The Harlem Renaissance provided a space for some of the best Black cultural leaders to showcase their work. Following the ideals of the New Negro established by Locke in 1925, Archibald Motley (1891-1981) was a prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Based out of Chicago, Motley was the first Black artist to premiere his own solo exhibition in New York City. American art scholar Rachel Tolano maintains the assertion that Motley’s work resonated with a new generation of Black Americans who were fed up with the racist stereotypes of the past and sought to establish a new cultural identity. This new identity, arguably exhibited in Motley’s work, shows one of the flourishing Black societies in America’s largest cities, declaring these urban areas such as Chicago and Harlem to be epicenters of a vibrant Black culture.

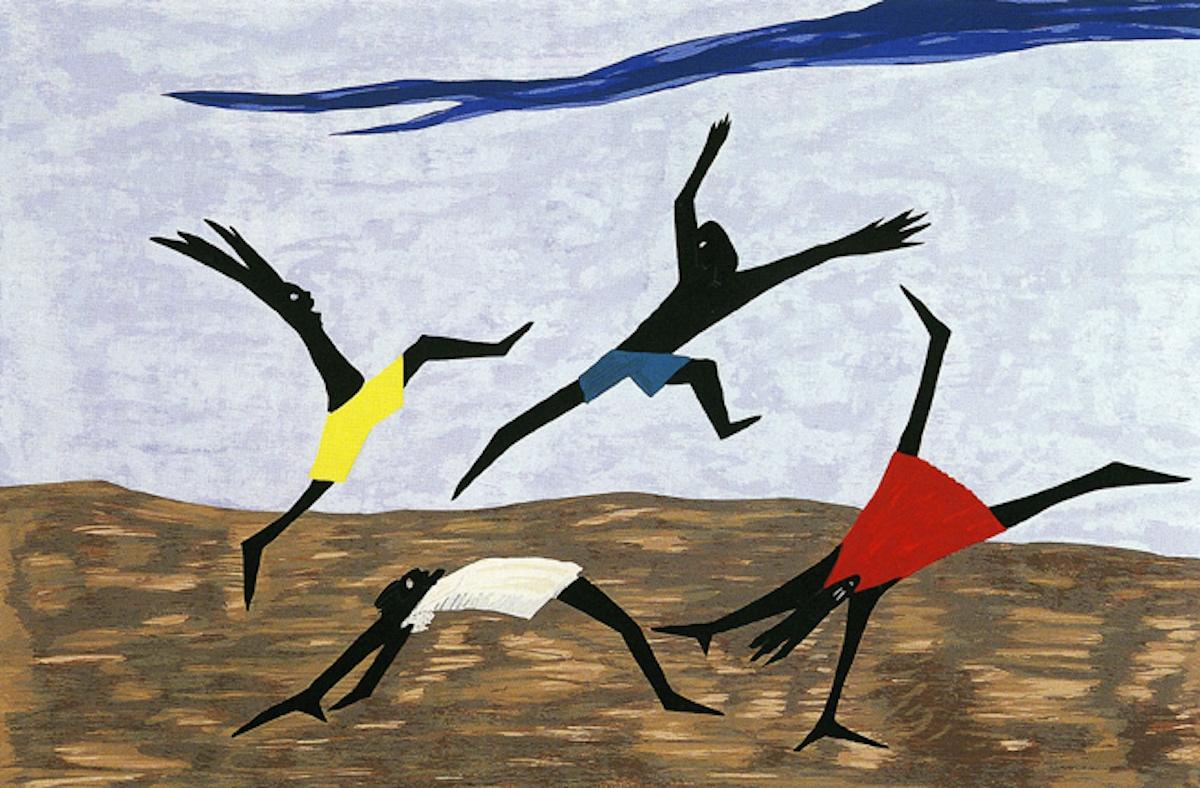

Jacob Lawrence, Harriet Tubman Series (Panel #4), 1940. Tempera on hardboard, unknown dimensions, Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia.

The Harlem Renaissance was an artistic and political movement that redefined Blackness in the United States as an act of liberation from post-antebellum discrimination and stereotypes, evidenced by Jim Crow laws and an abundance of blackface on-screen. Within this movement, Harlem in New York City served as the epicenter of Black philosophy, art, and music from the mid-1920s through the 1930s.

This movement aligned with the characteristics of the New Negro established by Alain Locke (1885-1954). Reliant on the ideals of economic independence from white America, the New Negro incorporated progressive politics, Black pride, and racial consciousness. Locke, who was the first Black Rhodes scholar as of 1907, arguably inspired the Harlem Renaissance to be the embodiment of the ideals of the New Negro, specifically in response to what Locke considered Old Negro stereotypes created by white society. The Old Negro identity excluded any self-identification from Black Americans, and cultural leaders such as Locke sought to shift the national narrative and showcase Black excellence. In this way, the Harlem Renaissance served as the vehicle for Black artists, philosophers, musicians, and writers to establish a new collective Black identity.

