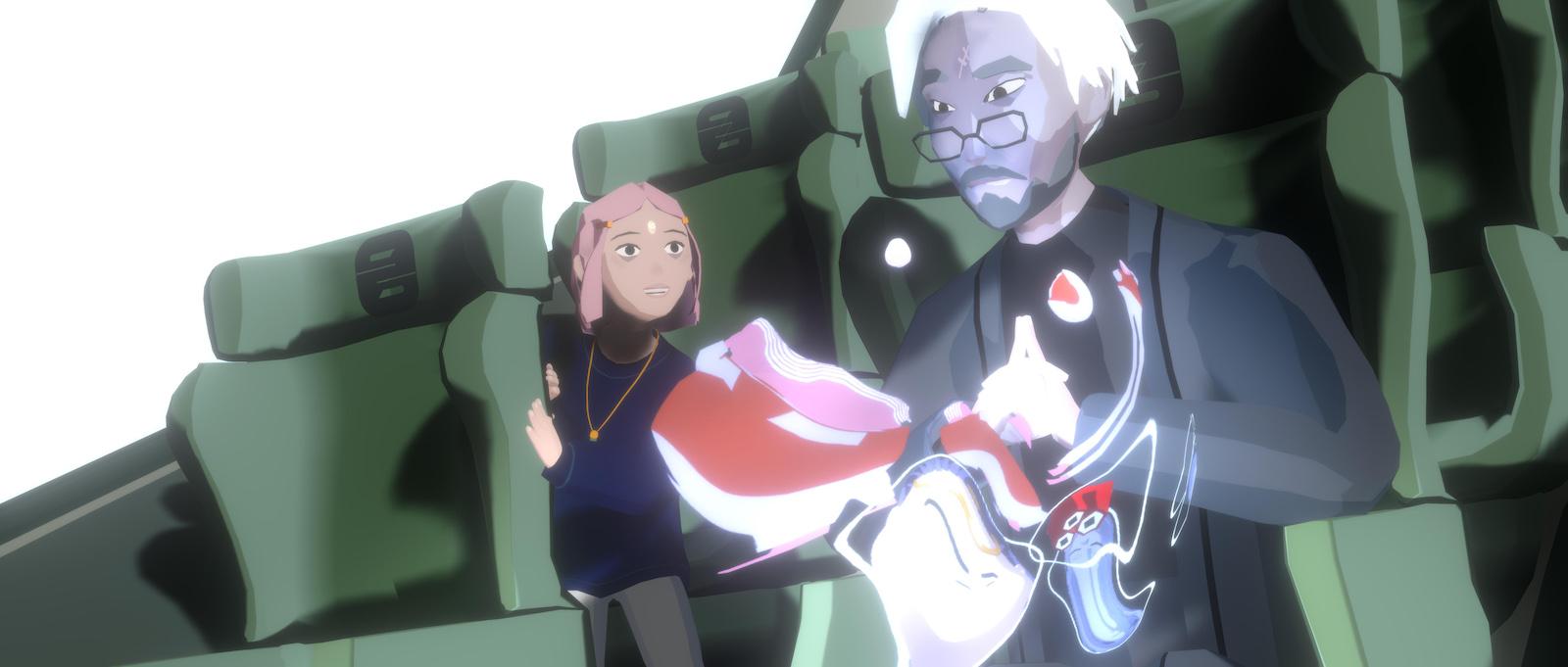

That would be Dr. James Moonweed Wong, a developer working for Zoroaster Immeasurables (ZIM), a “neural AI life path company,” as the exhibition’s wiki page explains, that produces “wetware”—applications that plug directly into the body through the titular B.O.B. (Bag of Beliefs), a kind of metallic worm engineered by Wong to merge with the spinal column. Its most sophisticated iteration, the Destiny B.O.B, can take over a subject’s life in a process called “permadroning.” In an experiment ahead of an eventual product launch, Wong implanted his now ten-year-old daughter Chalice with her own Destiny B.O.B at birth and dubbed the project “The Chalice Case Study.” The story that follows is as chaotic as it is complex.

