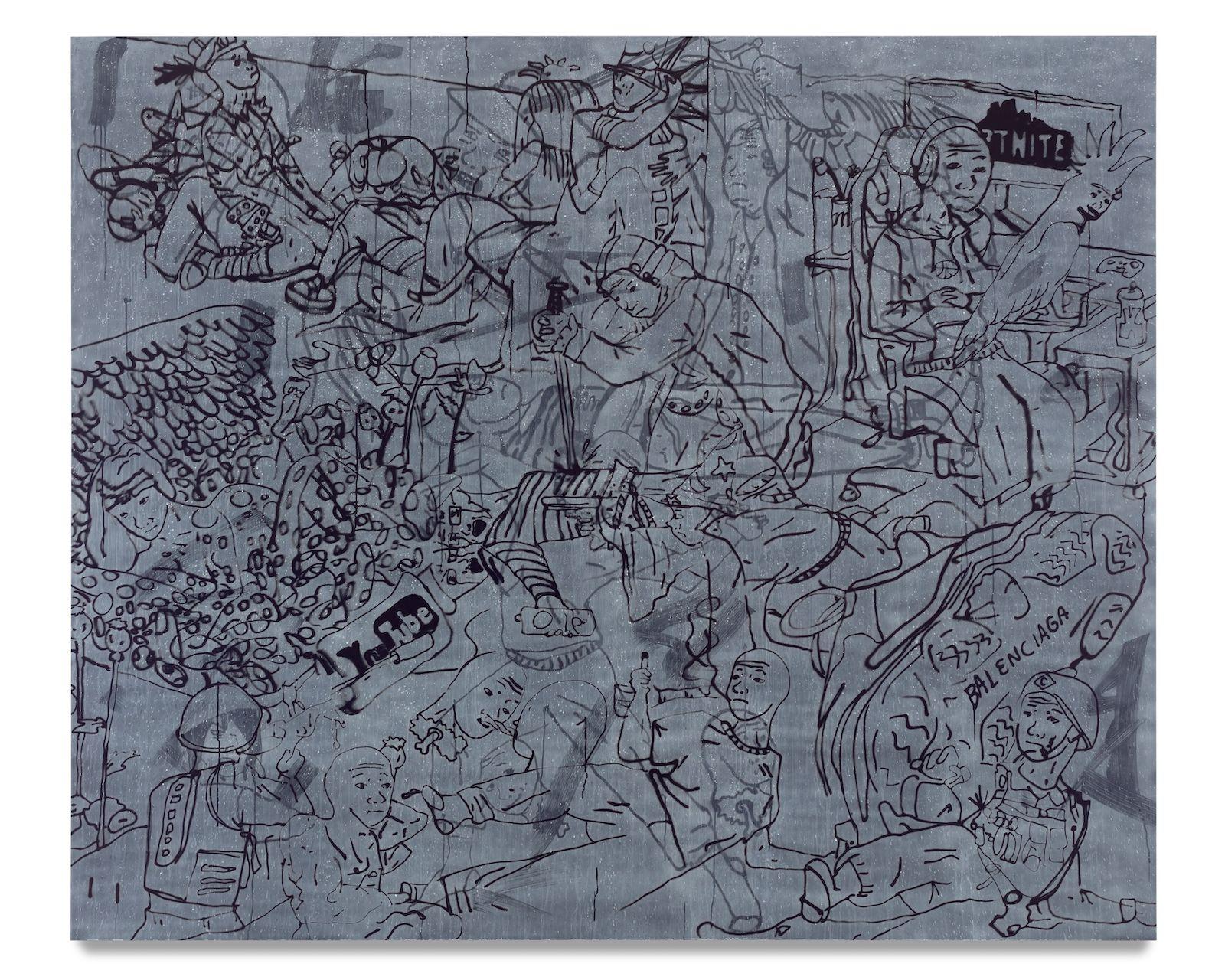

More effective is Wojak Battle Scene (2021), which portrays the most disorganized army I’ve ever seen. Against a green backdrop, soldiers fight individual battles that never seem to coalesce. One soldier stabs a sword into a man with a striped shirt below him who looks like he’s sleeping. In another corner, a man with headphones plays Fortnite, a battle-focused video game. Nearby, a soldier points a gun at nothing. YouTube and Balenciaga logos are interspersed too. Even in wartime, we can’t resist the urge to place advertisements, or to think about a video we just watched on YouTube.

