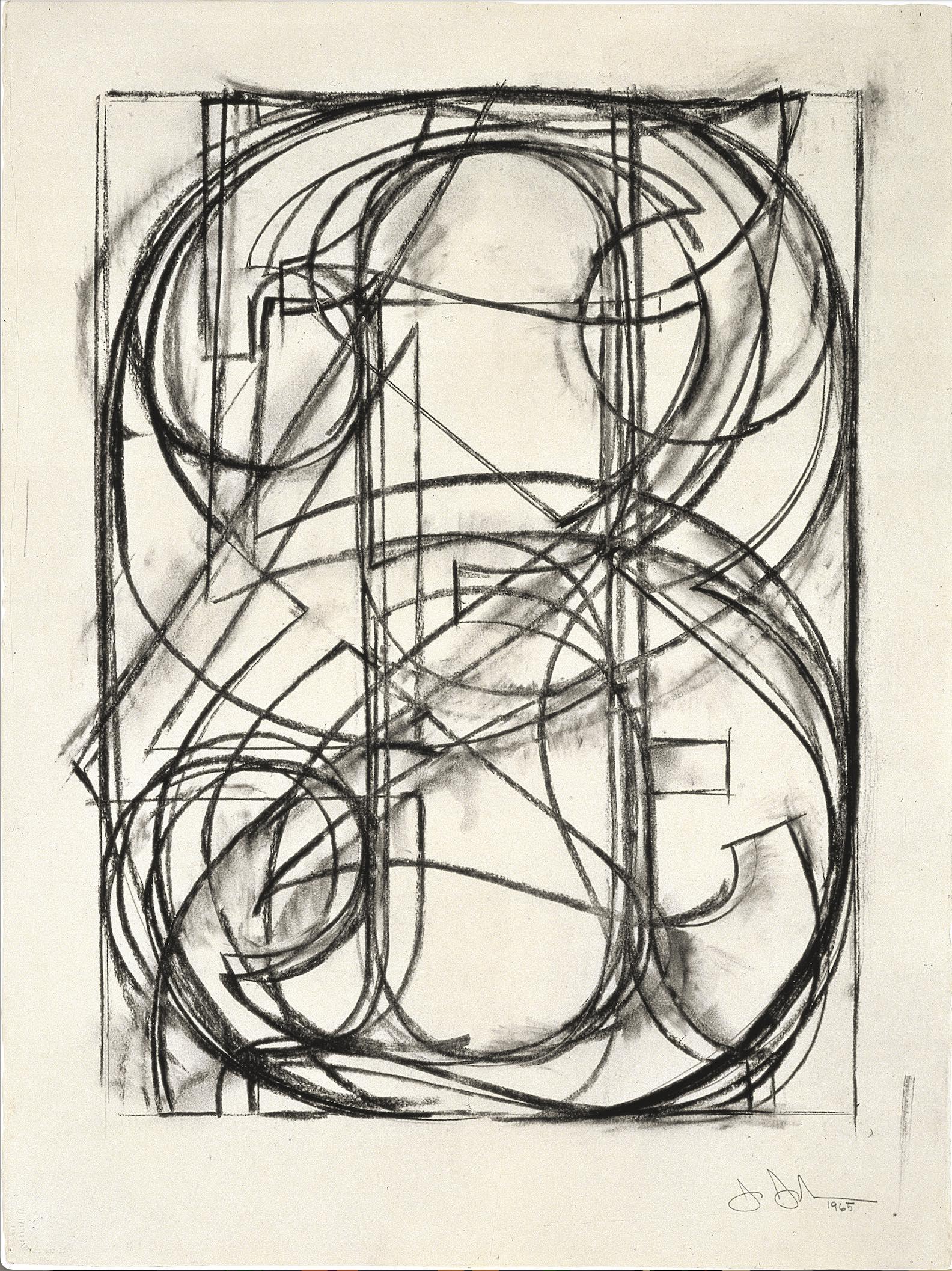

This wasn’t a sure thing back then. NYC’s art scene was still dominated by Abstract Expressionism, the movement that had brought American artists to the dance of art-historical relevance. By reviving Marcel Duchamp’s readymade aesthetic through painting (a medium Duchamp himself disparaged), Johns coolly dissected the broad, gestural psychodrama of artists such as Pollock and De Kooning. He countered their performative sturm und drang with subjects that obdurately concealed as much as they revealed.

