Instagram post from Chidiebere Ibe's account @ebereillustrate captioned, "Our goal is to spur interest for neurosurgery in the African Student."

Nigerian medical student and illustrator Chidiebere Ibe has recently gone viral. Or rather, his medical illustrations have—for the simple reason that they represent the Black community, a stunning rarity in the medical world to this day.

Currently enrolled in Ukraine’s Kyiv Medical University, Ibe has created work that's thankfully sparking important conversations about the lack of racial diversity across the Western medical world in particular. The illustrations have additionally prompted this author to reflect on the history of Black representation in scientific texts and how it has impacted the treatment and perception of patients of color through the centuries.

Devastating consequences within the context of science and medicine are unfortunately nothing new to members of the Black population in colonial spaces. This is particularly evident in the Western art history of medical illustrations that feature Black people. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these racist artworks are largely rooted in the Age of Enlightenment and the transatlantic slave trade.

Although the Enlightenment era is largely characterized by a sweeping fascination with art, philosophy, and science, as well as a new understanding of and respect for the rights of man, it also gave birth to a brutal system of racial classification and scientific racism—something we still feel the impacts of to this day.

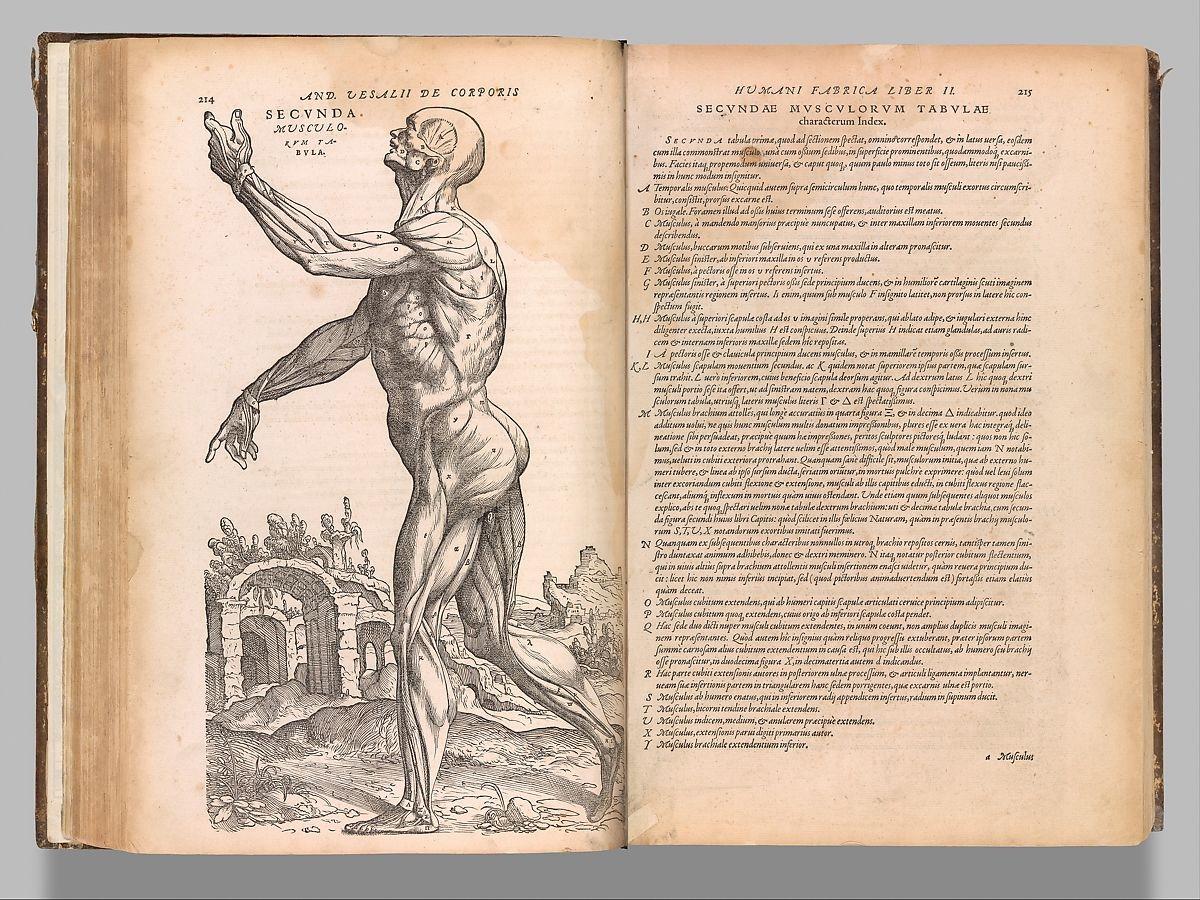

John of Calcar, illustration for De humani corporis fabrica (Of the Structure of the Human Body) by Andreas Vesalius, 1555. Woodcut.

These two aspects of the Enlightenment can be difficult to reconcile—how can a period steeped in equality and education have led to such devastating, groundless racial theory?

The author of The Funding of Scientific Racism William H. Tucker explains it well: “as Enlightenment rationalism replaced faith and superstition as the source of authority, the pronouncements of science became the preferred method for reconciling the difference between principle and practice. In societies in which there has been systematic discrimination against specific racial groups, inevitably it has been accompanied by attempts to justify such policies on scientific grounds.”

