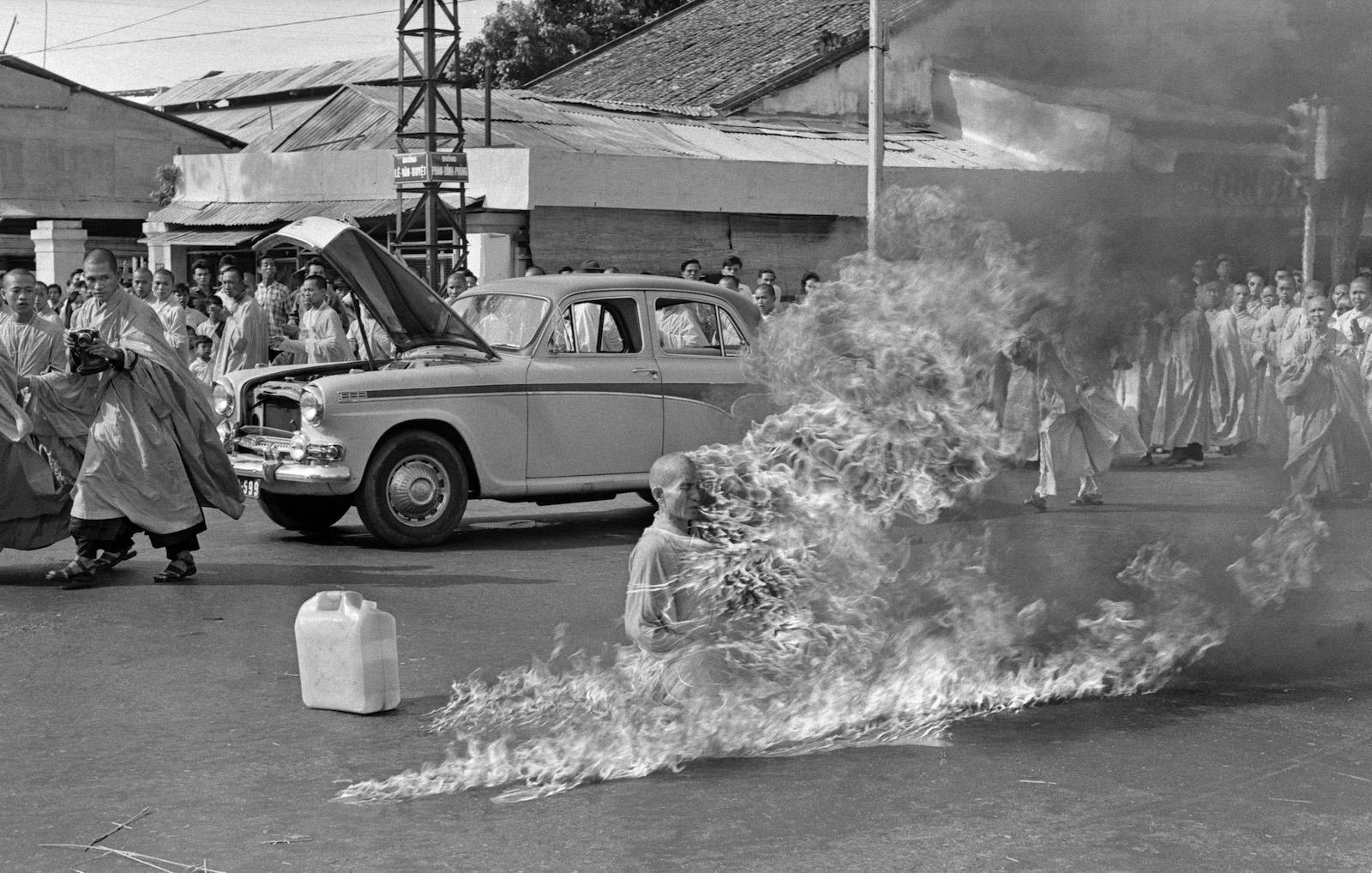

The impact of this image was immediate: the Kennedy administration reassessed its policy on Vietnam by increasing the number of troops in the country. The rest, as we say, is history.

