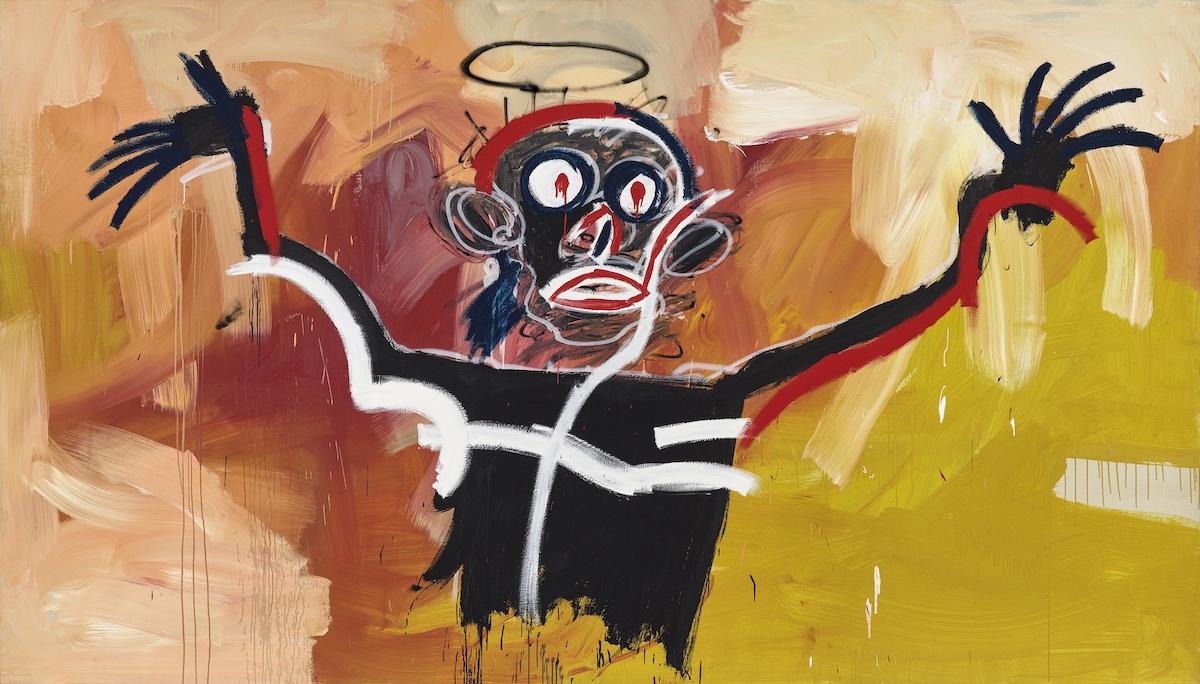

Meanwhile, in Basel, Switzerland, the solo show "Basquiat. The Modena Paintings" at the Fondation Beyeler (June 11 - August 27, 2023) offers a suite of eight large-scale paintings that the artist made in the Italian city of Modena over a two-week period for a 1982 exhibition that never took place—until now, more than 40 years later.

