Many of the posters were collaborative efforts between an artist who designed the composition, an illustrator tasked with rendering the imagery, and the printing technicians who produced the final chromolithographs. Posters are highly complex items, and historically have been made by blending fine arts techniques with “low-brow” forms of cultural production. The resulting objects are entirely unique; that posters are displayed now in a museum setting indicates how perceptions of them can change depending on the setting in which viewers encounter them. In the Art Gallery of Ontario, the posters are dignified and celebrated for their expressive and aesthetic merit.

Adolph Friedländer, Le Roy, Talma, Bosco: World’s Monarchs of Magic, 1905.

Viewers confront a golden age of North American entertainment through a nuanced and sensitive twenty-first-century lens in Illusions: The Art of Magic, on loan at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from the McCord Museum in Montreal. The exhibition presents dozens of beautifully-preserved posters from approximately 1880 to 1930 that advertise magicians and their feats of incredible illusionism. Illusions celebrates the poster form in all its expressive potential, while shedding light on how advertising, promotional chromolithographs, and other forms of popular media can inform present-day viewers about late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century leisure practices and cultural beliefs.

Many of the works displayed are chromolithographs, a printing technology developed in the late-nineteenth-century that produced full-color lithographic images. According to Christian Vachon, the head of collections management at the McCord Museum, the most significant challenge that the exhibition presented to curators was the sheer size of some of the posters on display. Many works are impressively large; matting and framing promotional-sized chromolithographs as large as nine feet tall was daunting. Yet Vachon is adamant that the unwieldy size of the works was a small price to pay for the uniqueness of the exhibition.