Many of these attempts to justify racism used taxonomy, the science of classification, to justify their stances. Though its development was driven by naturalists, it was also adopted by those who wished to establish and elaborate on theories of racial difference. Many of these adoptees argued that differences in skin color, hair texture, and so on actually indicated a difference in species. Polygenists, for example, believed that different racial groups evolved from entirely different ancestral groups.

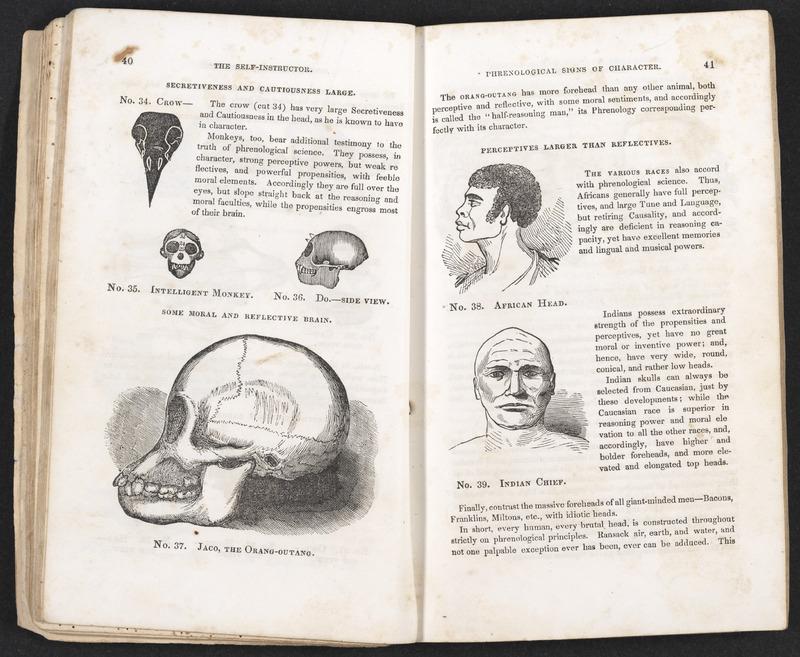

O. S. Fowler (1809-1887) and L. N. Fowler, The Illustrated Self-instructor in Phrenology and Physiology, 1850.

Though physiognomy—a pseudoscience that sought to prove a link between appearance and personality—existed long before the Enlightenment, it remerged in full force during this period and was often levied with taxonomy to justify those aforementioned theories of racial difference. The text above, for example, argues that Black features indicate an innate “subservience.” Such claims were often used to justify chattel slavery.

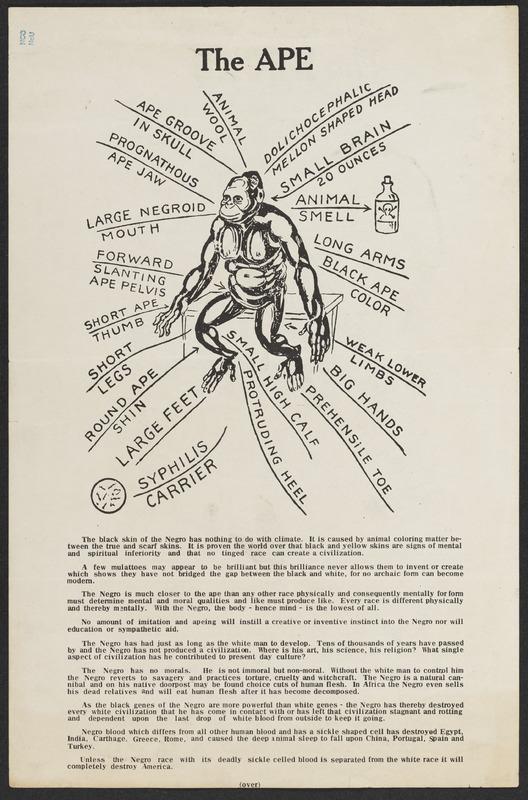

A anti-civil rights broadside entitled The Negro (Africanus)/The Ape, c. 1960s. Created in Hillsboro, North Carolina.

Even after these practices became widely denounced by the scientific world, the language that emerged alongside them continued to appear in Jim Crow era propaganda and still appear to this day in disgusting memes and racial epithets.

Though unacceptable, it is also somewhat unsurprising that the dehumanizing imagery populating eighteenth and nineteenth-century texts was followed up by a complete absence of representation.

As the following statistics demonstrate, this lack of representation goes far beyond medical illustrations.

According to data gathered by the Association of American Medical Colleges in 2018, only 5% of active physicians are Black while more than 56% are white. As 2019 US Census data shows, this gap is substantially larger than the gap between the overall population percentages of Black and white individuals.

Black people are even less represented in the world of medical trials—a statistic that has devastating consequences. As stated by Ada Stewart, M.D., in an article published by the American Academy of Family Physicians, Black patients “have the highest death rate and shortest survival rate of any group in the United States for most cancers.”

Still detail from Ibe's video, GoFundMe Campaign: Chidi to Kyiv.

It is clear that a problematic lack of representation exists in the medical world and, more importantly, that it can have devastating consequences.

In light of all of this, Chidiebere Ide’s illustrations, and his pursuit of a medical degree in a Western country, offer more than equal representation. By depicting Black individuals as fully human—as just as capable of contracting illness, feeling pain, and being healed as their white counterparts—Ide is slowly but surely contributing to a correction of the past that will hopefully have a positive impact on the future.