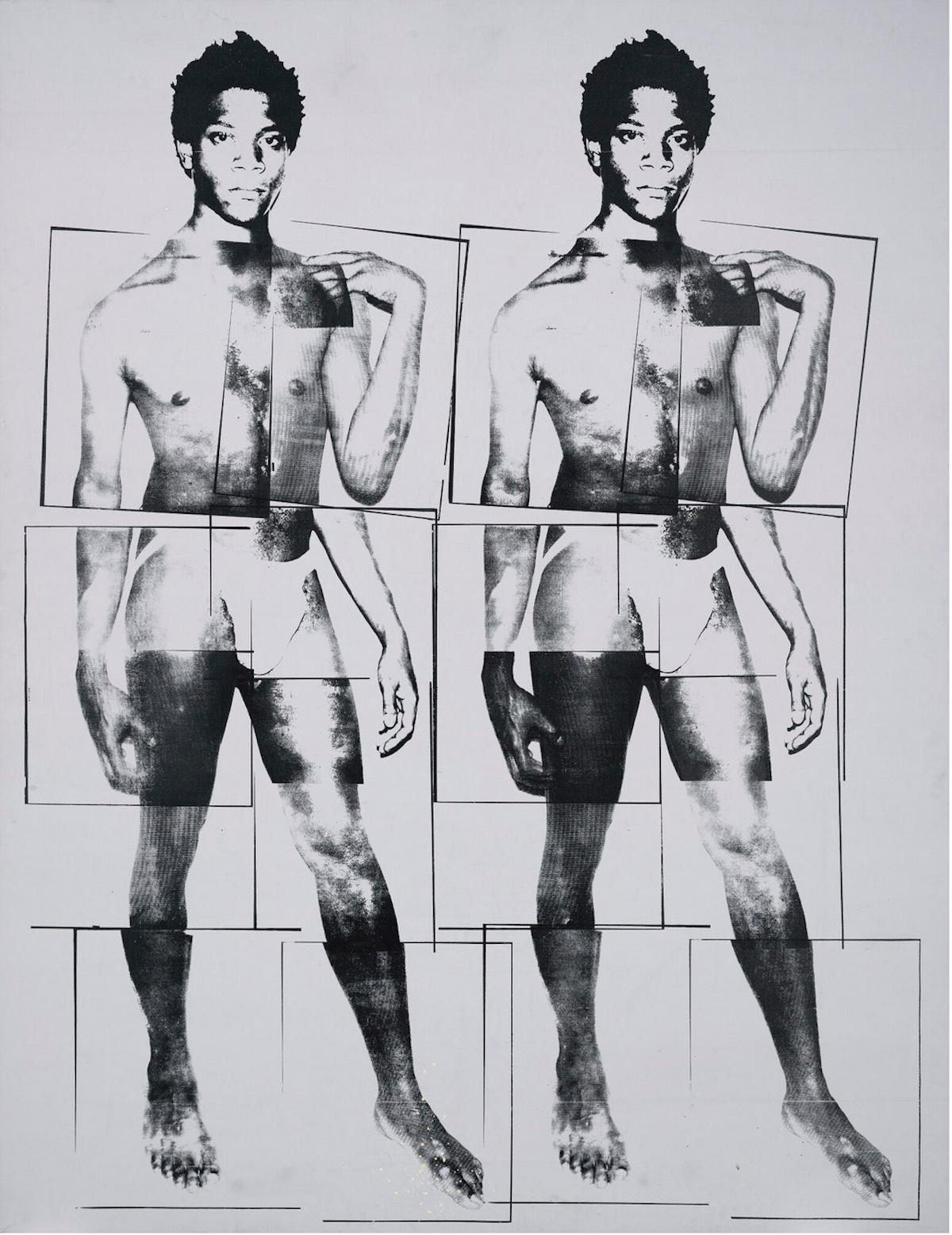

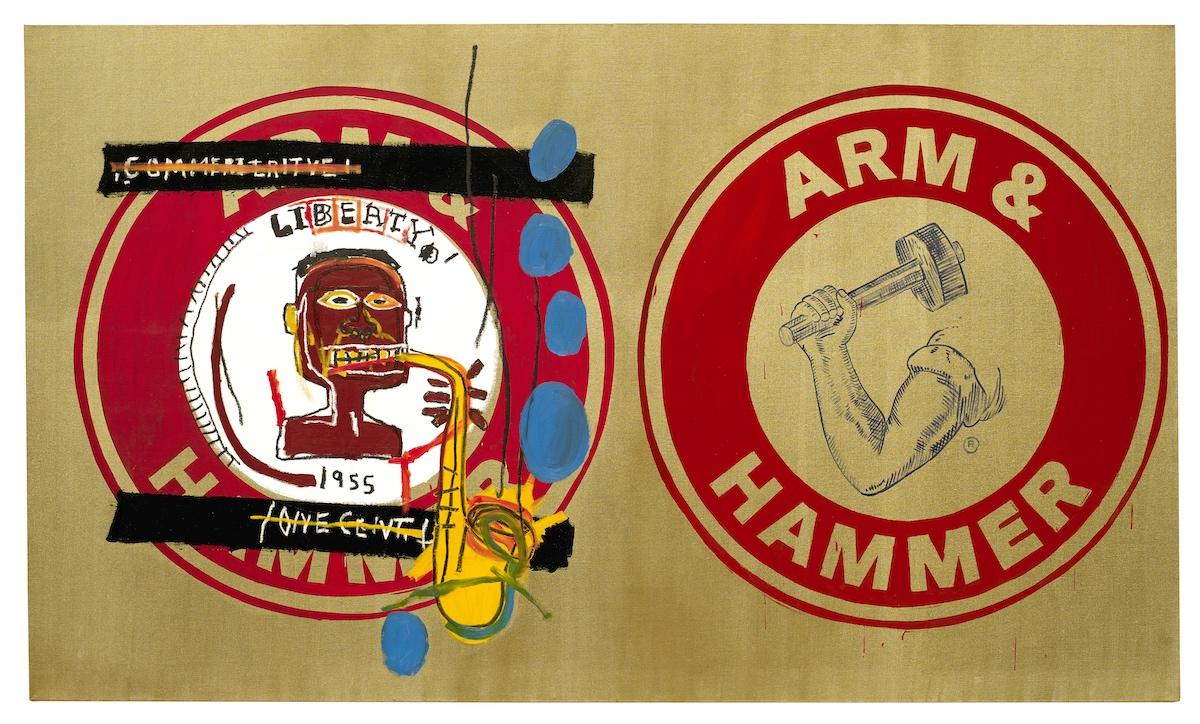

After seeing a selection of the Basquiat/Warhol collaborations in a much-anticipated exhibition at New York’s Tony Shafrazi Gallery in 1985, where 16 of the paintings were shown for the first time, Keith Haring appropriately called the visual dialogue, “a conversation occurring through painting, instead of words.” Bruno Bischofberger, the Zurich-based megadealer who represented both artists, had initiated the collaboration between Basquiat, Warhol, and Clemente. He thought of it as a contemporary version of the Surrealist’s exquisite corpse collaborations, and as a way for the elder Pop artist to engage the gallery’s younger artists. Bischofberger also saw the collaborations as a means to stimulate Warhol’s weakening market, as his previous body of dollar-sign paintings had, ironically, failed to find many buyers.

