Most critics call Juliano-Villani’s work “irreverent” due to its disregard for traditional boundaries, but in doing so, they overlook the deeper exploration of societal norms, cultural symbols, and the absurdity of the human experience that defines Juliano-Villani’s voice. The show quite literally opens with this notion of irreverence with a full-length double portrait of the artist herself, standing in front of a young and handsome Elvis Presley, her hand palming Elvis’s crotch. They stand against a pink, ethereal background. It’s quick, to the point, bizarre, and so photo-realist, it looks like the artist asked AI to create the image.

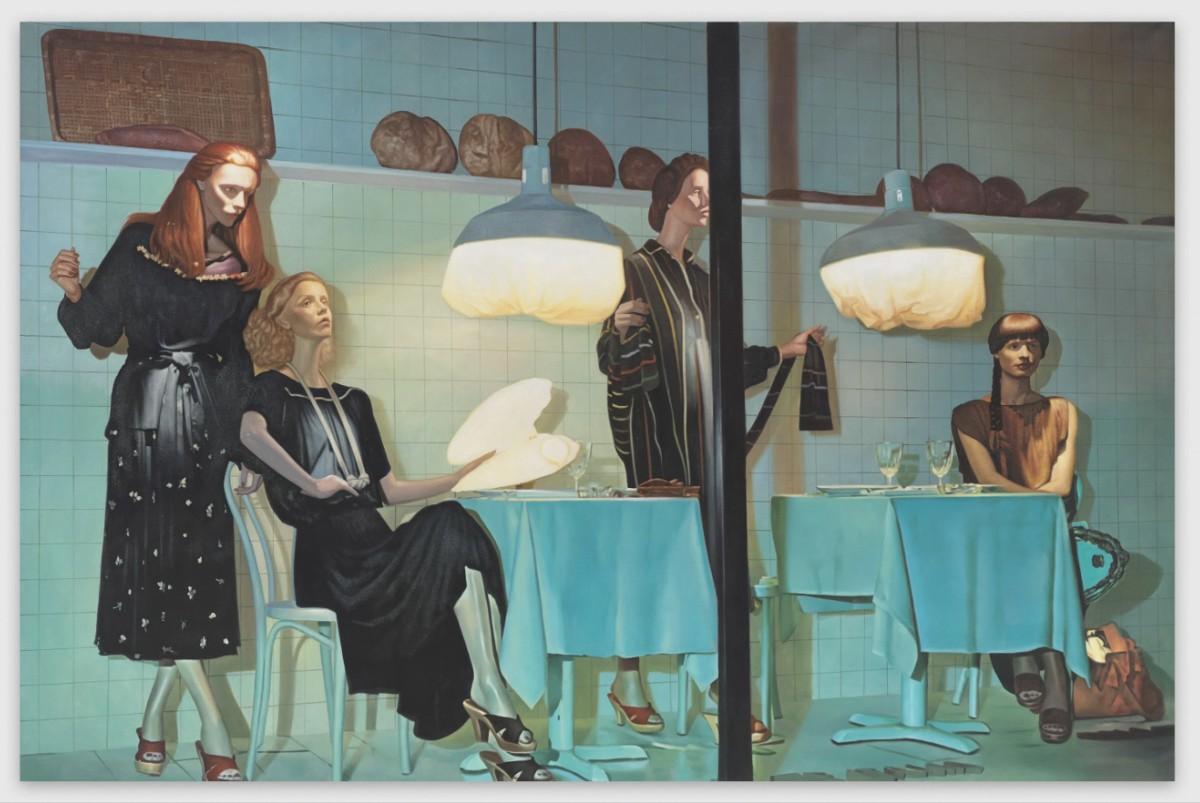

On the opposing wall is a massive, double image of Jean-Michel Basquiat sitting in a red chair. It evokes Andy Warhol’s screenprints of socialites and celebrities, made obvious by the subject and the repeated image, but it also speaks to the media-driven narratives that shape our perceptions of artists. Basquiat wasn’t just known for his art, but for his personality, his friends, and his exposure on the scene.

“I still don’t really care that much about Basquiat, but I respect and relate to the cult of personality thing," Juliano-Villani told Cultured Magazine in an interview. "It’s also a pastiche because all artists are kind of like props of identity. I know that’s what I’m being used for.”