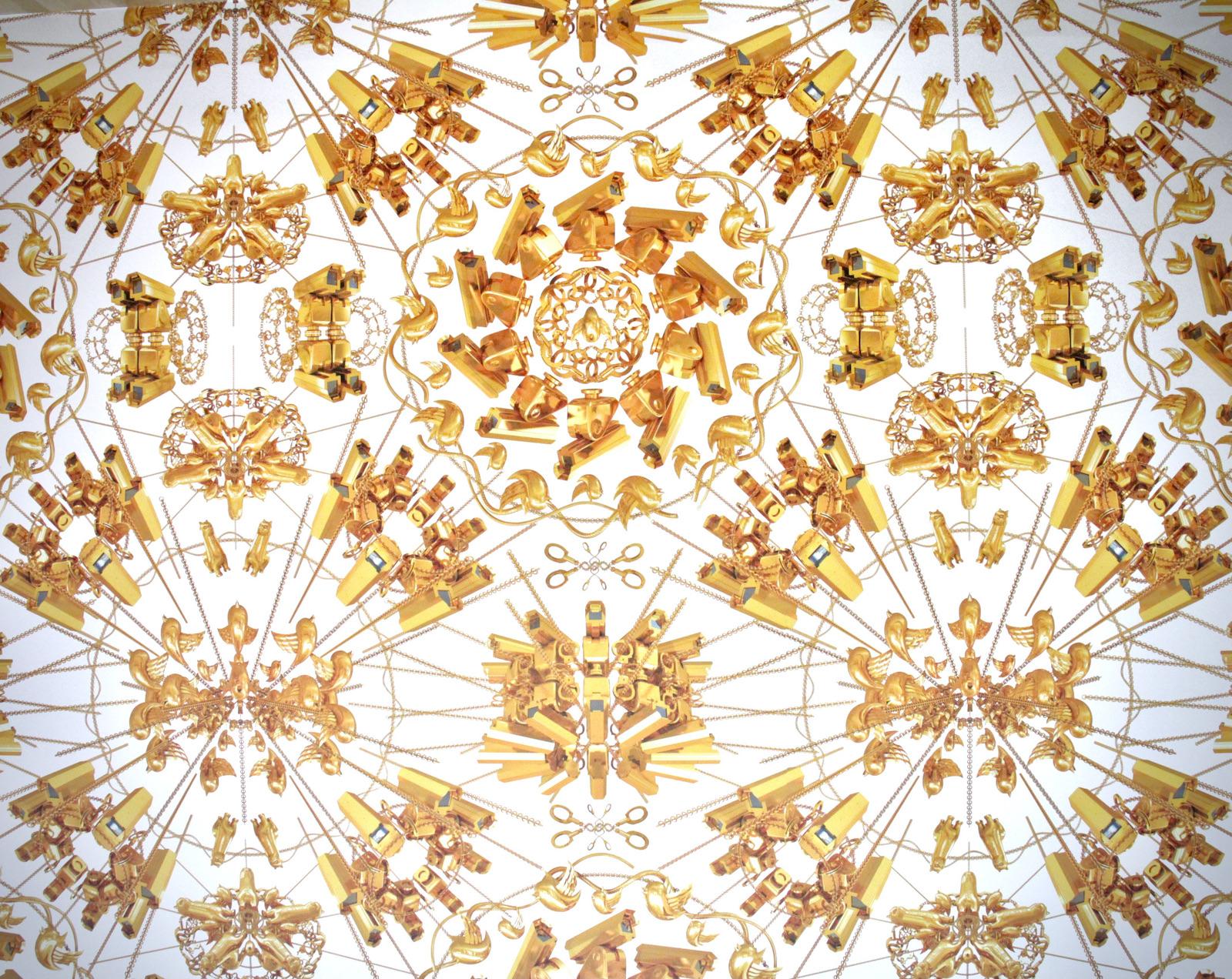

This turbulent passage in his life is reflected in Trace, LEGO likenesses highlighting brave figures like Seng-Aloun Phengphanh and Thongpaseuth Keuakoun, members of a Laotian student pro-democracy group sentenced to twenty years for hanging posters. Also included are familiar faces like Edward Snowden, Nelson Mandela, and, problematically, Aung San Suu Kyi, whose public image has shifted since the show first exhibited, appropriately enough, at Alcatraz Island in San Francisco in 2014. It has since traveled to D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum and now through August 1 is at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center in a version scaled down from 176 to 83 portraits covering the floor of a gallery wallpapered with The Animal That Looks Like a Llama but Is Really an Alpaca, a pattern mixing surveillance cameras, alpacas (an internet meme for freedom of expression in China), and the Twitter logo, (look closely for the artist’s self-portrait).

Installation View of Trace featuring the artist's portrait at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center.

In 2009, artist and activist Ai Weiwei suffered a cerebral hemorrhage when he was beaten by police for attempting to testify on behalf of fellow activist Tan Zuoren. Two months before his arrest in 2011, Ai’s Shanghai studio was bulldozed. He then spent eighty-one days in jail before authorities acceded to global protests and released him. When his passport was reinstated in 2015, Ai fled China and has lived abroad ever since.