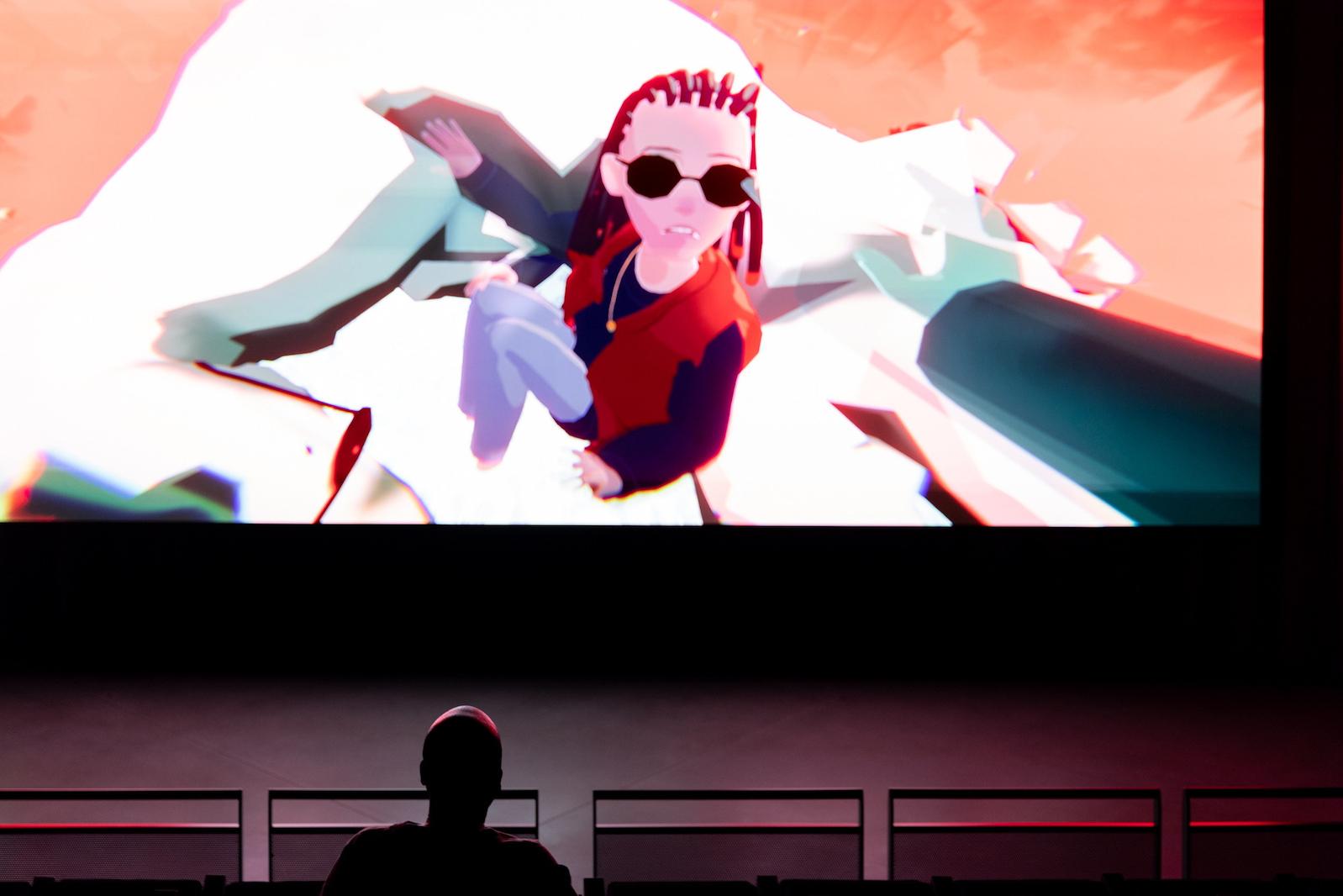

This commercialization of fate, as it were, depends on a construct called the Wavyverse, “a neural mental medium in which people can compose and share dream-like experiences directly with each other’s nervous systems.” The Wavyverse is traversed by wavecasting, a type of social media activity that allows a person to publicly stream “a curated combination of one's nervous system activities” (and just like today’s internet, wavecasting is exploited by self-promoting influencers). For those not into sharing, a “conflux” allows one to create a “private mental space” where “objects, scenarios, emotions, and physical sensations” can be conjured at will. Chalice bounces through the Wavyverse’s various hallucinogenic permutations in a mise-en-scène that’s inordinately complicated—which is why it’s advisable to peruse the show’s aforementioned website before visiting.