Paul Laster: When did you initially become interested in art and how did you express that fascination?

Robert Nava: I began by drawing and scribbling abstractly as all kids do, but I consciously started drawing cartoons and cereal box characters around seven or eight and continued an interest in art through my school years. Art class was definitely my favorite subject.

PL: What did you learn during your undergrad art studies at Indiana University Northwest that helped prepare you for grad school at Yale?

RN: I learned how to draw and paint representationally—from still life to live model—in a very traditional way, but in my final year I was told, ‘now that you are an artist there are no more assignments and you can do whatever you want.’ Even though the school was in Indiana, we were close to Chicago and my professors would tap their friends at the Art Institute of Chicago and Northwestern University to be visiting artists. It was wonderful to be exposed to many different avenues of thought, but the challenges at Yale were far greater.

PL: Which instructors at Yale made an impact on the art that you’re currently making and what was it about them or their work that appealed to you then and still does now?

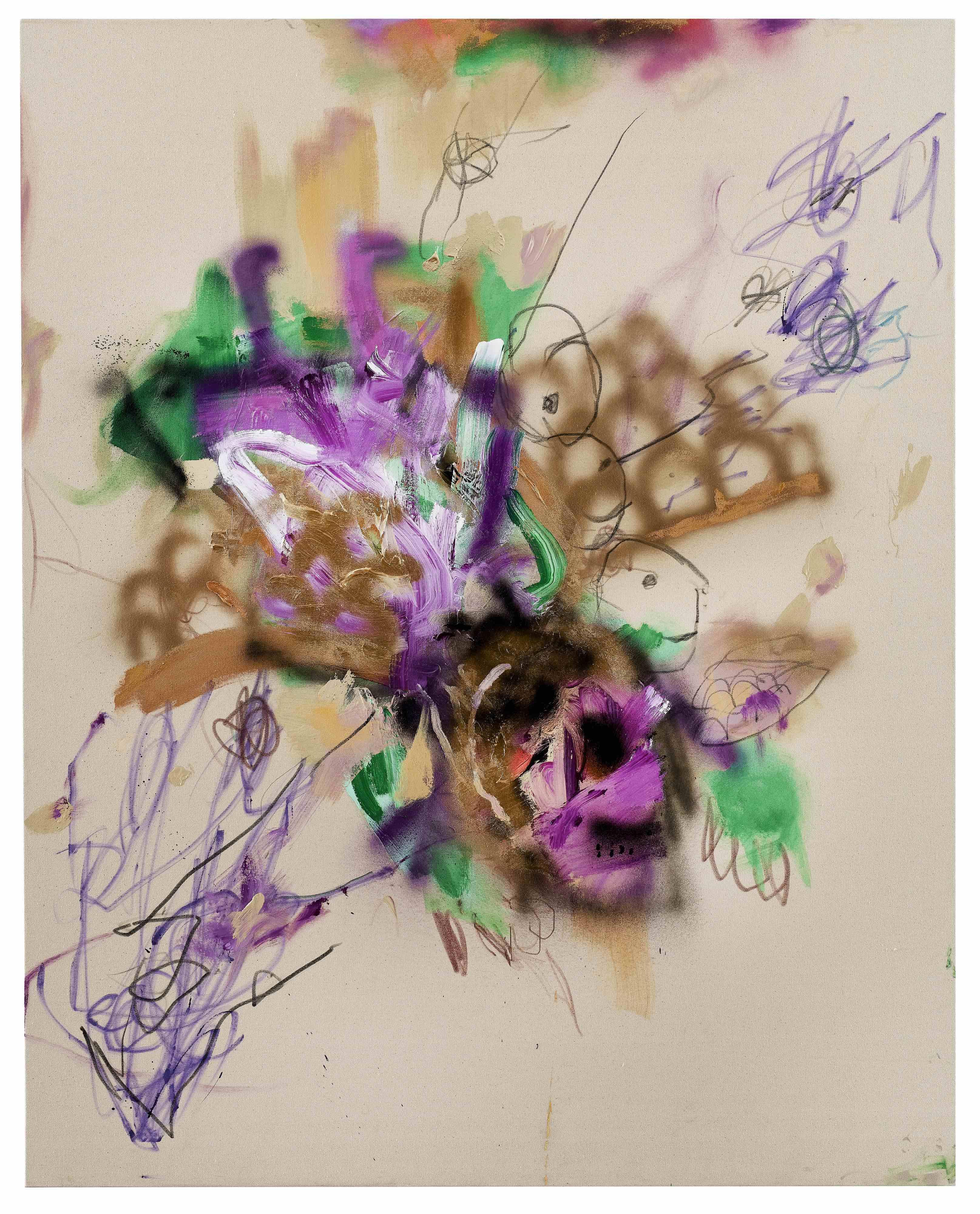

RN: That’s a tough one because there were so many good teachers and visiting artists there, and I liked a lot of them—even when they were pushing hard, because I realized that it was for my benefit. I really connected with Peter Halley, Huma Bhabha, and Carroll Dunham. They were the standouts, but there were a lot of others who made me think. As far as sticking with me, Huma Bhabha is still one of my favorite artists. I like how she combines the ancient with the sci-fi and the way she uses offbeat materials. She looks the gods and monsters directly in the face and then cranks the volume up full blast.

