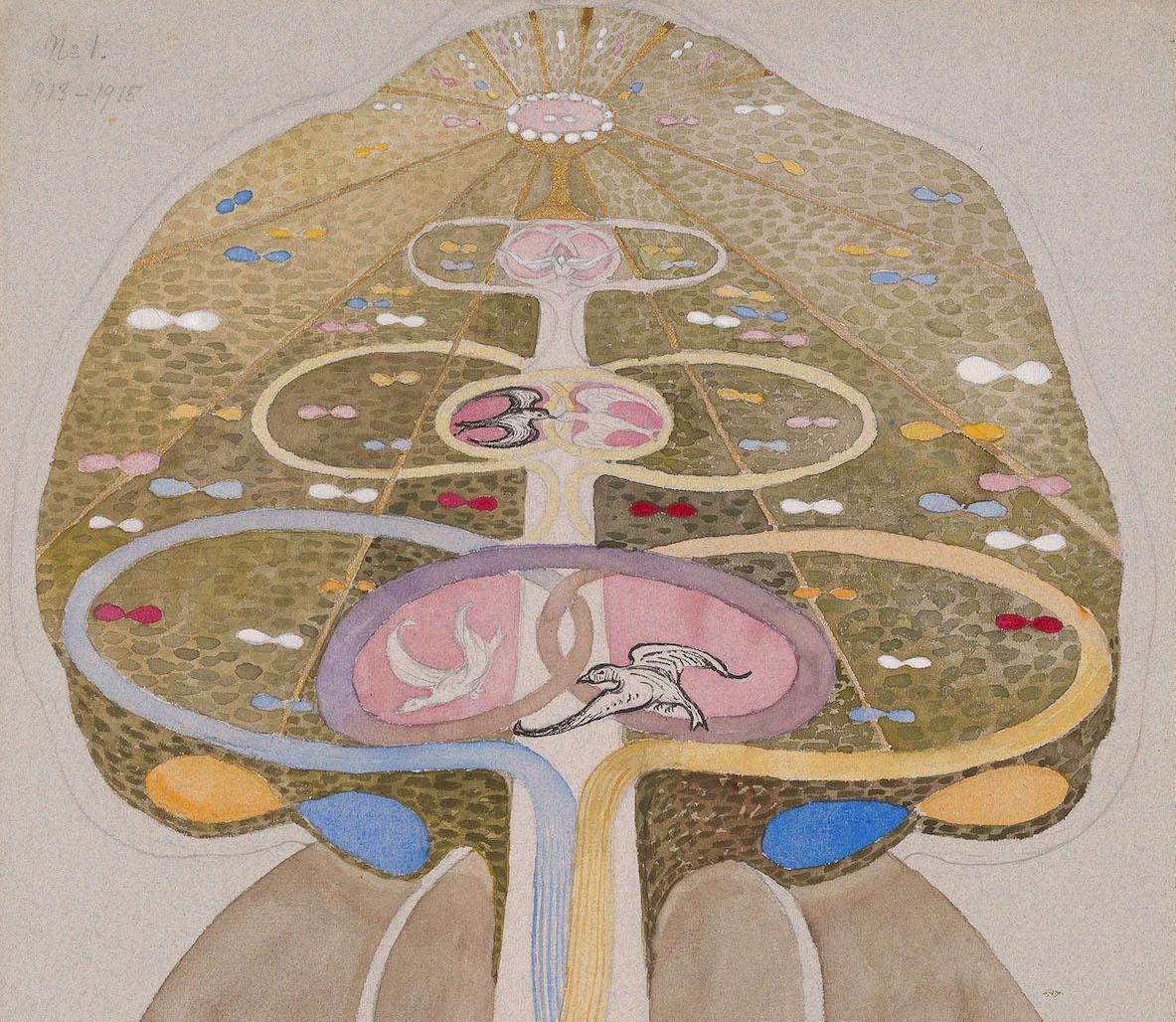

Hilma af Klint, detail of Tree of Knowledge, No. 1, 1913-1915.

The Swedish painter Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was a virtual unknown until a 2018–2019 Guggenheim retrospective resurfaced her career to wide acclaim. An overnight sensation more than 100 years in the making, af Klint stunned viewers with monumental, brightly colored abstractions created years before Vasily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian pivoted away from figuration, forcing critics to re-assess the history of the early twentieth century avant-garde. The show, which attracted more than 600,000 visitors and inspired a documentary about her life, immediately elevated af Klint to the ranks of iconic women artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Frida Kahlo, Louise Bourgeois, and Yayoi Kusama.

Installation view, Hilma af Klint: Tree of Knowledge, David Zwirner, New York, November 3–December 18, 2021.