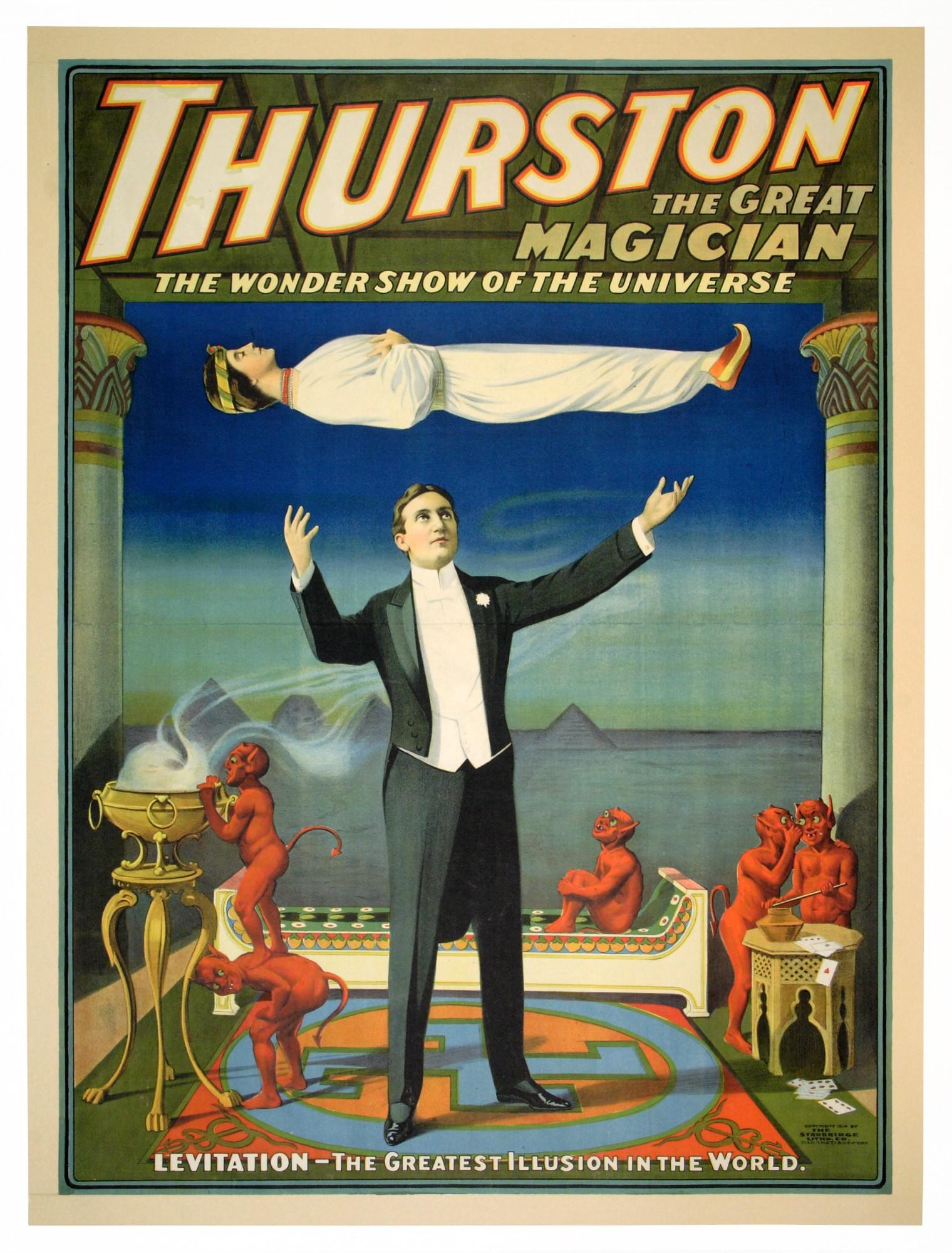

Strobridge Lithographing Co., Thurston: Levitation – The Greatest Illusion in the World, 1914.

