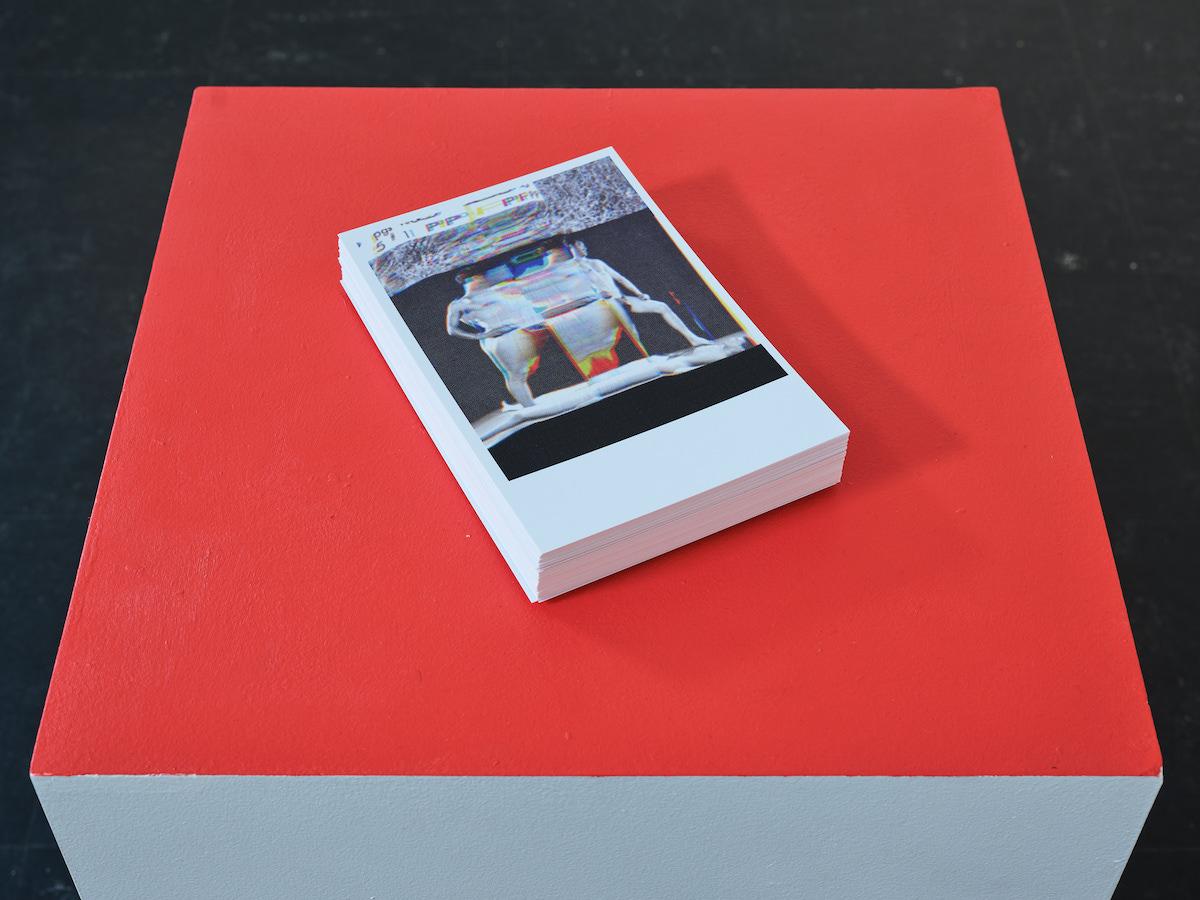

Rivera’s portraits are only six inches long, representing the intimate scale in which most of the artists in the show worked. Some of the works could be held in one’s hand, sit on a family’s mantlepiece, or hang above a desk. In their scale, the works by Rivera, Molina Garcia, Moreira, and Fifield-Perez all refuse an abstracted scan; they are meant to be looked at one by one, with sensitivity to their great depth and humanity. Yet with so much redacted information, the viewer actually cannot access all of the artworks’ context. “They’re building a beautiful refusal,” says Donoso. Legibility, here, is not the priority.