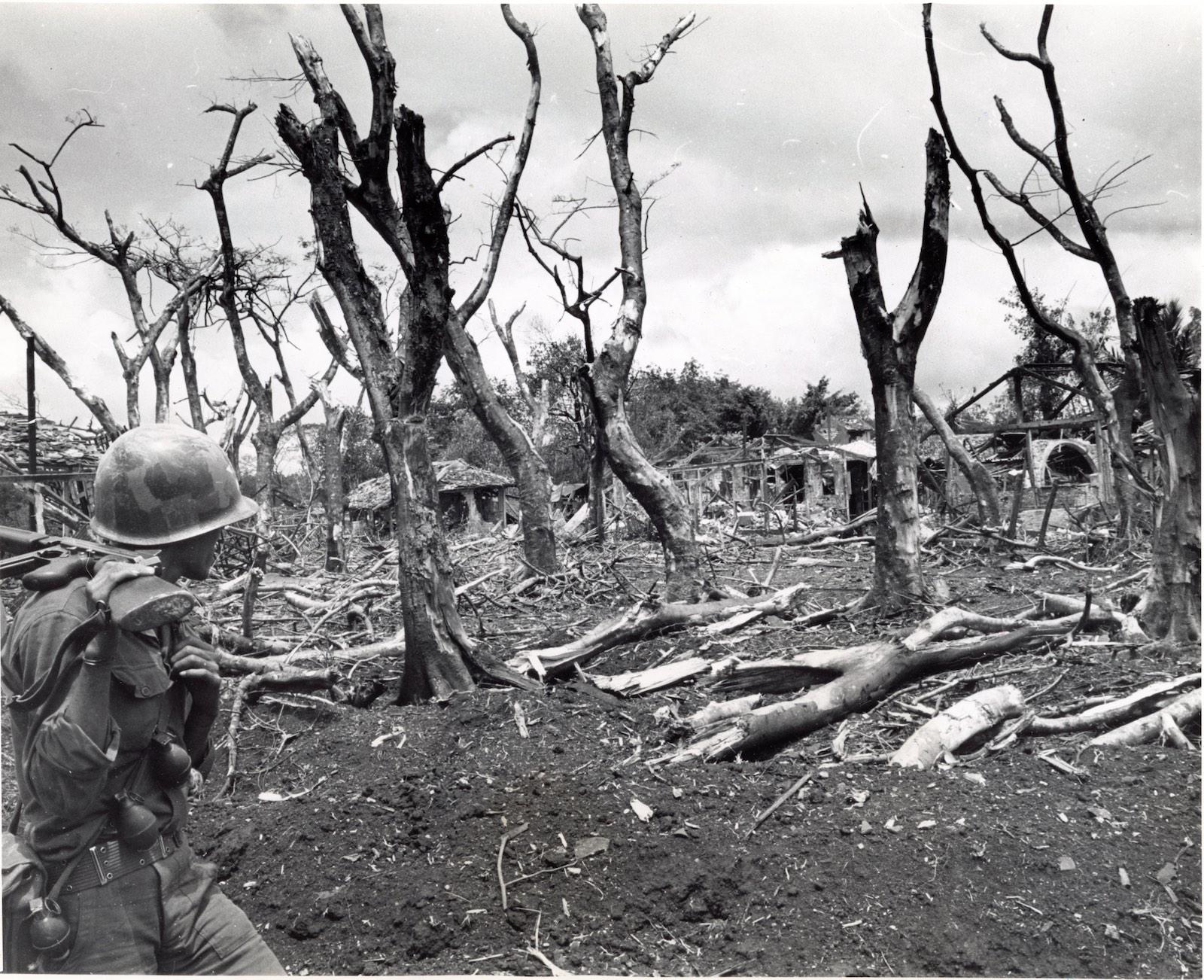

In The Camera at War, Jorge Lewinski noted that “So far as the photographic coverage is concerned, there never was, and probably never will be, another war like Vietnam.” Lewinski was not only referring to the amount of photographers and correspondents on the ground, but more specifically, to their unprecedented—and never allowed again—freedom.