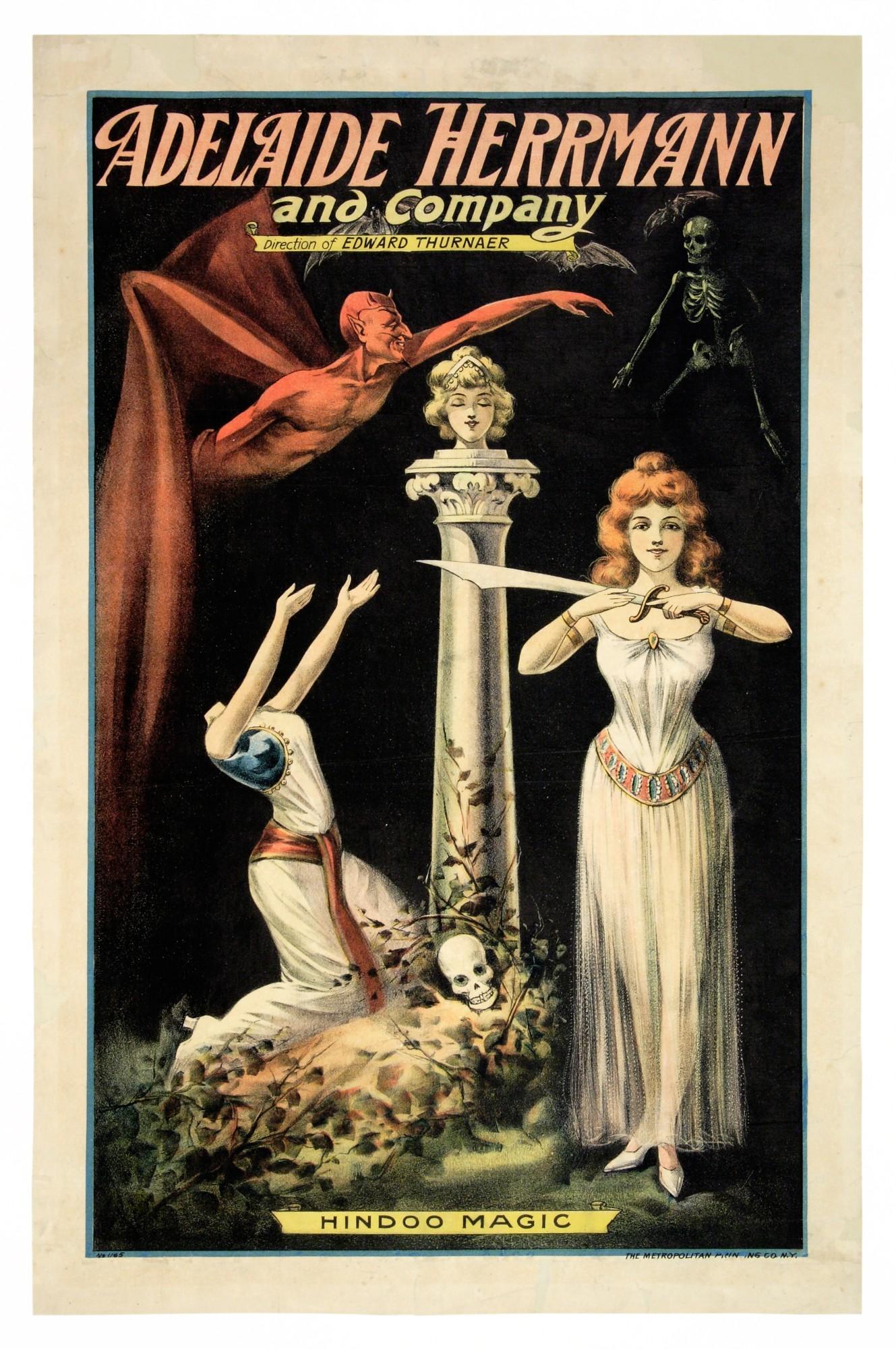

The Metropolitan Print Co., Adelaide Herrmann: Hindoo Magic, c. 1900.

In putting together the show, Vachon and the exhibition’s curators noticed that many of the posters feature women. The exhibitors address how the female body was used as titillation and enticement in many of the promotional posters: male magicians often manipulated passive women’s bodies and inflicted illusions onto female assistants, reflecting a power imbalance that seems troubling to contemporary standards. A 1914 poster advertising magician Thurston’s Levitation: The Greatest Illusion in the World shows the white male magician seemingly raising a passive and elaborately-dressed young woman above observing devils.

Yet many of the women on posters are not simply allegorical, or even depictions of assistants. Vachon notes that audiences have responded especially positively to portraits and posters of actual historical female magicians such as Adelaide Herrmann and Miss Marianna De Lahaye, and to the fact that many of these female magicians managed their own businesses. The curation reveals that there were some (albeit few) women who pioneered more progressive gender roles in the realm of magic entertainment.

Charles Lévy, Miss Marianna De Lahaye: Magic & Illusion, c. 1898.

Presenting exhibition material that reveals outdated cultural biases, stereotypes, and beliefs can be challenging. The curators of Illusions manage to demonstrate ideas and items that were considered acceptable and entertaining in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries while carefully contextualizing the cultural environment in which the posters were produced and received. Works that feature racial and cultural stereotypes are grouped carefully in a section of the exhibition titled “Cultural Appropriation in Magic” that makes clear that these views were considered acceptable at the time the posters were first printed.