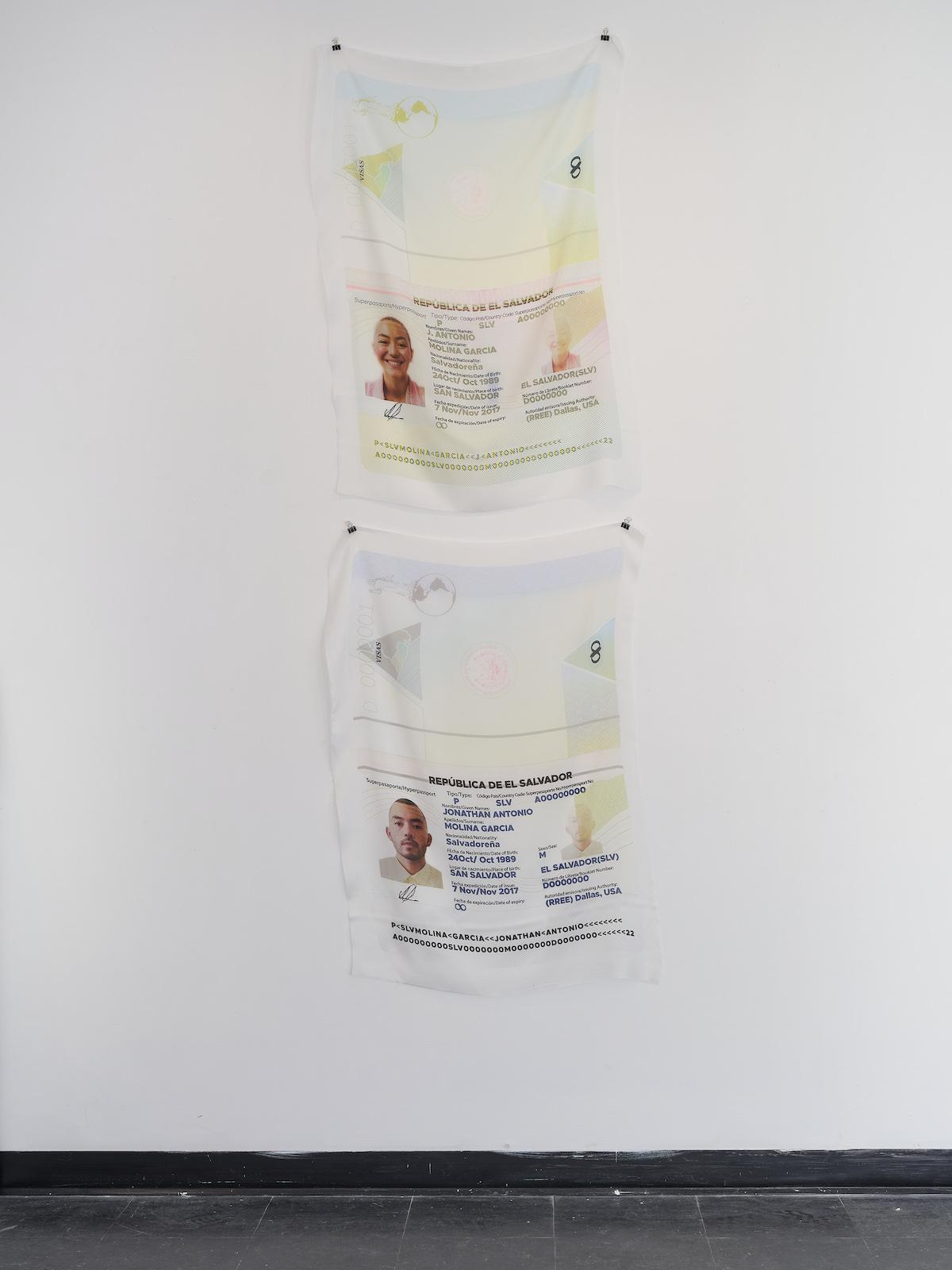

The various artists’ practices challenge the surveillant gaze by staring back at the structures that consistently demand they explain themselves. What comes out very clearly is that the language of power is not always vibrant or overwhelming. Its color palette is bureaucratic, innocuous, bloodless, and muted. It is meant to bore and, inherently, to flatten out the people who engage with it. These artists subvert the visual language of power not just by co-opting it, but by infusing it with real meaning, aesthetic interest, and their ever-changing selves.

“Utopia and hope aren’t a far-off land or a fool’s errand of idealism and romanticism,” says Garcia. “We are, in ourselves and together in the communities that we belong to, pockets of real, actualized hope.”