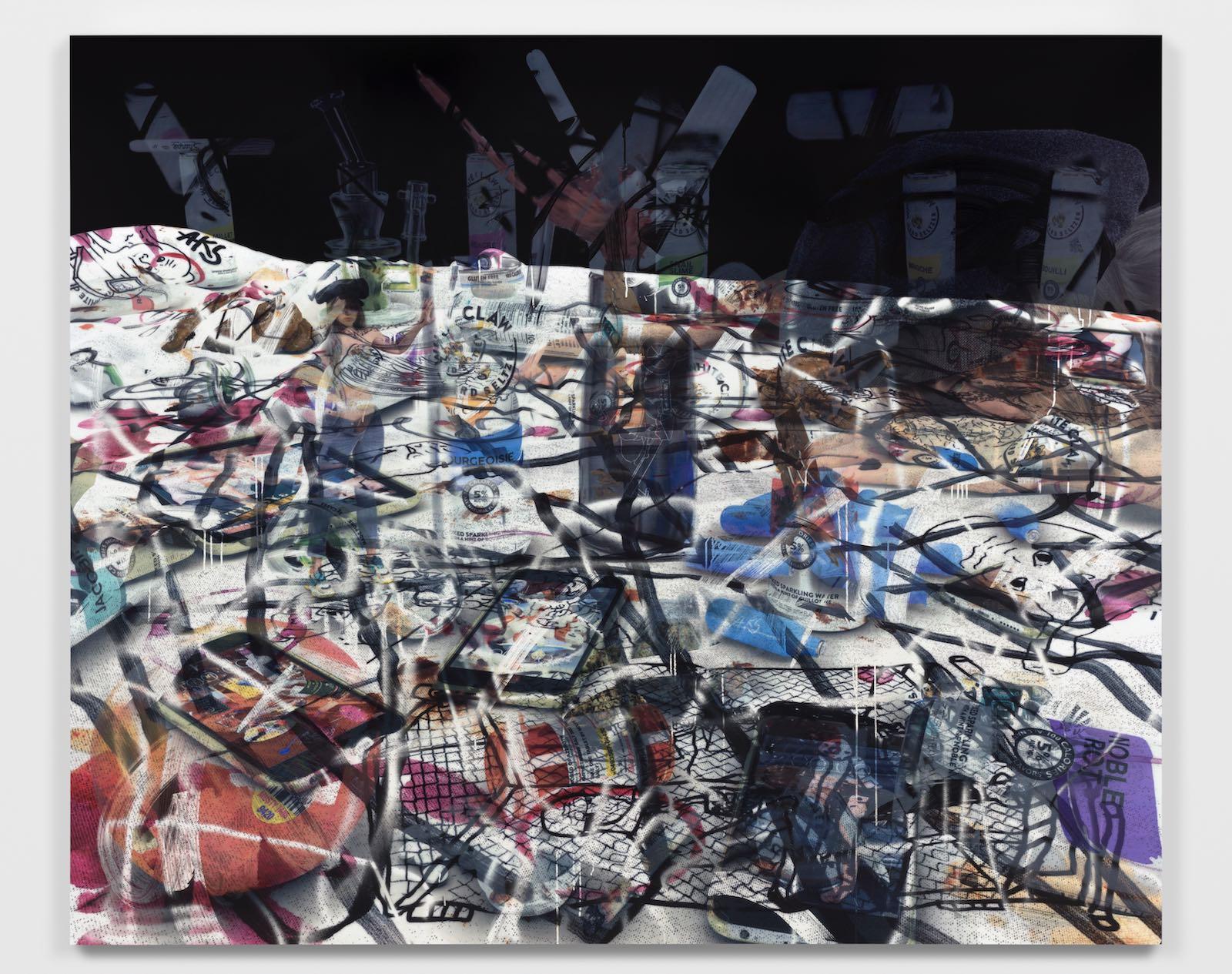

China Chalet (2021) connects to the internet but also introduces another theme that runs through the show: the promise and peril of intoxication. It depicts the detritus of a night out at the now-shuttered restaurant and club. There are bottles of pills, poppers, and other drugs strewn across white tablecloths, labels from White Claw hard seltzers, and lots and lots of iPhones, because even when we’re not confined to the internet, we’re still performing for it. Layered over the display are flashes of red and blue paint, and lines of acrylic rubber, making deciphering what’s underneath like trying to piece together the moments of a half-remembered night. It made me miss them.