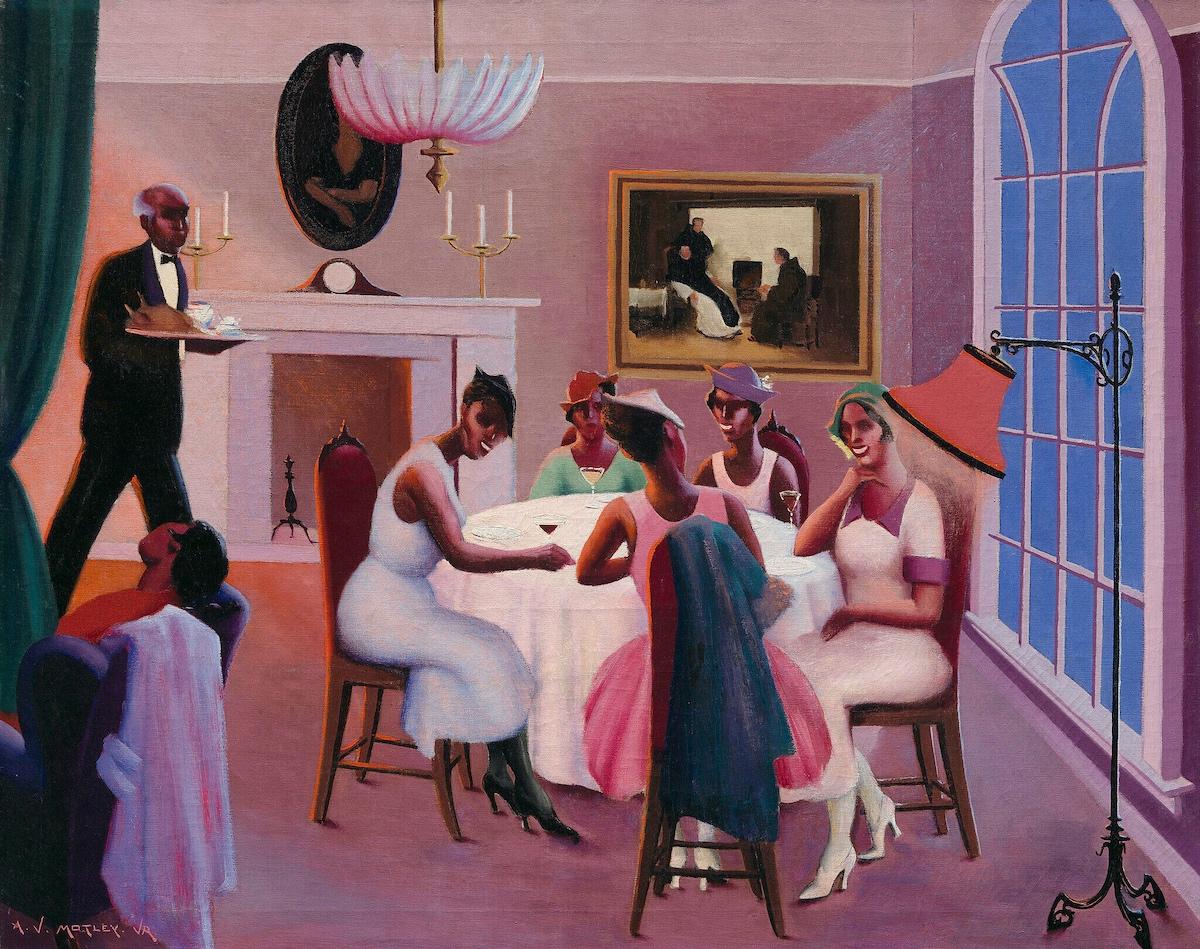

Archibald Motley, Cocktails, 1926. Oil on canvas, 32 x 40 in. (81.3 x 101.6 cm.), The John Axelrod Collection—Frank B. Bemis Fund, Charles H. Bayley Fund, and The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

Archibald Motley, Nightlife, 1943. Oil on canvas, 36 x 47.75 in. (91.4 x 121.3 cm.)

Motley’s works, such as Cocktails (1926) and Nightlife (1943), showcase the diversity within Black America, with a variance in skin tones across scenes, showing the Black middle-class being waited on by the Black working-class. Showcasing this socioeconomic structure within Black society is crucial to understanding the timeline of Motley’s works. Tolano argues that his earlier pieces like Cocktails conform to the social structure of the Old Negro, which is reliant upon the class structure imposed upon it by white colonization and slavery, as opposed to the vibrancy and freedom portrayed in Nightlife. This evolution in Motley’s works alone is arguably indicative of shifting perspectives on Black representation within American society.

