Ubisoft has long stated that one of their greatest strengths in creating the worlds of Assassin’s Creed has been the close collaborations fostered between their artists, programmers, and game developers with historians, archaeologists and other experts across different fields.

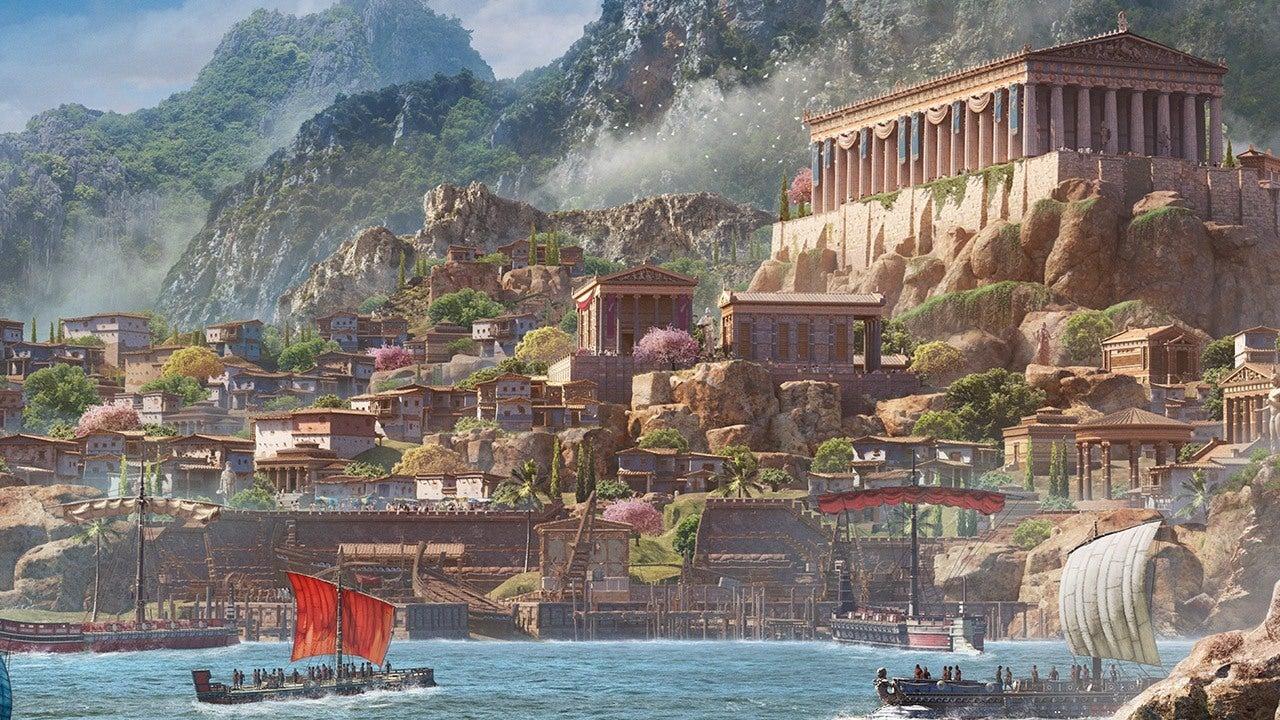

The results have been nothing short of impressive, culminating in the creation of the stunning landscapes and incredibly detailed cities of various ancient locales.

Two of the most recent games in particular, Assassin’s Creed: Origins and Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, have been especially successful in their recreations. The dazzling reconstructions of Pericles’ Athens in Greece (Odyssey) and Cleopatra’s Alexandria in Egypt (Origins) are true testaments to the power of the collaborations between scholars and game developers.

The precision of detail at every game level showcases just how much care and thought goes into creating these worlds. From the characters’ clothing, to the furnishings in their houses, and even scattered objects in city streets, no detail of what we know about the ancient world was overlooked in the creation of these games.