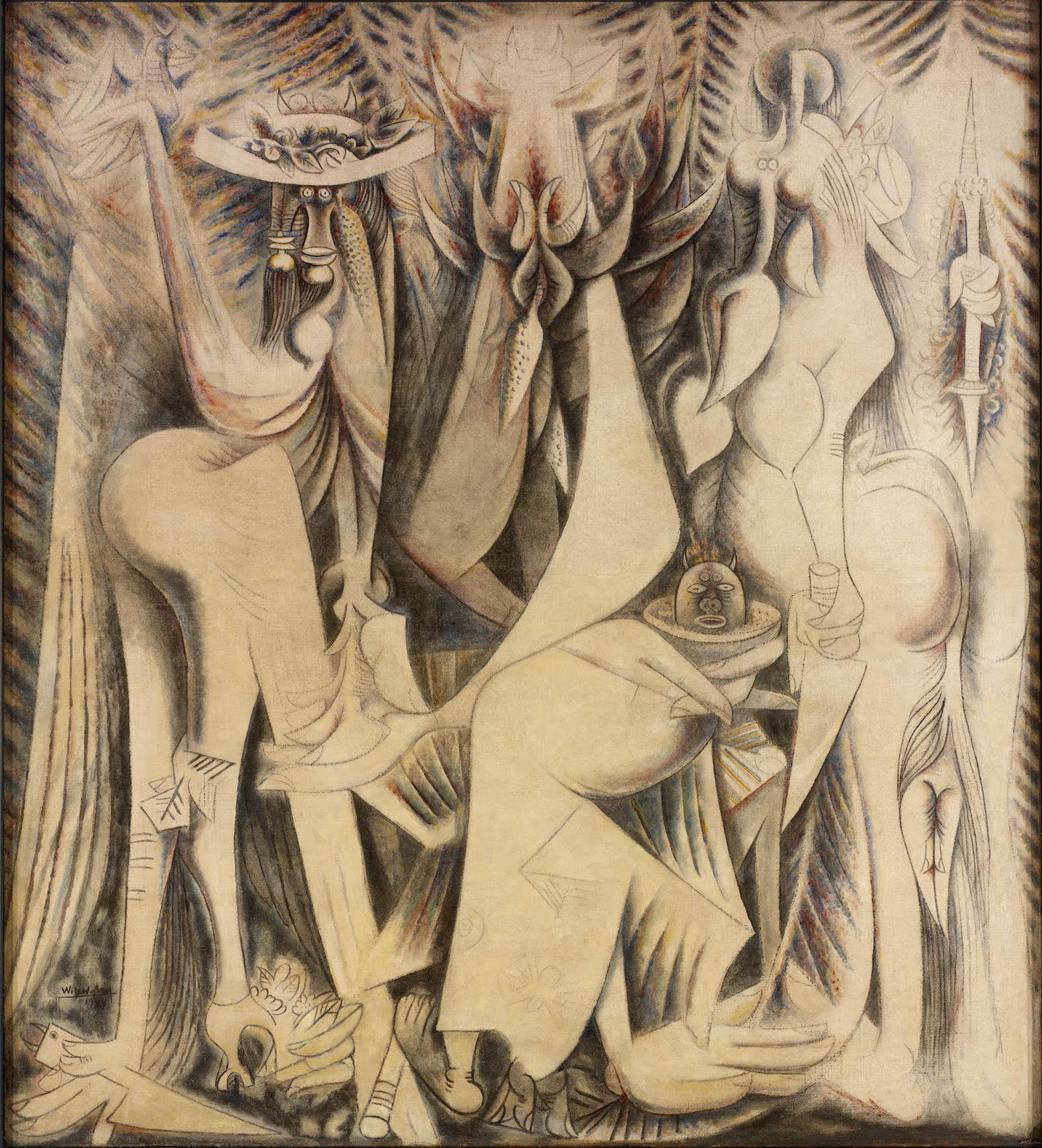

In an October 1924 manifesto, Breton anointed himself the official arbiter and enforcer of Surrealism, while engaging in a sort of battle over IP with Yvan Goll, a rival for control of the Surrealist brand who’d issued a similar decree two weeks earlier. Breton’s writing barely mentioned art, yet he would win the allegiance of painters and sculptors, consigning Goll to the dust heap of history. Breton became Surrealism’s Johnny Appleseed—the disseminator (and inspiration for other disseminators) of its tenets around the world.

The exhibit posits that Surrealism grew more subversive and politically engaged as it radiated from its point of origin, but it was plenty radical where it began. More than just heaving the subconscious into view, Surrealism, like much of the early twentieth-century avant-garde, was a reaction to World War I, when Europe’s old order destroyed itself in the trenches, taking with it the traditional ways of seeing. Civilization couldn’t compete with the Boschian hellscape of the Western Front, so the Surrealists dug among its ruins for an alternative reality.