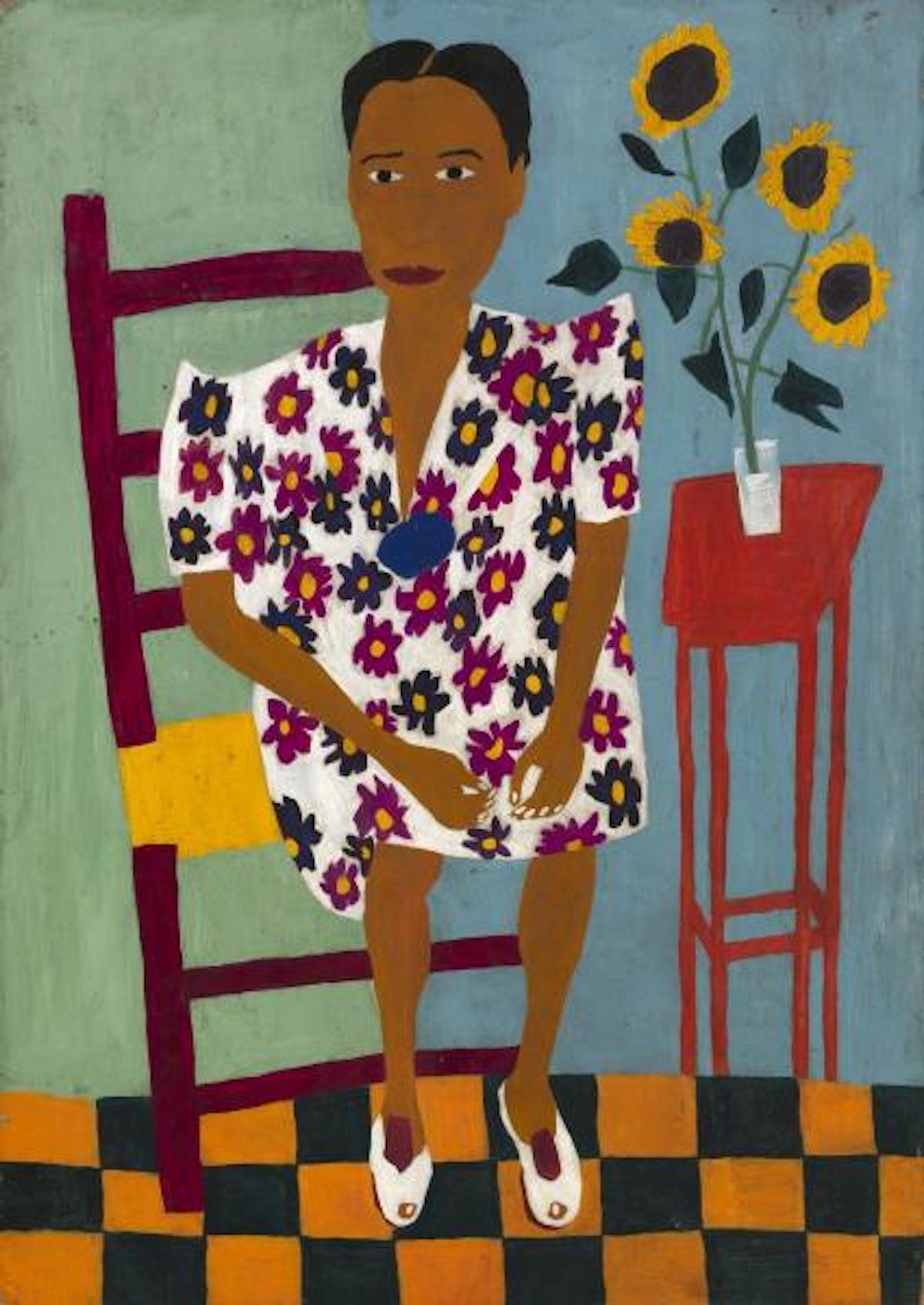

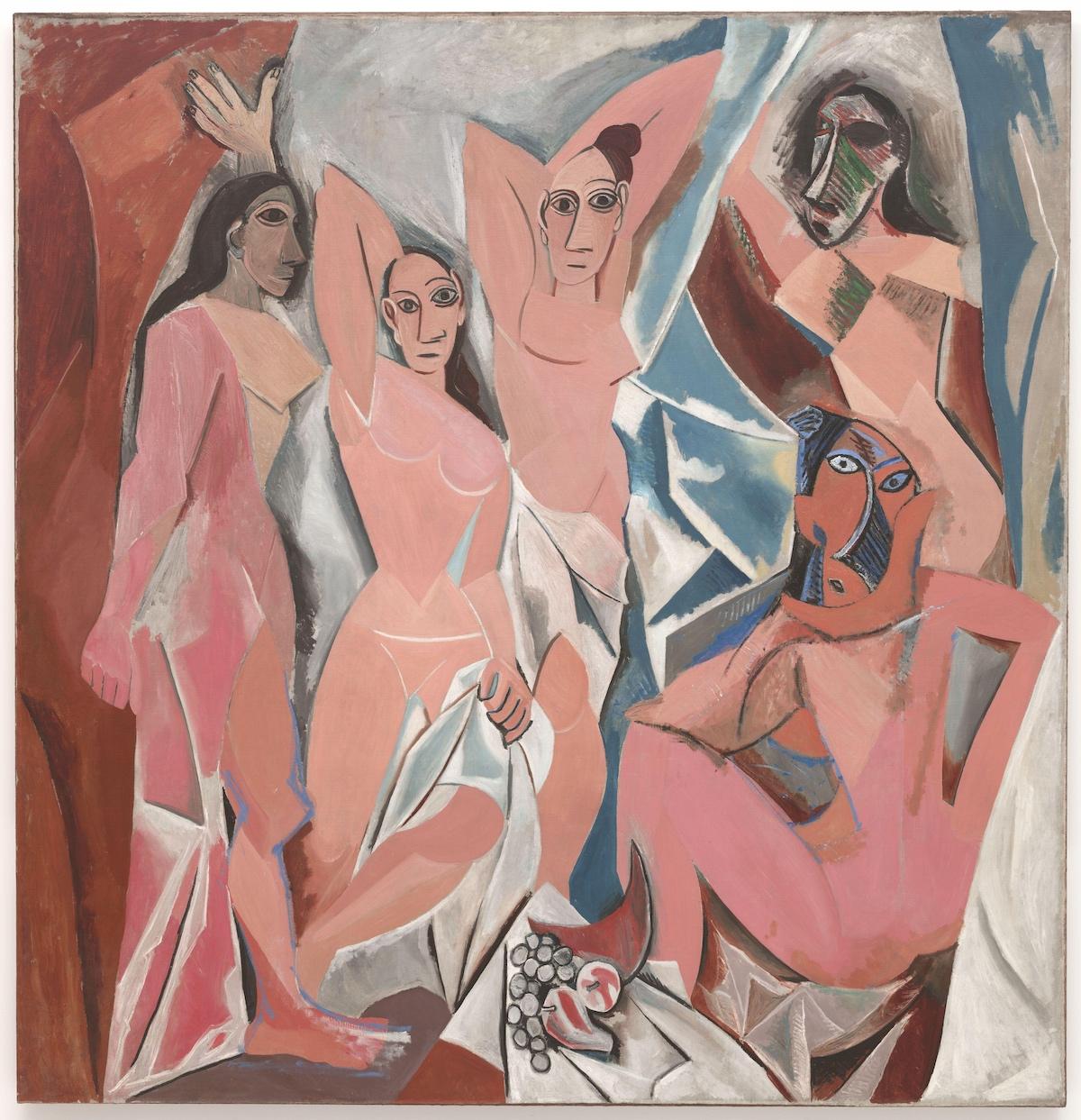

Continuing with the theme of shifting perspectives on Black identity and representations, the works of William H. Johnson (1901-1970) serve as a reclamation of the aesthetics of primitivism, a style of European Modern art popularized by artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). Primitivism sought to sensationalize and exoticize non-Western tribal life and art by deeming it “savage” and “naïve.”

Johnson’s work employs characteristics of primitivism like those used by Picasso for his Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) to characterize Black portraiture. In Johnson’s work, he reclaims the style, outside of a colonial lens. This reclamation is significant when considering the ideals of the Harlem Renaissance since it transforms the problematic roots of primitivism regarding African tribal art and revolutionizes it to become a distinctive style within the New Negro Movement.

The establishment of a new Black America within the Harlem Renaissance proves significant, past being a genre of Modern art in its influence on artists throughout the Civil Rights Movement and beyond into contemporaneity. The aesthetics of the New Negro Movement arguably continue to influence Black artists today, with its embrace of African aesthetics such as vibrant color, abstracted figures and lines, and geometric patterns. These characteristics have helped distinguish Black art in its own metaphorical lane, one rooted in pre-colonial history and rich tribal culture. In this way, the Harlem Renaissance not only empowered a new Black identity one hundred years ago but continues to push the boundaries of what exactly Black art is – or should be.

“They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.” – excerpt from Langston Hughes, "I, Too" from The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. Copyright © 2002 by Langston Hughes.