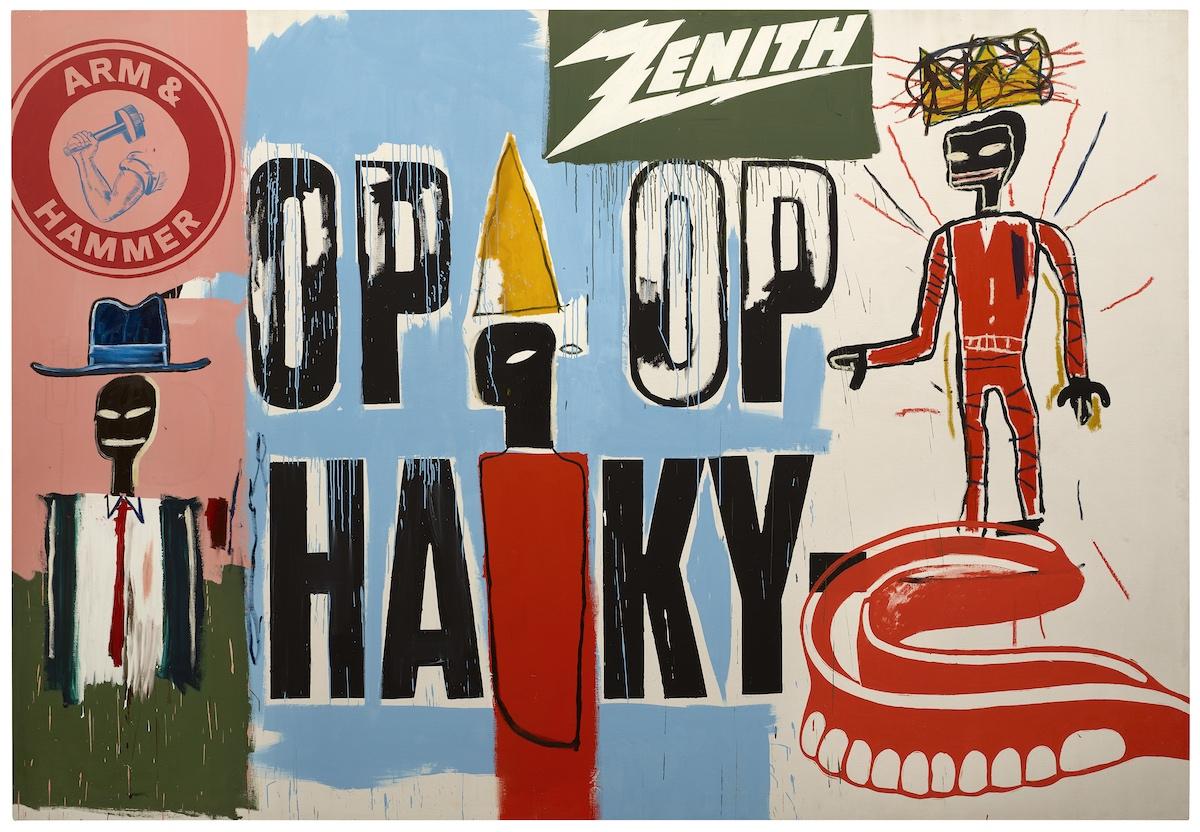

After completing the three-way works, Basquiat and Warhol continued collaborating—initially doing small works together before turning them into an almost daily production on a grand scale after a move of the Interview magazine office out of the Factory created more studio space. According to friends and staff who saw the paintings in process, including Paige Powell, a Warhol assistant and Basquiat’s girlfriend at the beginning of the collaboration, the two artists would take turns painting—often working on canvases several times in succession.“He [Warhol] would start most of the paintings," Basquiat told Tamra Davis and Becky Johnston in a taped 1985 interview. "He would put something concrete down, a newspaper headline or a product, and then I would sort of deface it and then would try to get him to work some more on it. And then I would work more on it.”