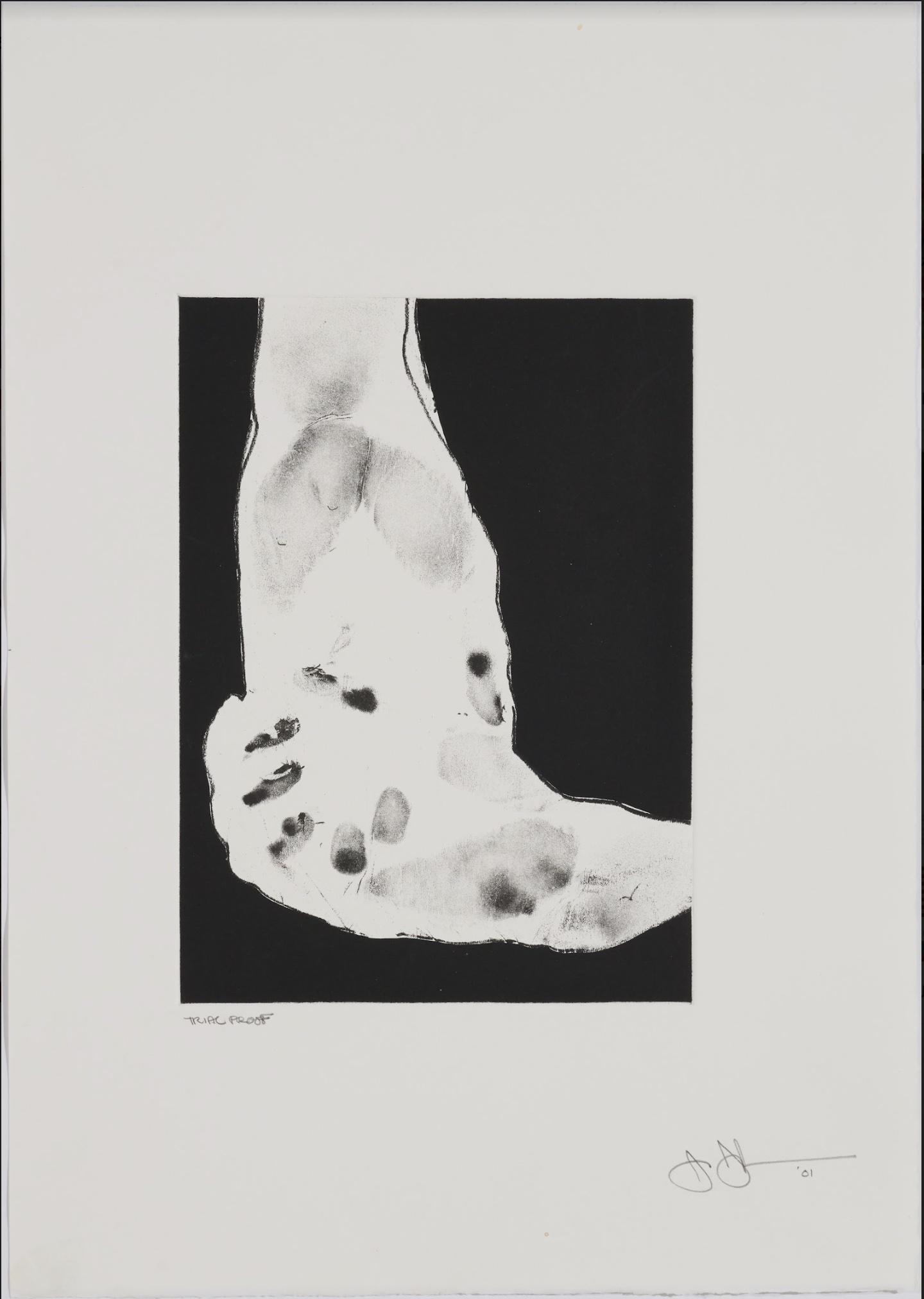

Johns’ breakthrough Flag from 1954 (which came to him in a dream), was a particularly provocative riposte to AbEx. Obvious on its face, it is a rendering of Old Glory on a canvas conforming to its shape. But is it an image of a thing or the thing itself? Both and neither: A mute presence, yet also an ironic commentary on America’s superpower status by a gay Southerner obliged to deal with the macho pretentiousness around him. Key to its effect is Johns’ use of encaustic: A mix of pigment and wax, which he applied in short strokes over skeins of collaged newspapers; tantalizingly visible under translucent daubs of color, they’re impossible to read.