Elaine, the Lady of Shalott, whose unrequited love for Sir Lancelot drove her to death, and Shakespeare’s Ophelia became the embodiment of mental frailty and post-mortem catharsis. John William Waterhouse’s 1888 depiction of the Lady of Shalott shows her as wan and helplessly insane as she’s floating in her boat shortly before meeting her demise.

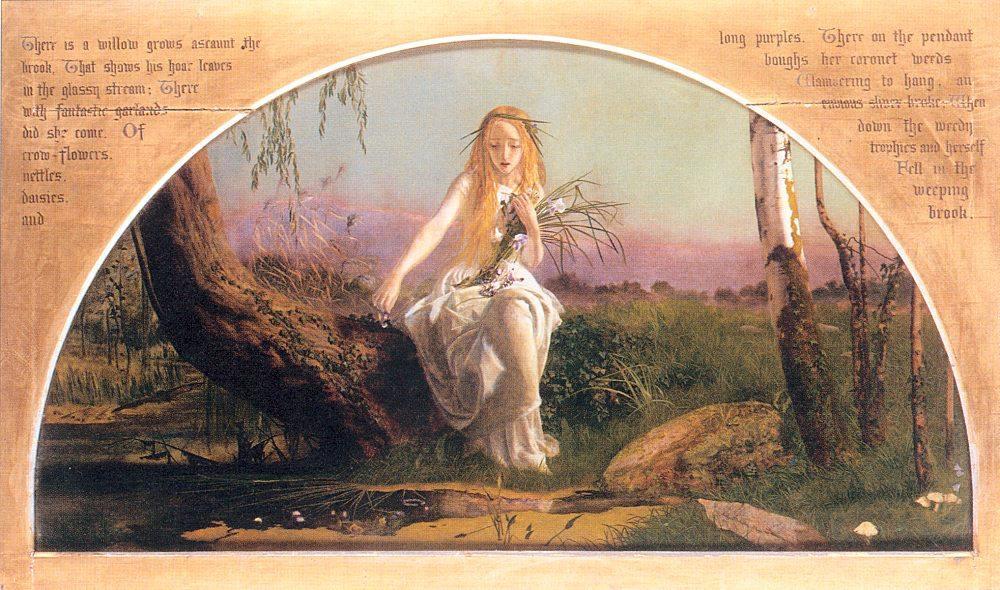

Ophelia, by contrast, is labeled by Dijkstra, as “the nineteenth century’s all-time favorite example of the love-crazed and self-sacrificial woman.” While she was quite a minor character in Hamlet, she became the ultimate muse of late-nineteenth-century painters. John Everett Millais’ version might be the best-known one, with Ophelia floating in a body of water, but there are multiple other interpretations of her fragility: in Arthur Hughes’s first version of the character (1852) we find her at the edge of the brook where she would ultimately drown, with an anguished expression, her face childlike, while her body appears emaciated. Adolphe Dagnan-Bouveret’s version (1900) offers a more dramatized representation, with a confused Ophelia holding a bunch of flowers in her hand in a dark, forest-like setting.