Installation View of Trace at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center.

“I think anybody who makes a conscious decision to fight for ideology, they're quite conscious it will cost them. Going back to China, I had to ask myself what’s the worst that can happen? I end up in jail,” Ai tells Art & Object about his decision to return to the country, despite being persona non grata. “I thought, yeah, I can take that. It was easy thinking it, but not in reality. While you’re being put in jail you realize what jail looks like. In jail there are certain conditions where you wish to die rather than to stay alive. Basically, you use life to punish life. So, everything in jail is against the essential meaning of being alive.”

Working on Trace with Amnesty International, a list of activists was compiled, but Ai found many of their likenesses blurred or pixelated. So, taking a cue from his son’s toy box he turned to LEGO bricks to approximate the effect. Unfortunately, he found them in short supply when the LEGO company informed him of their policy against using the toys for political purposes. In response, as he has so often in the past, Ai turned to social media and soon found himself flooded with LEGOS from most corners of the globe. In the end, the Danish toymaker abandoned their policy.

Detail of Portraits in Installation View of Trace at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center.

Since Trace’s debut in 2014, there’s been a rise of authoritarianism in China, a country ranked 176 out of 180 (a few notches above North Korea), in the World Press Freedom Index published by Paris-based Reporters sans Frontières (RSF). In the report, President Xi Jinping is called "the planet's leading censor and press freedom predator" for stifling speech in China as well as Hong Kong where fifty-three student protesters were arrested earlier this year, and Apple Daily publisher Jimmy Lai was recently sentenced to eighteen months.

“It’s the end of Hong Kong. Like Shanghai or Shenzhen, Communist China needed it for foreign currency investing. Now, China doesn't depend on it anymore. All the western investment and money can go through Beijing and Shanghai,” says Ai, whose documentary on the subject, Cockroach, came out last year. “The take on Hong Kong is two words, Taiwan. Principally the Chinese Communist Party has a clear vision – they want one state, unify China. Of course this is very difficult. Taiwan has been independent.”

Installation View of Trace at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center.

Not just on the rise in China, authoritarianism has eclipsed democratic voices in Brazil as well as former Soviet states like Poland and Hungary. Nationalist movements have moved from the fringe to mainstream among U.S. allies like France and Germany and even at home, where on January 6, Trump supporters attempted to overrule voters and install the failed despot for at least another term.

“I’m not really surprised. I read my history,” Ai says about democracy’s backslide in recent years. “When we look back at decades of peaceful and democratic movements, it's only very temporary. So, I think there could always be one solution, and those solutions are a political movement. It always takes a movement to defend certain values. If we give that up, that can easily turn to dictatorship.”

The exterior of the US Capitol Building on January 6, 2021.

Ai Weiwei and his family suffered the effects of dictatorship early on when his father, poet Ai Qing was sent to the rural northwest during the Cultural Revolution, part of Mao’s effort to consolidate power in the 1960-70s. Formerly a University Professor, his father was “reeducated,” leaving the family in poverty. In 1978, Ai returned to the capital to study animation at the Beijing Film Academy. He soon became a founding member of the early avant-garde art collective "Stars," composed of practitioners like Ma Desheng, Qu Leilei, Ah Cheng, Wang Keping, Li Shuang, Mao Lizi, and Huang Rui.

From 1981 to 1993, Ai studied and practiced in the U.S., mostly in New York City. Returning to China to be with his ill father, he joined the experimental artists' collective, Beijing East Village. His self-designed studio/house led to his founding the architecture studio FAKE Design, which was tapped to build the Beijing National Stadium, commonly called the “Bird’s Nest,” co-designed with Basel-based Herzog & de Meuron. The CCP was intent on creating a first world, globally impressive display for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, particularly opening night, the ceremonies of which were directed by award-winning filmmaker Zhang Yimou and featured the fireworks of artist Cai Guo-qiang.

The Beijing National Stadium, also known as "the Bird's Nest," built for the 2008 Summer Olympics.

Although the Bird’s Nest was the pride of Beijing and probably the most photographed structure of the games, Ai quickly fell from favor when he publicly criticized the Party’s propagandistic handling of the celebration. Beijing will host another Olympic games in 2022 and, amid a trade war with the U.S., there’s been talk of a boycott.

“The Olympics, basically, has already lost its original meaning. It’s a business opportunity, and we all know that,” says Ai. “Can the world boycott China? I don’t think that can happen. Today, it’s not clear who’s China or who’s United States, or whatever. It’s all mixed on a corporate level.”

Detail of Portraits in Installation View of Trace at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center.

Ai will be watching from his home in Portugal by the sea. Rested but seldom complacent, he enjoys the food and the ocean and being with his family away from persecution. He remains sanguine in the face of rising authoritarianism, but to do so is a daily struggle. “I’m optimistic about life itself,” he sighs, “but I’m not very optimistic about human development.”