Lasansky’s parents were Jewish immigrants from Romania who had moved to Argentina to escape pogroms before he was born in 1914. He moved to the United States in 1943 for the first of five Guggenheim Fellowships, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen and starting the first Master of Fine Arts program for printmaking at the University of Iowa.

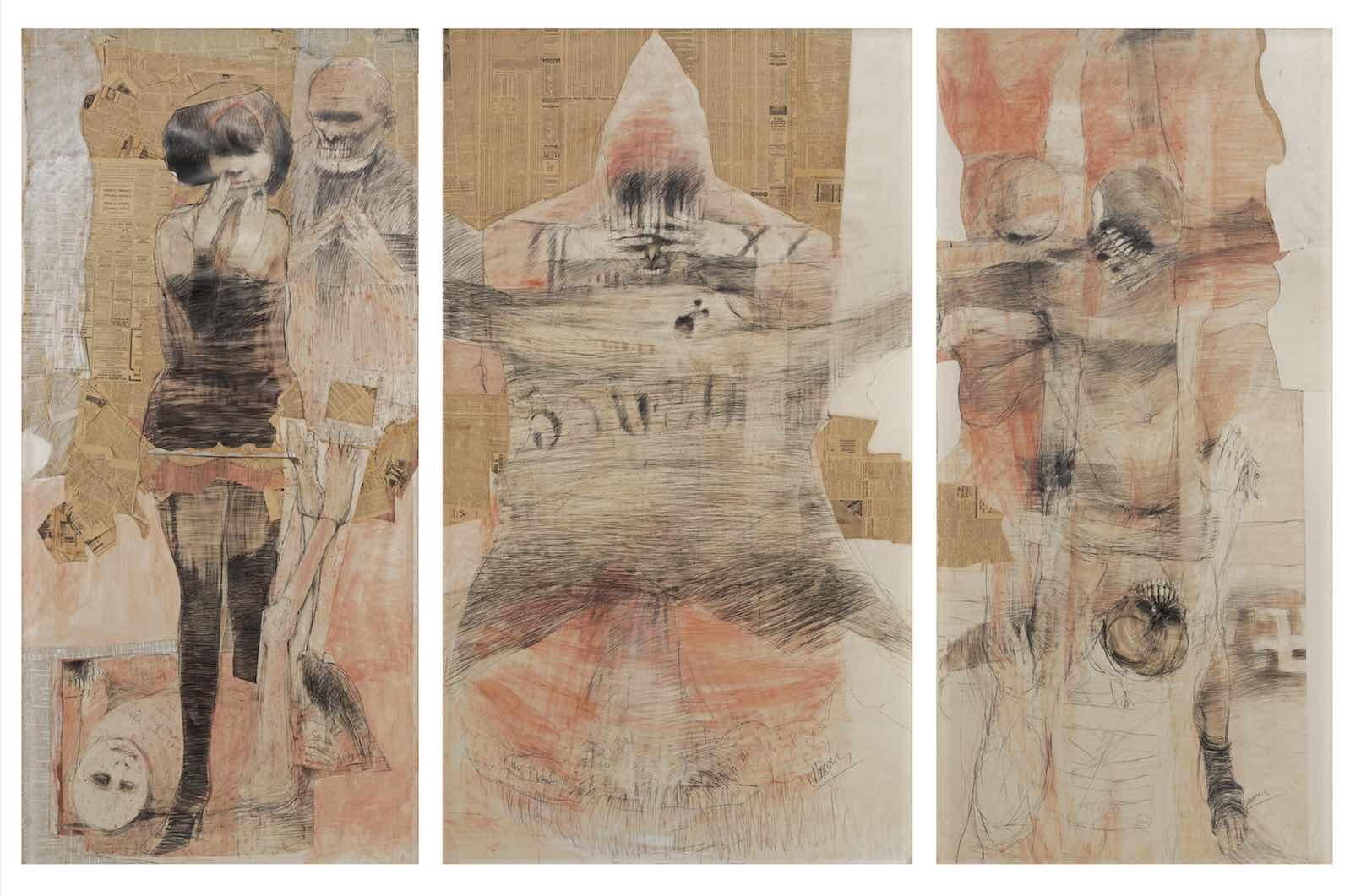

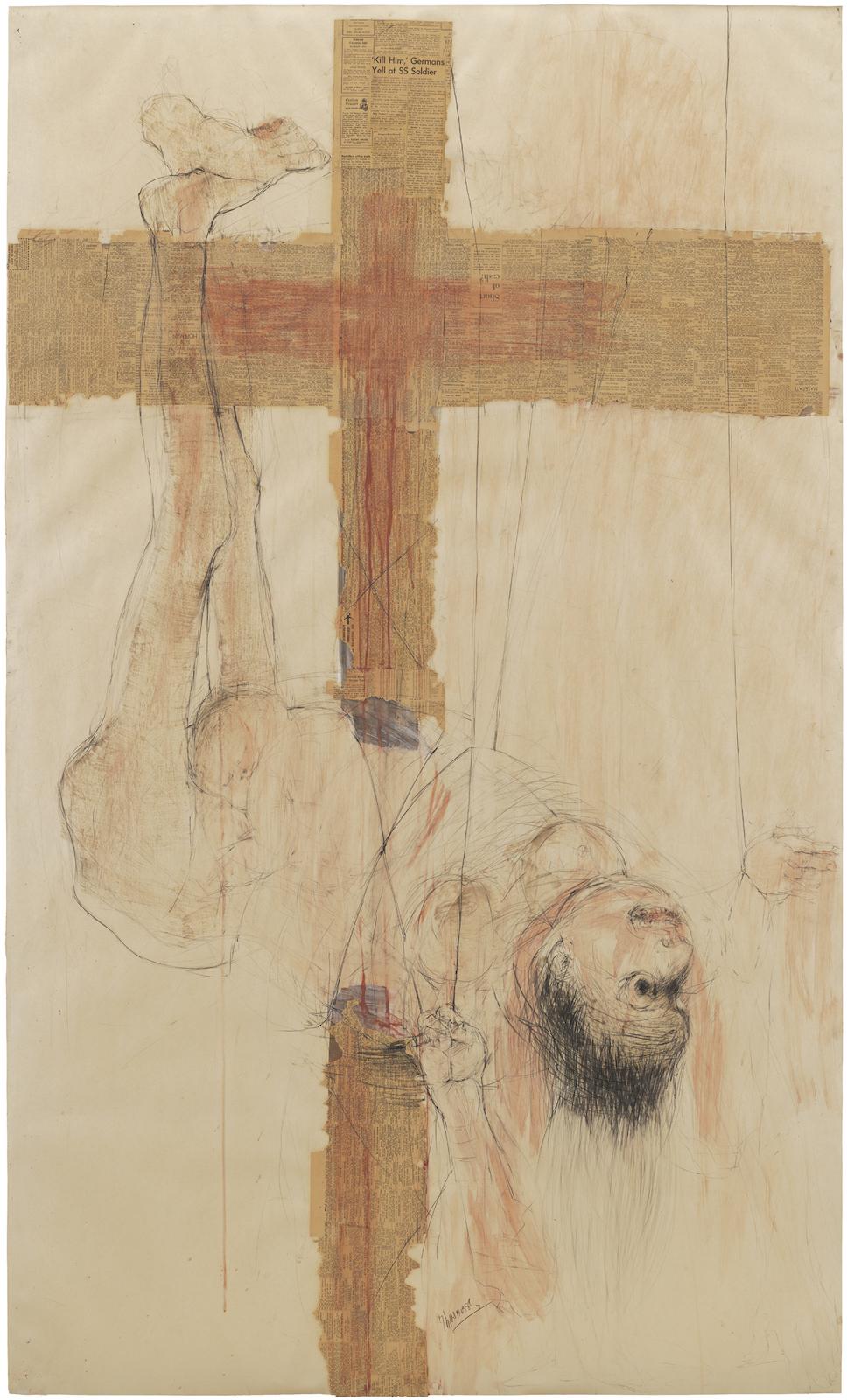

Lasansky was called the “nation’s most influential printmaker” by Time Magazine in 1966, and explored abstract expressionism early in his career before turning to portraiture, according to Rachel McGarry, associate curator at Mia.

Lasanky began creating these artworks in the wake of the internationally televised 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, an SS officer who had been a major organizer of the Holocaust. The trial included the testimony of ninety survivors of concentration camps who, in their stories, gave faces and names to the atrocities that occurred in the Nazi’s “Final Solution to the Jewish Problem.”