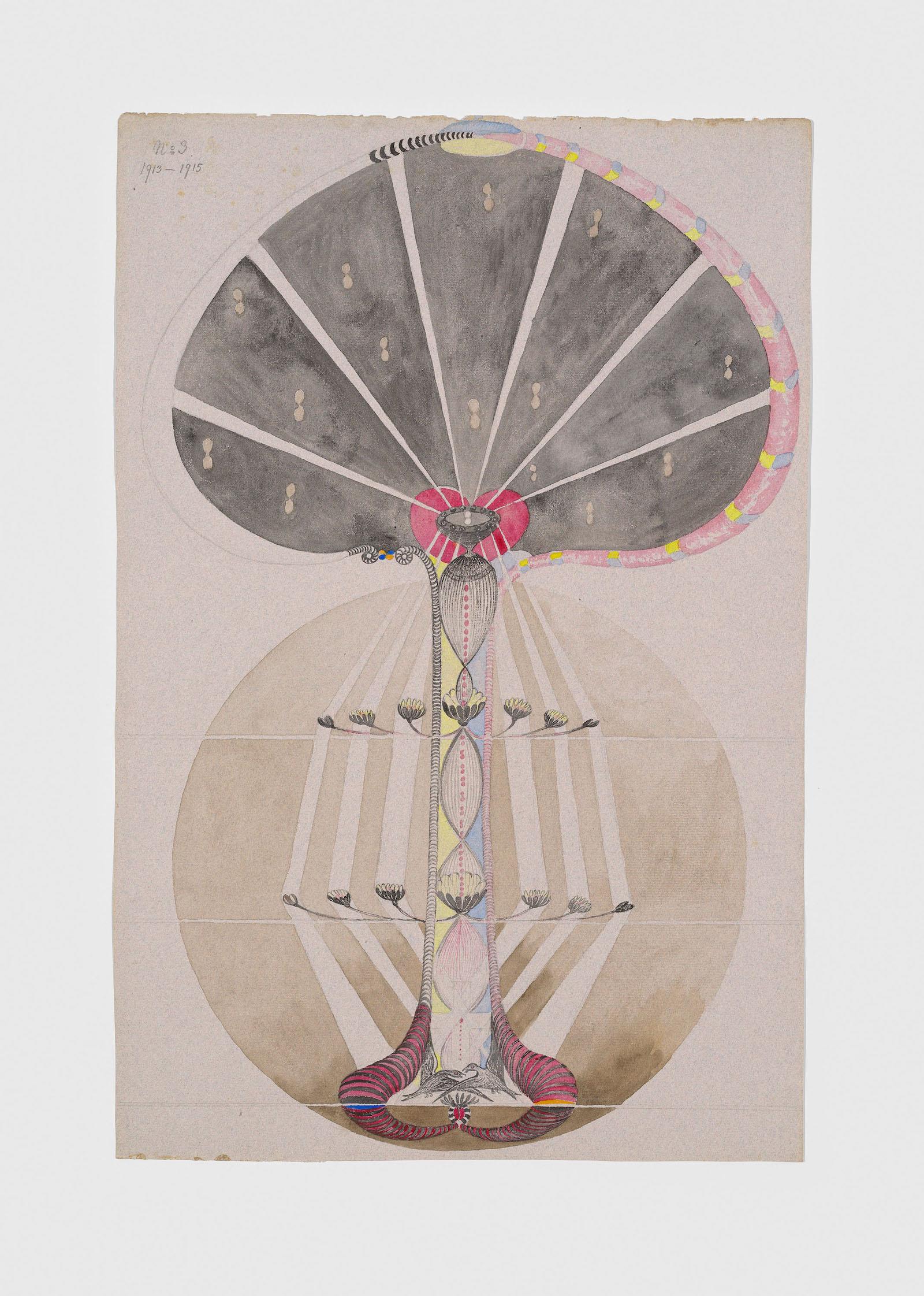

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No. 3, 1913-1915.

Like Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian, af Klint’s road to abstraction was paved with theories linking art to metaphysics, ideas that necessitated the development of totally new and non-objective approaches to painting. Af Klint’s own work was influenced by everything from Buddhism to the occult (she regularly attended seances, and for a while insisted that a mystical alter ego transmitted ecstatic visions to her), but she was particularly drawn to the writings of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), who posited that the spiritual questions and artistic needs of humanity could be addressed through the “science” of Anthroposophy—a discipline which he completely invented.

Af Klint originally created the Tree of Knowledge between 1913 and 1915, but it was only recently discovered that she’d actually painted another version of it, which is on view here. Gifted to Steiner by af Klint sometime in the early 1920s, the works were obtained after Steiner’s death by Albert Steffen, his successor as head of the Anthroposophy movement and an artist in his own right. They wound up in the collection of the Albert Steffen Stiftung in Dornach, Switzerland, where they remained until being unearthed.

The series specifically references Rosicrucianism, a sect devoted to plumbing hidden truths that predated Anthroposophy by several centuries. Among its teachings was the notion that the wood from the Biblical tree was somehow connected to the building of both Noah’s ark and the cross on which Jesus died. More to the point, the tree’s branches evoked different routes to enlightenment.

The images themselves measure roughly 18 X 12 inches and are rendered in lambent washes of pale color whose transparency lends them a spectral presence. Each piece comprises a vertical arrangement of forms suggesting the roots, trunk, and canopy of a tree growing out of a circular shape that evidently represents earth.

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No. 5, 1913-1915.

As the drawings are read from left to right, their composition becomes more and more stylized until it’s nearly abstract. Still, it is clear that God, or at least some semblance of divine revelation, is in af Klint’s finely drawn details, which depict an arcane symbology of birds, flowers, angels, and geometric patterns that resists interpretation even as it captivates the eye.

The Tree of Knowledge series, then, is consistent with an artist whose work was sui generis. Unlike her contemporaries, she never attempted to cultivate a movement around herself and her ideas. She worked alone, abjuring the epistemic closure of the group for an eclectic pursuit of cosmic verities.