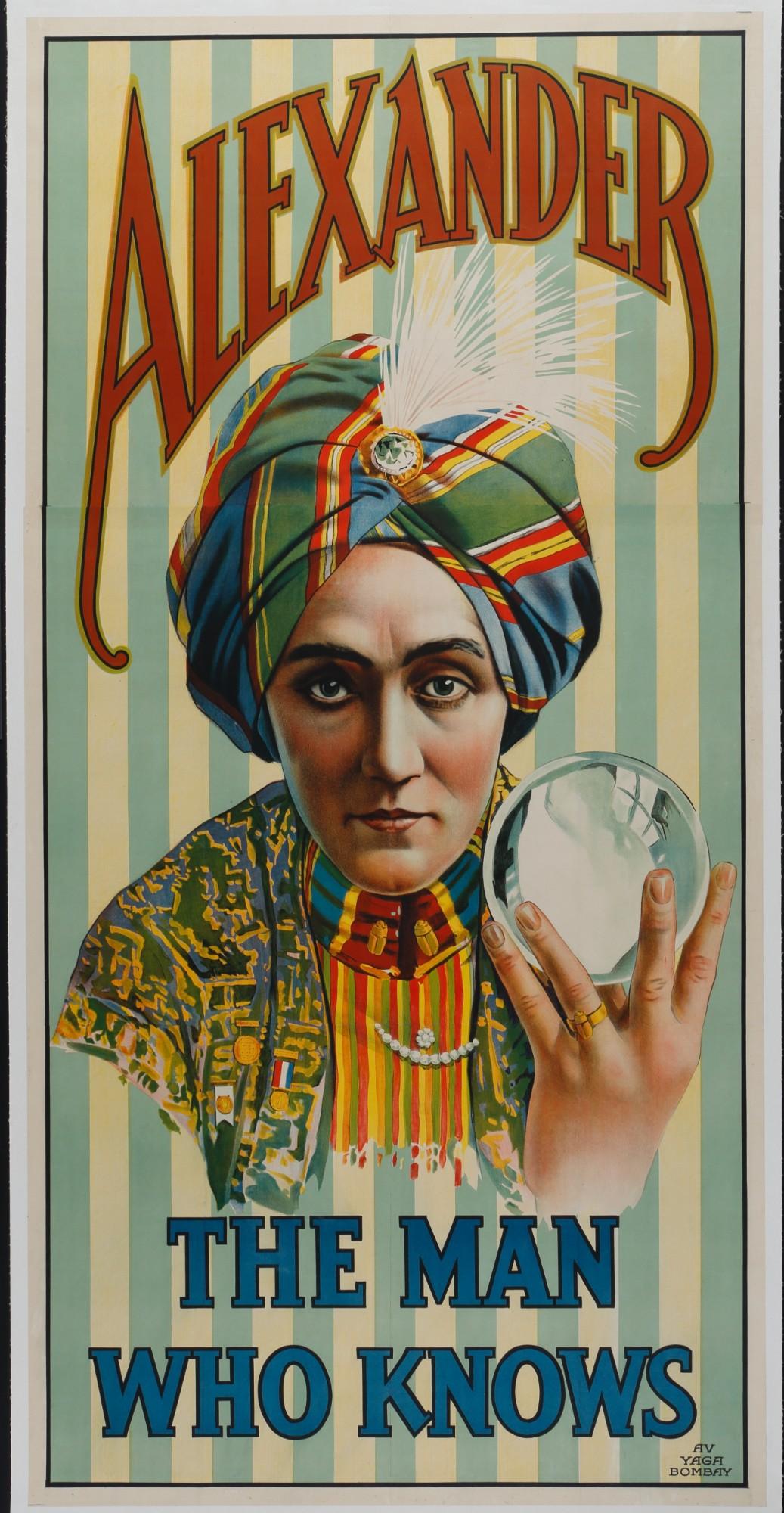

Av Yaga Bombay, Alexander: The Man Who Knows, 1915.

For example, designs and décor derived from ideas about Eastern cultures were trendy in the late 1800s in much of North America at a time when Chinese immigrants were barred entry to the United States: a fact that reveals the hypocrisy and racism that informs many of the posters displayed in this particular section. A 1915 poster advertising “Alexander: The Man Who Knows” portrays a magician dressed in a turban, holding a crystal ball, suggesting that Eastern identities were associated with mystery, exoticism, and clairvoyance. The considerate wall text explains how cultural appropriation was used in magic shows and their associated posters, providing important historical background to works that appear startling to twenty-first-century viewers.

The McCord is a social history museum, and Vachon says that the McCord’s visitors are accustomed to encountering a wide variety of materials and content when they visit. Seeing the collection of posters in the AGO—Toronto’s largest and arguably most well-known art museum—reinforces how popular culture items can broaden understandings of what constitutes art museum content, while revealing some of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century’s cultural biases and beliefs.