PL: How long did it take after leaving college to unlearn what you had been taught and discover your own distinctive way of working?

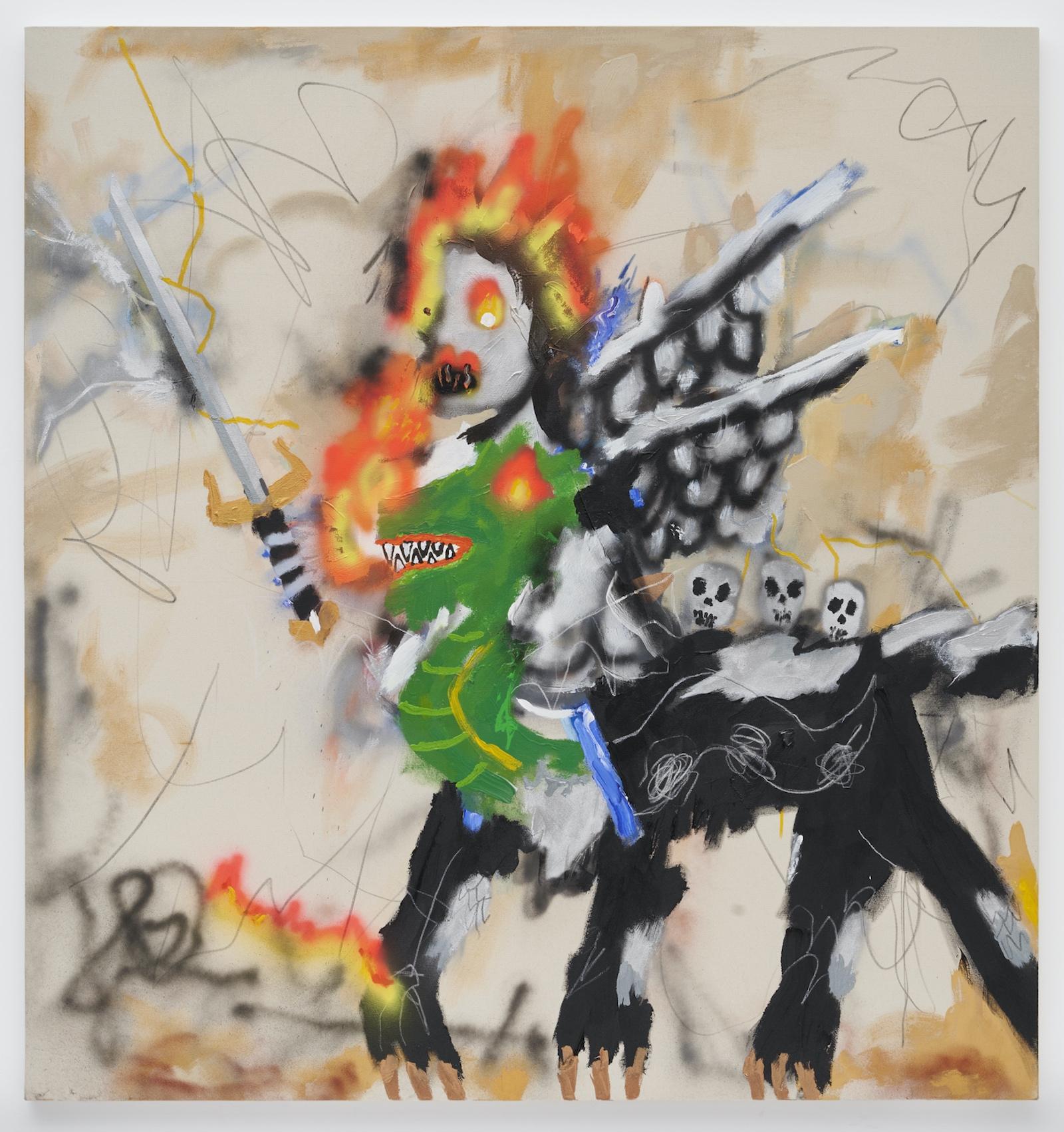

RN: It came pretty quickly because I wanted to get away from the conventional way of making art. I rented a raw studio in Brooklyn, where I was continuously experimenting and fumbling around. It wasn’t that I wanted to do things wrongly, but I was open to error. I relied on my intuition and quickly gained confidence. I made a series of truck paintings and then started passionately drawing and painting mythological beings and beasts.

PL: What was your first big break and how did it affect your confidence going forward?

RN: It came when Roberto Paradise—a gallery based in San Juan, Puerto Rico—exhibited my paintings at Expo Chicago in 2017. It was the first place where my new style of painting was physically shown. The gallery presented a painting of an alligator eating a man, Crunch, and another big canvas of a fiery winged horse, Flamethrower Pegasus, and I immediately knew that these paintings were unlike anything else at the fair. It was a big deal for me, especially since it happened so close to home.

PL: Did struggling in an urban environment help shape your raw style of figuration?

RN: Yes, and it started in my studio building, which was full of graffiti. I’m not sure if I fully understand how inspiration works, but subconsciously seeing all of the marks on the walls and seeing the aggressive nature of the city while working as a truck driver—as fast as it goes and the hustle is on and you’re in the hustle—does come out in the ferocity of the line and intensity of color. And living and working in a small Brooklyn studio is as serious as a heart attack and as laughable as a cartoon at the same time.